Quick note: Are you interested in a new poster for your classroom this year? I've finally got some for sale, right here. I've even got a Rainbow of Why poster available (here), per common request. Also note that I've made a few mugs for sale (this one will appeal to those of you who appreciate the thinking tools I've shared over the years). Every purchase supports my work — I appreciate you, colleague.

Dear colleague,

At the beginning of my book These 6 Things: How to Focus Your Teaching on What Matters Most, I make an obvious yet oft-neglected argument: teachers suffer for lack of clarity.

- We are not clear on what our classes are for. What's ELA all about? What's science all about? What's physical education all about? We are familiar with what our subject is for, but we're not clear on it. (There's a gaping difference between familiar and clear!)

- We don't respect and care about the fact that our students are not clear on what our classes are for. I'm confident in this observation: I've never met a student who is crystal clear on those questions above. Why am I in an Algebra class right now? What is school for?

- We all suffer for this lack of clarity. Greg McKeown paints this vividly in his book Essentialism: “Clarity of purpose…consistently predicts how people do their jobs….The fact is, motivation and cooperation deteriorate when there is a lack of purpose. If a team does not have clarity…problems fester and multiply. When there is a lack of clarity, people waste time and energy on the trivial many.” McKeown is essentially describing what goes on in most classrooms most days whenever there is a lack of clarity of purpose. The same could be said for most faculty meetings, most PLC meetings, most educational policy statements, and so on.

This sounds a bit dire, right?

As it should. If we don't do anything about this, it is dire. Painful. Frustrating. Exhausting.

But thankfully, there is a solution. That solution is a sentence-long “Everest Statement” about what your class is for.

How to Make an Everest Statement

To begin, simply answer this question by hand: What, in a single sentence, is your class all about? What is a summary of all the work your students will do and what you hope that work amounts to?

