In the new course I'm rolling out this month (enroll today for access to first-cohort exclusives like great vibes and “Ask Dave Anything” Q&As), I just finished producing a module that has to do with how students remember things.

So, let's look at an inverse of this idea. How do students forget things? Specifically, how do they forget the things that we do in class?

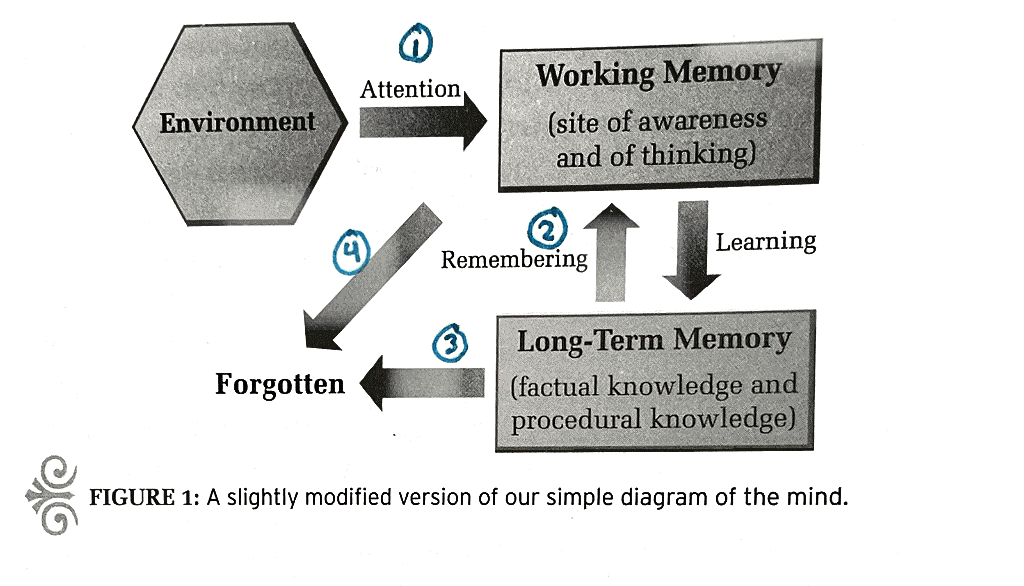

According to Dan Willingham, there are four spots in the human learning system where forgetting can take place.

First, students can forget things we do in class because they weren't attending to them. It's pretty straightforward — you can't remember what you don't pay attention to. As I type this right now, there are a thousand things in my room I could pay attention to:

- An untidy desk (sigh)

- A small pile of articles I'd like to read today

- The whir of the heater

- An aroma from the coffee maker as it does its delicious work

- Jim Burke's planner sitting beside my work computer

- My lesson slide, up on the screen and ready for students

But as I come back to writing this article, those things disappear. They may as well not be here. I'm not experiencing them or thinking about them.

When students are with us in class, there are a thousand things that they can attend to, both within the environment and within themselves. While there's a large-though-finite degree of control you and I have over students' external environment, we have much less control over the internal one. If a student's attention is preoccupied with thoughts of a crush or a hidden cell phone or a frustrating experience in first hour, that student is likely to struggle to remember what we do in class today because what we do has less of a chance to get through the attentional filter.

Second, students can forget things that are in long-term memory due to a failure to retrieve the information. The best way to remedy this is by giving them lots of opportunities to practice retrieving previously learned material. This reminds me of Doug Stark's Mechanics Instruction that Sticks warm-ups curriculum. On each day's warm-up, students begin by writing out the target mechanics knowledge. (See below.)

Regular retrieval practices help avoid situations where students forget because they can't pull what they learned recently from their long-term memory.

Third, students can forget something we did in class because their minds removed it from their long-term memory. In other words — they can forget things because they literally forgot.

I remember back in the old days when, to keep my computer running well, I needed to periodically run a “defragging” program. Basically, when I would run this program, the computer would go through all its bits and bytes, identify fragments left behind by old processes and programs, and either consolidate those fragments or delete them. The mind is exceptionally good at this “defragging” process, especially during sleep.

The solution to this forgetting is making sure students are using and encountering information again and again in class. Some of us teach with curricula that are designed with this need in mind; for the rest of us, we need to make sure we design this kind of repeated exposure into our lessons and instruction.

Finally, the fourth way students forget is when information is forgotten from their working memory. Willingham describes working memory as what you have “in mind” at a given time. As I write right now, all the spaces in my working memory are occupied with this article — what I've already said, the line of reasoning I'm building, ideas from Willingham, ideas from the course I'm rolling out this month, concerns I know teachers like me are likely to have with what I'm saying, and so on.

But let's say that I was being terribly naughty and trying to write this article during a staff meeting. Now truly, I wouldn't do that, because it'd be miserable — I'd be constantly shifting my attention to what the speaker was saying, what the speaker meant for us to be doing, and what I was trying to write. But notice — I would be paying at least some attention.

In this scenario, the reason I'd leave the meeting having almost no recollection of what happened wouldn't be just an attention problem — it would be a working memory problem. Even though I tried paying attention to the PD, my working memory was mostly consumed with the article I was writing. What I had “in mind” during the meeting — what I was thinking about, what I was processing — wasn't the content of the PD, it was the task of writing the article.

And so, I'd forget — because, as Principle 4 in my new course states, “We remember what we think about.”

If you look back up at the Willingham diagram, notice that there's no arrow going from Environment or Attention into long-term memory. Working memory is a key filter — they can't just pay attention, they also have to think.

And it's not just any old thinking that gets the job done well, either — but that's a level of nuance beyond the scope of this article. For a whole module on this concept, consider enrolling in the Principles of Learning Course today.

Best,

DSJR

Leave a Reply