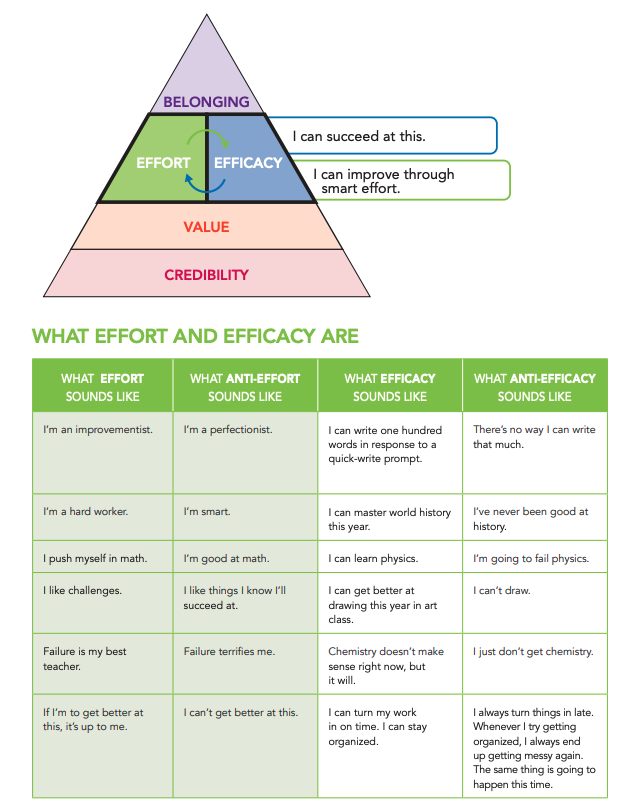

The Effort and Efficacy beliefs form the third layer of the Five Key Beliefs of student motivation, which I unpack at length in The Will to Learn: How to Cultivate Student Motivation Without Losing Your Own and in Chapter 2 of These 6 Things: How to Focus Your Teaching on What Matters Most.

What are the Effort and Efficacy beliefs?

Let’s begin with Effort. The most helpful avenue to help you interpret the Effort belief effectively is to talk about ways in which students misunderstand the role of Effort in improvement.

The Effort belief is absent when you don’t think you can improve.

Here we’re talking about two kinds of students:

- Those who think they’re just “not a math person”—as if no amount of Effort can improve the degree to which they achieve or fail in math

- Those who think they’re math geniuses—as if something inborn in them is the reason they are so good at math versus a trail of experiences in their lives in which they’ve undergone growth in mathematics.

It’s this second kind of student that we often overlook. Because they tend to get A's in the grade book or perfect scores on tests, we presume they are adequately motivated. But when a student thinks Effort is something detached from their ability to improve, make no mistake: that is a student inflicted with Effort unbelief.

Stanford’s Carol Dweck calls this Effort unbelief a “false growth mindset.” According to Dweck, who popularized her career’s research with the book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, false growth mindset is something all of us struggle with, especially in circumstances where we:

- Are asked to work outside of our comfort zones

- Meet someone who is much better than us at something we previously thought we were very good at

- Hit an obstacle that appears larger than our current ability to overcome it

So the Effort belief is critical when students experience the kinds of challenges that best promote growth toward mastery.

(Note that in Dweck’s terminology, what I call the Effort belief is the same thing as what she calls growth mindset or, in her more technical writing, an incremental theory of intelligence. As I explain in The Will to Learn, I find the term belief to be a more straightforward way to describe what Dweck and her colleagues are after with the term mindset. Being a psychologist, Dweck’s work is rooted in the world of the mind, but being just an ordinary teacher, I can deal with human beings in a more holistic, whole-soul sense.)

And now we move to Efficacy. When a student encounters a growth-supportive challenge that seems bigger than their ability level, an internal check occurs: Can I do this? Will I come out on top? Can I succeed? It’s like the sign before the rollercoaster line that asks, “Are you tall enough to ride this ride?” It’s hard to overstate how powerfully our beliefs about our Efficacy predict our performance.

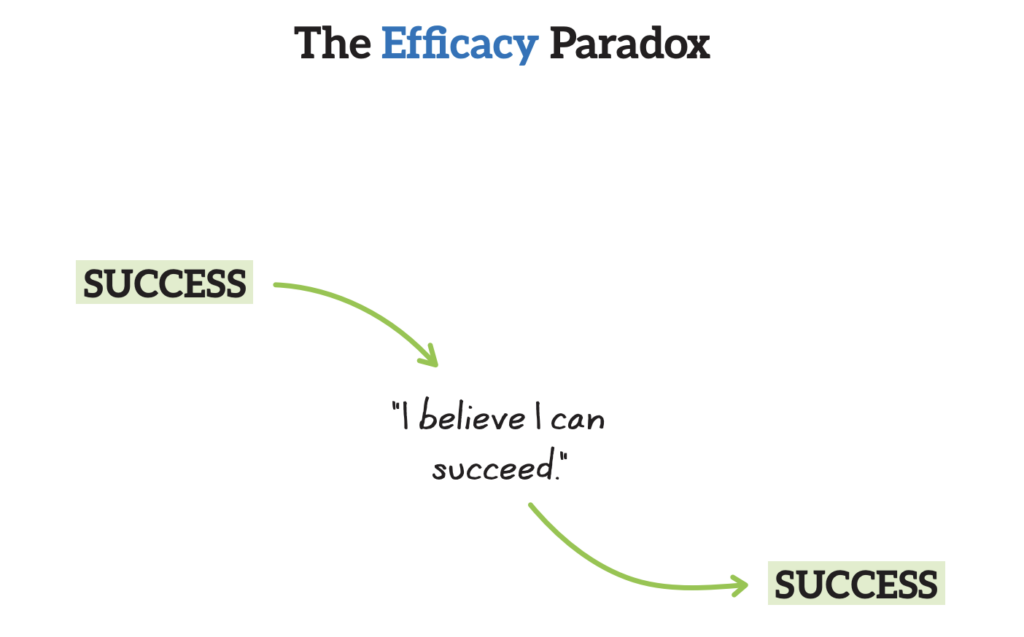

The best way to help students believe in their Efficacy is, of course, to help them succeed at hard things. The proof, as they say, is in the pudding. When students succeed, they believe in their Efficacy; when they believe in their Efficacy, they are more likely to succeed. It’s a bit of a chicken-or-egg paradox.

In the front of my classroom hangs a sign that says, “Do hard things.” I hang it there to remind both my students and myself that the things we do are difficult yet attainable.

But if all I did was display that poster, it wouldn’t do much for my students’ Efficacy. Ultimately, for Efficacy to develop, a student must succeed. This is why it’s so important to teach students the steps to success for anything hard you’re asking them to do (see Strategy 7 in The Will to Learn or this guide on Woodenization), to define success in a manner that’s attainable yet attractive for all students (see Strategy 8 in The Will to Learn or this guide), and to unpack outcomes both good and bad so as to help students understand where success or failure comes from (see Strategy 9 in The Will to Learn or this guide).

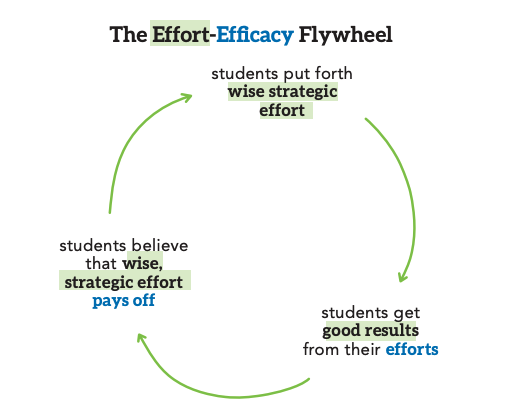

Now, having examined Effort and Efficacy separately, let’s see how they play together. In the Five Key Beliefs model I’ve explained in this guide, Effort and Efficacy circle one another. The reason for this is something that I call the Effort-Efficacy Flywheel. Basically, the Effort and Efficacy beliefs feed into one another and, over time, can create a virtuous cycle. Like in an actual flywheel, momentum in these two beliefs breeds their further momentum.

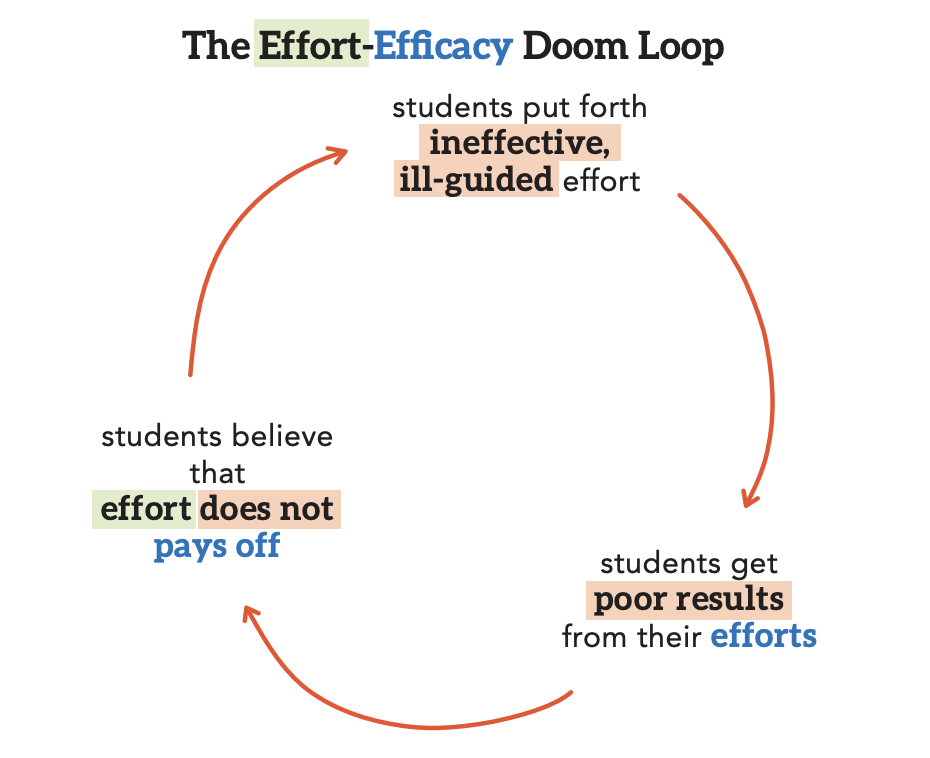

Alternatively, of course, an inverse cycle can occur—we can call this the Effort-Efficacy Doom Loop.

All we need to do for Effort and Efficacy, then, is to remedy those spots in the loop that allow room for doom and strengthen them in order to create a virtuous, self-empowering flywheel. This is what the Will to Learn strategies below help us achieve.

How can I cultivate the Effort and Efficacy beliefs in my classroom?

At the end of this section, you'll see a list of articles I've written over the years sharing many ways you can cultivate the Effort and Efficacy beliefs in your students. But when I wrote The Will to Learn, I was determined to identify the fewest, biggest-bang-for-your-buck strategies I could. I narrowed and narrowed and narrowed, until finally I had arrived at three core strategies for cultivating Effort and Efficacy.

- Strategy 7: Woodenize All of It. In this strategy, we seek to effectively teach, model, and reinforce every learning-conducive behavior that we expect of our students. The strategy is named after legendary UCLA basketball coach John Wooden, who famously began each basketball season by teaching his players how to put on their socks and shoes. This strategy is all about making effective effort clear for all of our students.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 175-193 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR Guide.

- Strategy 8: Define Success Wisely, Early, and Often. Most students do not have a clear or helpful idea of what success in school looks like. In this strategy, we seek to communicate our vision of success to students and help our students generate and reflect upon their own definitions of success.

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 194-205 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR Guide.

- Strategy 9: Unpack Outcomes, Good or Bad. This strategy is all about pointing our students' attention toward wisely interpreting how their learning is going. If we don't do this, students are likely to make maladaptive interpretations of both bad results (e.g., “I did bad on the test; I'm stupid”) and good results (e.g., “I did good on the test; I'm smart”).

- For a detailed treatment of this strategy, see pp. 206-218 in The Will to Learn or this DSJR Guide.

Extra “Booster” Strategies for the Effort and Efficacy Beliefs

Outside of the core strategies outlined above, here is a list I'll keep updating of brief articles I've written to describe more Effort and Efficacy boosters.

- Eight Lessons for Enhancing the Effort and Efficacy Beliefs

- The Effort Belief in Action: Read Naturally as a Case Study

- End of Year Efficacy Booster: Unpacking Outcomes via Conversation Challenge

- Efficacy and the Brain 101 – David Reese Guest Post

- Booker T. Washington on the Efficacy Belief

Common Questions and Hang-Ups About the Effort and Efficacy Beliefs

Oh, I've heard about growth mindset. Yeah, I'm a growth mindset person.

There are two reasons I use the term Effort belief rather than growth mindset:

- Mindset is an unhelpful word to me. It gives too little acknowledgment to the human heart, will, and soul. We’re not just minds.

- Growth mindset is a term that everyone has heard of but only a small sliver understands.

(To that second point: In one study, over three-quarters of teachers indicated that they were very familiar with growth mindset.)

Let me explain that last claim. When her book was rocking the bestseller lists in the early 2010s, Carol Dweck started to notice a problem: Folks were speaking about growth mindset in ways that had no grounding in her research.

For one thing, Dweck noticed folks were discussing growth mindset as something you either have or you don’t—more like an on/off switch in the head rather than a fluid belief that slides along a spectrum. “You hear a lot of people saying, ‘I’m a growth mindset person’,” Dweck said in an interview, but “it turns out that we’re all a mixture, often depending on the environment we’re in.” Consider, she said, what happens to you when you encounter someone who is way better than you at something that you consider yourself good at: You experience doubt; your belief shifts. In other words, the Effort belief, like the rest of the Five Key Beliefs, is context-dependent (as I've explained more in this guide and Chapter 2 of The Will to Learn).

Another misunderstanding with growth mindset is that to develop it in children, you must never call a child smart and you must always praise the process rather than the person. These maxims are drawn from sound research—for example, study participants have been found to succeed less when they’re told they’re smart in a given area versus when they're told they work hard in a given area—but they oversimplify the complex process of belief formation in a human soul.

Let’s say you have a student who has worked very hard on a lab report in his science class, but the lab report is very bad. In this case, praising the process would be nonsensical—after all, the process did not work. Valorizing ineffective Effort sends a signal to students that school is a bizarre place where outcomes don’t matter—all that matters is that you try. While such a world would perhaps have its perks, secondary students are savvy enough to know that in other domains of life—sports, clubs, chores, jobs—it’s not just effort that matters. Outcomes matter, too.

All of which is to say that I recommend you clear your mind of what you think you know about growth mindset before moving further into your work with the Effort and Efficacy beliefs.

Think only of this:

- How am I demonstrating for students that effective Effort can pay off?

- How am I making effective Effort clear?

- How am I designing challenges so that they are attainable to my students but also challenging across the wide spectrum of my students’ ability levels?

Not easy questions, are they? Yet they are critical.

My students won’t do anything.

When you have a student who refuses to do anything, you must first depersonalize the situation, and then ask yourself a few targeted questions.

First of all, remember: What happens in our classrooms isn’t about our internal worth. We can’t take demotivation personally. It serves no good end. That established, here are a few questions to ask yourself:

- Have I made the work clear? Have I broken the work down into its smallest chunks? Woodenization helps with this (see Strategy 7 in The Will to Learn or this guide).

- Have I demonstrated to students that I care about them, academically and personally? Moments of Genuine Connection (MGCs) will help with this (see Strategy 1 in The Will to Learn or this guide).

- Have I sought to winsomely and confidently “make the case” for this work? Mini-sermons will help with this (see Strategy 4 in The Will to Learn or this guide).

- Is the work appropriately challenging for this student? Not too easy and not too hard? If it’s not appropriately challenging, what are the simplest means through which I could remedy this?

Through it all, keep this one idea in mind: All human beings want to be motivated. This student does, too. There’s just something getting in the way right now—something that you get to work at puzzling out.

My students are working hard, but their work isn't paying off.

A student walks up to you and says, “Ms. Smith, I don’t get it!” There are tears in her eyes. “I studied for five hours last night, and then today on the test I still failed it. Argh!”

This is such an important situation that I've got a whole strategy that deals with it: Unpack Outcomes, Good or Bad (see Strategy 9 in The Will to Learn or this guide).

Still got questions?

If you ask a question in the comments section below, I'll answer it and incorporate your question into this article. In other words, you'll get a double whammy: You get your question answered, and you help make this article better for future readers.

Teaching right beside you,

DSJR

Leave a Reply