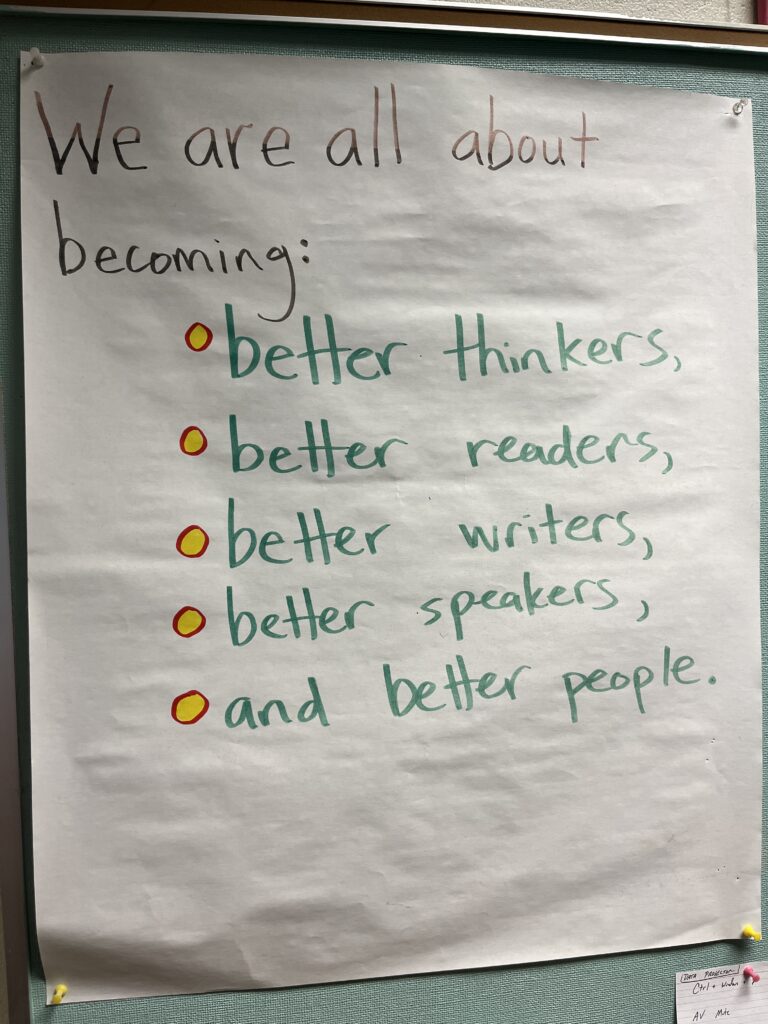

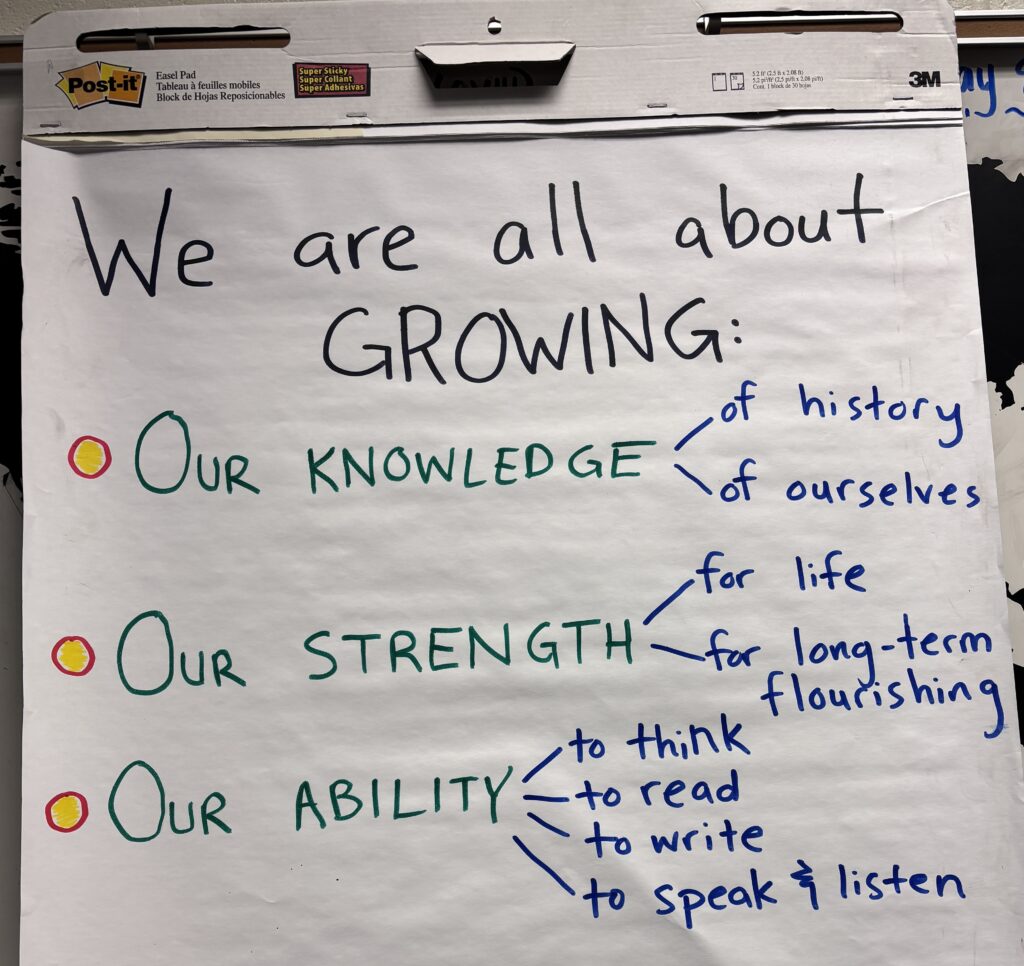

Here is an example from my own classroom:

Here is another one from my classroom, as I was feeling the need for a refresh:

Here is an example from math teacher Caroline Ong:

- Mathematics is all about 1) solving problems 2) in an efficient way, and 3) being able to communicate that problem-solving to others.

Here is one from Spanish teacher Amy Holmes:

- In Spanish, we are all about 1) making an insane amount of errors while 2) trying to make meaning in order to 3) love and 4) understand more people.

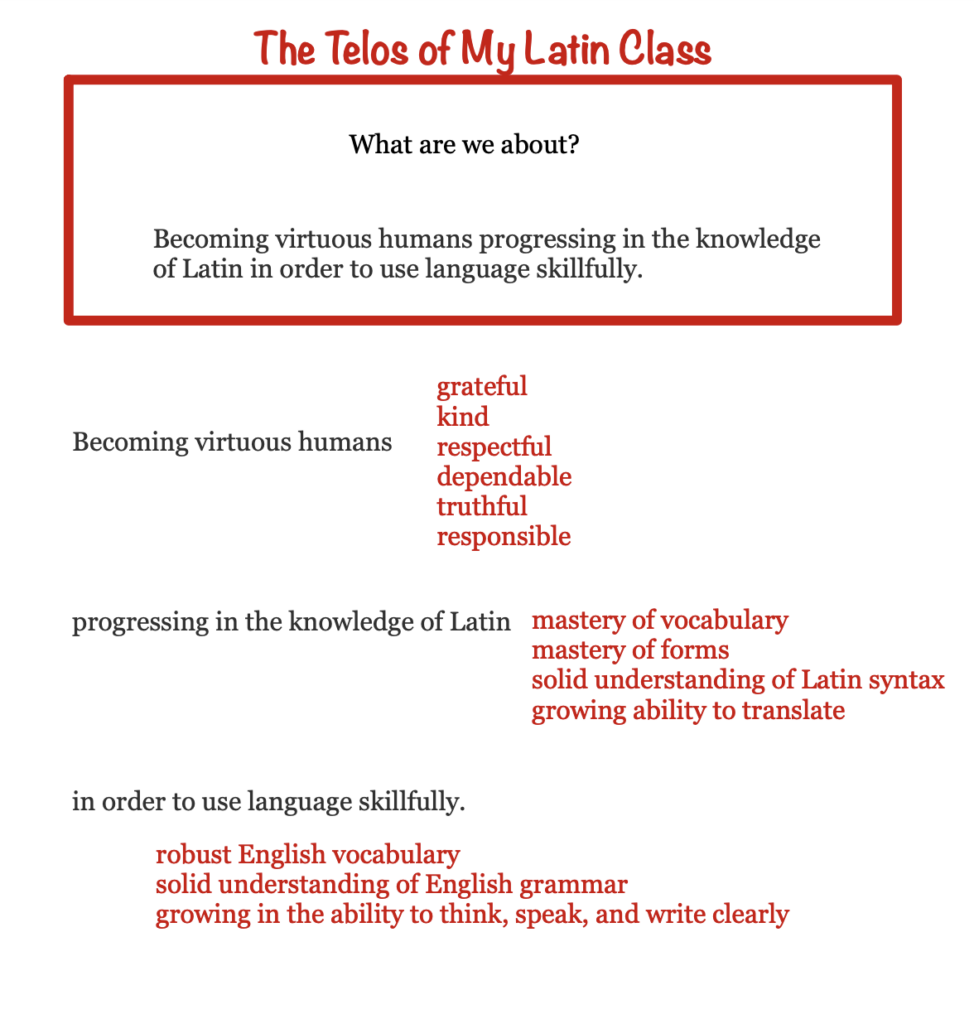

Here is one from Latin teacher Tracey Carrin:

What you're after is a statement that is:

- Applicable to all the learning and work you'll ask your students to do

- Both academic and non-academic

- Resonant with your own teacher's heart

- As short as it can be, but not shorter

Common Problems With Initial Everest Statement Drafts

Over the last decade, I've worked on Everest Statements with thousands of teachers (mostly through the in-person keynotes and workshops I offer). In doing so, I've seen some patterns in the kinds of things teachers initially write that can lead to problems down the line. Here they are:

- An Everest Statement that is too generic: Your Everest Statement should at least strongly imply what subject(s) you are teaching. If you teach multiple subjects, you will probably need multiple Everest Statements. What you don't want is an Everest Statement that could be used by any person who is working with young people. E.g., “We are all about becoming better and kinder people.” Statements like this come from a good place, but they don't solve the clarity of purpose problem we began with. If I'm in a math class, I need more than a statement that says math is about becoming a better and stronger person. How does math class do that? A better example for a math class would be Caroline Ong's statement: Math is all about solving problems efficiently in a way that can be communicated to others. Can Caroline link this with becoming a better and stronger person? Of course — and she does in this brief video. But her Everest Statement is meant to answer the “why” questions students will inevitably have when figuring out the angles and side lengths of triangles — why are we doing this?

