Dear colleagues: David Reese, the author of this *super rare* guest post on the DSJ blog, is a long-time correspondent, colleague, and friend. And he'd be your friend, too, if you met him. Loving, kind, smart, passionate — DTR is all of the things. And so today, I want to let him share with you how he teaches his high school English students about Efficacy and the Brain.

DTR, take it away.

My name is David, and I’m a high school English teacher. If I had to name just one thing that makes me qualified to teach ELA, it is the fact that I hated reading when I was a kid. I read just one book cover-to-cover in all of middle school and high school. It was a dog book. At some point in high school I realized, Why read this whole book when I can just fake it and get good-ish grades? And since no one held me accountable for this garbage approach to school, it became my default setting. Therefore, I learned next to nothing in four years of ELA, and it felt like a complete waste of time.

All this changed in college. Now, I’m kind of on fire with wonder and learning—which feels really good. (<–This sentence is kind of a big deal because educational neuroscientist Richard Davidson says that learning and emotions are enmeshed. Like it or not, we can’t separate emotions from learning. So why not leverage that neurological fact?) A few years ago I decided to lean in to this phenomenon by being more explicit about the connection between learning and emotions. And this isn’t hard because everyone knows it in their bones already. I mean, we like it when we know more stuff about our favorite topic.

That feels good.

We like (<–emotion) knowing stuff (<–learning).

Now here is an important flow-chart of sorts:

- Learning and emotions are enmeshed.

- Time is precious.

- If I want my curriculum to matter (because time is precious), I need to make it count.

- If I want to make it count, it better have value,

- And it’s not enough for me to see the value of the curriculum. The students need to see the value.

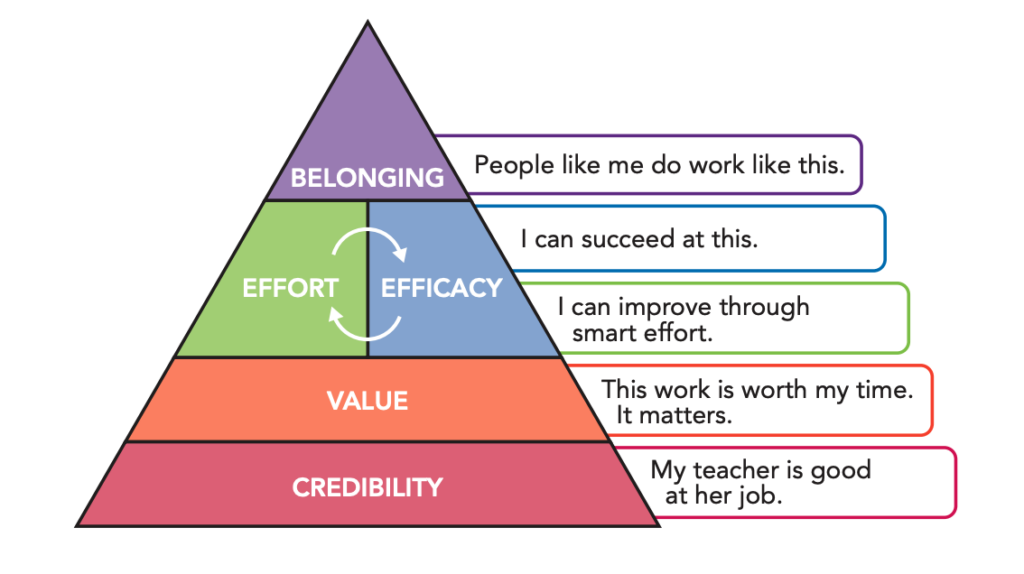

If you are reading this on Dave Stuart Jr’s blog, then like me, you have discovered the value of the 5 Key Beliefs.

For the past few years I’ve been thinking more and more about them. And man, if there was just ONE THING I’d like my students to know, it's that they have agency. That they possess Efficacy. That it’s within them to shape the outcome!

But to really know this, you have to know it in your bones, not your head. In essence, this requires a type of experiential learning. But experiential learning about what? How about something concrete? Like, what it means to be human?

That seems worthwhile.

That seems relevant.

That seems Valuable.

Here are two bits of wisdom I want my students to know:

- They possess agency/efficacy (somewhat abstract wisdom).

- They know some stuff about the human brain, which explains why we do some of the things we do (a bit more concrete wisdom).

A week or two into the beginning of the school year, we start with a unit I informally call BRAIN 101. This starts with students memorizing some important information about the brain. Why? Because a certain amount of brain science, or neuropsychology, helps explain why we do some of what we do. Plus, it totally connects to all kinds of texts we study later on, which range from New York Times articles about sleep to satire like “The Substitute Teacher” from Key & Peele. (Yes, we actually analyze a few sketches from Key & Peele. At the bottom of this blog post you will find a sample paragraph that one of my ninth graders wrote.)

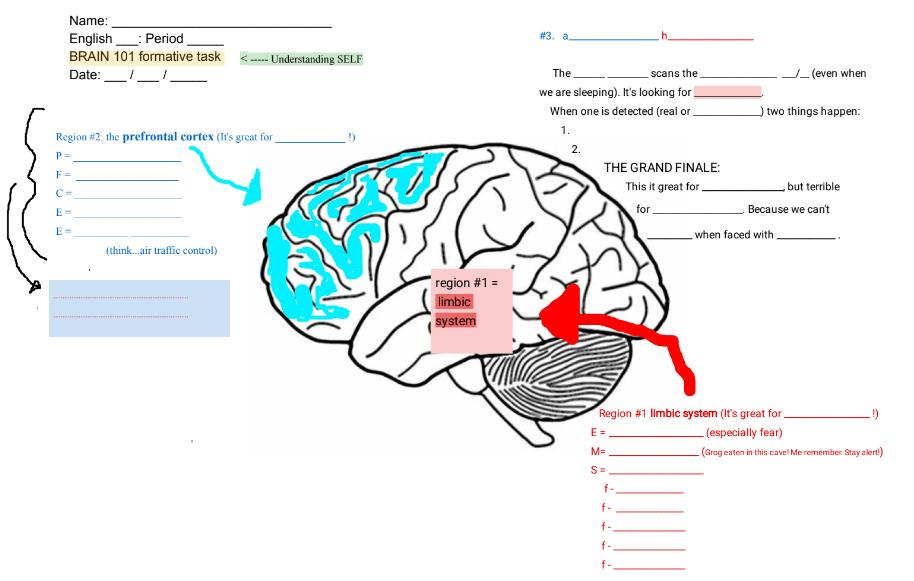

BRAIN 101 requires students to know about two crucial regions of the brain (the limbic system and prefrontal cortex) and the phenomenon we call amygdala hijack.

After twenty years of teaching, I’ve finally learned that if I want my students to know certain stuff, I need to make the stuff accessible. Here’s how I attempt to make it accessible.

Step 1: I provide skeleton notes.

I use a document camera and/or smart board to project the skeletal notes. