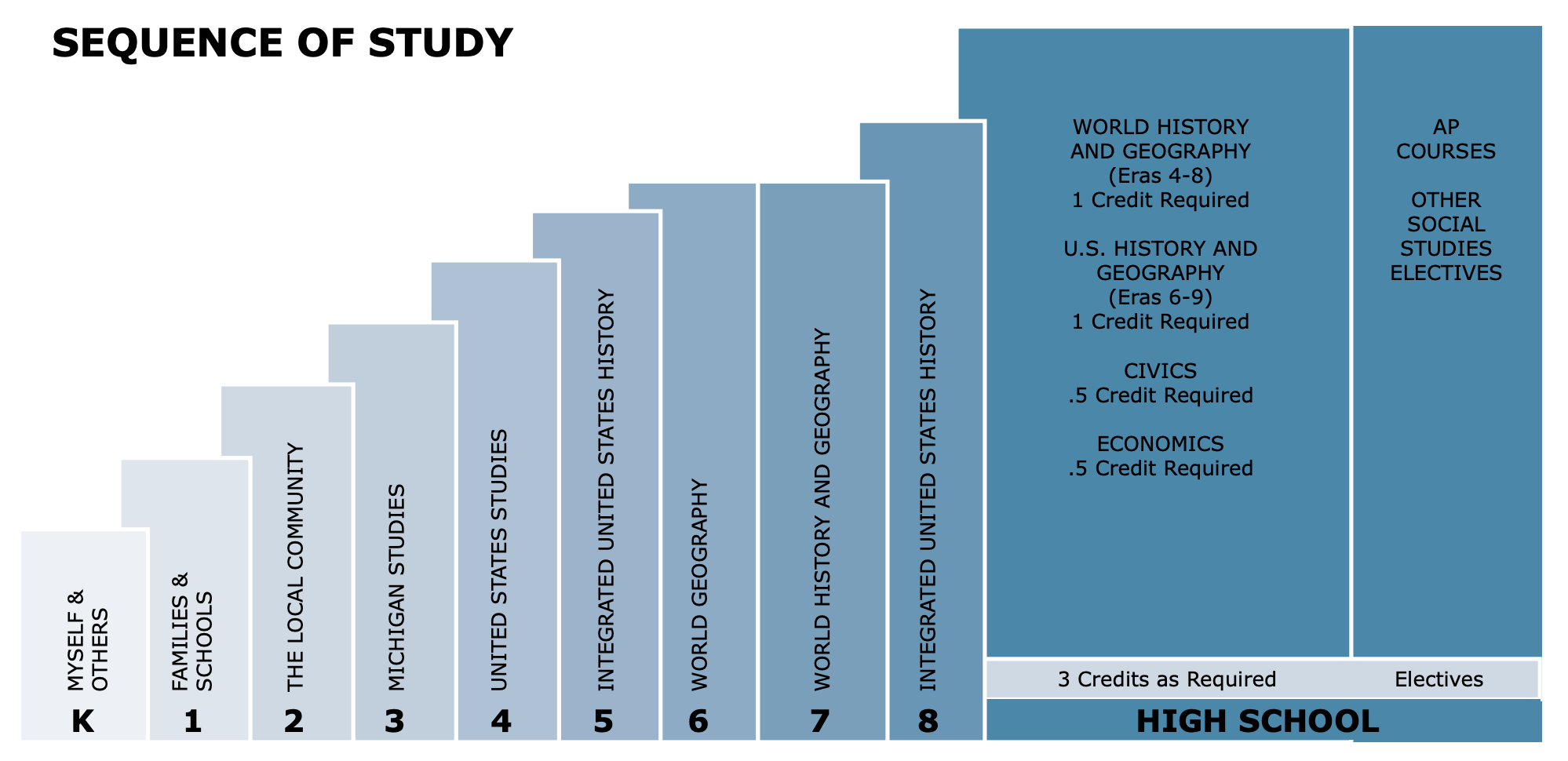

In the state where I work, the social studies standards call for the following grade-level emphases:

- Kindergarten: Myself and others

- Grade 1: Families and Schools

- Grade 2: The Local Community

- Grade 3: Michigan Studies

- Grade 4: United States Studies

- Grade 5: Integrated United States History

- Grade 6: World Geography

- Grade 7: World History and Geography

- Grade 8: Integrated United States History

This “expanding horizons” model — start with the self and build outwards — is the most common approach to social studies in the United States. Sadly, it is built on a broken hypothesis: that our youngest children aren’t interested in, or are somehow developmentally unable to understand, subjects like history and geography. As they grow, the theory goes, their minds become more able to grasp the timelines of history and the different places in which history takes place. Also, the older mind is more interested in these “bigger than self” things.

Sadly, the truth is exactly opposite.

Young children are curious to learn as much about the world as we’re willing to teach them, and they are remarkably able to do so. Their minds ignite at the chance to listen to stories from ancient Mesopotamia and classical China; if given the chance, they will clamor for descriptions of the Mongolian empire and the travels of Marco Polo; if taught the biographies of people like Mansa Musa and Marie Curie, they’ll start pretending to be them at recess. I see this sprinkled in the research (and most recently, in Natalie Wexler’s excellent The Knowledge Gap: The Hidden Cause of America’s Broken Education System—and How to Fix It) and lived in front of me in my own children.

Ask my fourth grader Hadassah or my second grader Laura or my first grader Marlena some abstract question about themselves and others, and you’ll see their pulses slow. On the other hand, tell them it’s time to learn more about the Vikings or about the solar system, or that you’ll take them for a walk at the local park to find and classify different kinds of plants and bugs, and their eyes will brighten.

Now granted, my children are probably weird because they are my children. But this particular instance isn’t because of their weirdness — it’s because they are children.

Our youngest children are desperately eager for an education rich in things: in physics, in biology, in astronomy; in history, in geography, in people. And yet what we give them, per most of our states’ standards, are generic lessons on “social studies,” very often tacked at the exhausted ends of a demanding elementary school day.

If you’re for equity, then it’s time to be against this. If you’d like to diminish the achievement gap in your school and raise the horizons of all of your students, read Wexler — and start changing things now. No need to disregard your state’s requirements, either — you can teach “myself and others” along the way without a bit of trouble.

It’s actually in adolescence that the human mind turns inward, newly concerned with its identity and its place in the social world. That “myself and others” kindergarten unit? It probably fits best as a theme of seventh grade. The trouble is, if you’ve neglected to provide a curriculum rich in things for the K-6ers, then now you’ve got a problem: that adolescent mind isn’t as eager to learn stuff just to learn stuff. It’s interested in what it already knows — which, thanks to pervasive myths supporting knowledge-lite elementary curricula, is far less than it could.

I find it unlikely that state social studies curricula like mine will any time soon reflect what cognitive science has been indicating for over a decade: critical thinking, reading comprehension, and even the ability to learn hinge on the things the brain has learned.

And our youngsters are eager to learn things.

So, it’s time to rethink the practice of saving social studies and science for the end of the elementary school day, and it’s time to rethink the expanding horizons model for social studies education, and it’s time to rethink the idea that knowledge of the content areas isn’t mission-critical for literacy outcomes for all children.

Barbara Paciotti says

Thank you, Dave, for bringing this some much-needed attention. I think the big problem is not the model, so much as how it is applied. The original point was to align curriculum with the cognitive abilities of students, but that has been grossly misapplied, as you so effectively point out, as the interests of students. We can effectively teach a wide range of content material–even global awareness–if we keep the thinking ability of kids in mind.