- An Everest Statement that is lifeless: Sometimes teachers will be too matter of fact with their Everest Statements. E.g., “In Biology, we are all about completing the lesson objectives as outlined in the standards.” The problem here is that it doesn't help me on the deeper why questions that I have when I'm sitting in your class. Here is another example: “We study economics to uncover the way incentives and scarcity manipulate human and societal behavior in order to maximize productive potential.” This one is not as lifeless as the first, provided that the teacher speaks life in to it when he uses it during instruction.

This latter problem gets us to the more important and difficult matter of how to use an Everest Statement to its greatest effect.

- For more on creating an Everest Statement as an individual, see this article.

- For more on creating an Everest Statement as a department or PLC, see this article.

How to Use an Everest Statement

Like any teaching tool, Everest Statements act as a multiplier of the skill with which the teacher uses them. If I simply write down my sentence on chart paper and affix it to my wall, I'll see no noticeable impact on my clarity of purpose or on that of my students.

Here are some simple ways that an Everest Statement can be used effectively.

- Start of the year: On the first day of school, it's helpful to introduce your students to your Everest Statement. Keep it brief, dose it with quiet passion, and move on with the first-day-of-school agenda. It's the first of many times you'll define big-picture success for your students using your Everest Statement.

- Reducing your teacher guilt: Some days, the work is frustrating. You created good lessons, but they didn't go well. Things were off. Lesson chunks that were meant to take five minutes took fifteen; chunks that were meant to take fifteen fizzled out after five. On days like these, I can start to get down on myself, wondering if I really know how to do my job at all. On days like these, I can look at my Everest Statement and ask myself, “Did we attempt to do any of this work today?” If my answer is yes, I can give myself permission to go home and try again tomorrow. I can remind myself that ascending Everest is hard; sometimes, the weather doesn't cooperate. That's all part of teaching. My job is to help my students toward becoming better thinkers, readers, writers, speakers, and people. If I attempted to do that today, I can rest even if it all went poorly. I can use the failure to teach me more about how to do this work well. And I can try again tomorrow.

- Mini-Sermons: In The Will to Learn, I unpack the 10 strategies that yield the best results in cultivating student motivation over time. One of these strategies is the Mini-Sermon, in which I briefly (in 30-60 seconds) explain to my students why what we're working on has Value. Everest Statements help form the foundation for these mini-sermons.

- For more on mini-sermons, see Strategy #4 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR Guide I created for the strategy.

- Clearing the clouds: The thing with high peaks is they are often obstructed by clouds. When working with students, I've learned that they need me to help clear those clouds on a regular basis. When I'm sensing that students aren't clear on the why of an instructional activity, I can use my Everest Statement to communicate to them what we're doing this for.

- For more treatment of this idea of cloud clearing, see this article.

- Selecting instructional activities: Students have a right to never experience busy work — work designed for the purpose of “keeping students busy” versus work designed to help them grow toward Everest. In the video below, I give a few examples of how my Everest Statement helps me select instructional activities that congrue with what my class is all about.

- Making adjustments as the school year progresses: Climbing mountains is hard work, so I'm told. Everest Statements help us head in the right direction, but they also help us make adjustments as the year unfolds.

- For more on this idea of making adjustments en route to Everest, see this article.

In Sum: A Five-Minute Mini-Keynote on Everest Statements

Here is a brief talk I gave at the National Council of Teachers of English conference in 2016. You might be thinking, “Well, that's outdated.” But it's age actually proves my point: I still use this tool, to greater effect now than I was capable of then.

So there you have it, colleague. A simple, critical, foundational tool. It helps me. It helps my students. It's fundamental.

Let me know how it goes in your classroom.

Teaching right beside you,

DSJR

Holly says

Hey Dave! Been working on my Biology Everest Statement since the workshop in St. Clair, Illinois! Here goes:

Biology is to figure out us and the world we live in; helping to shape us into intelligent-reading-writing-communicating-questioning-critically thinking-evaluating types of literature and opinions from various people and places, kind of kids and maybe finding an unexpected passion for a branch of science we had no clue existed.

Whew! I’m not sure my grammar is correct and how well it flows but this is better than my first draft. Is this clear enough?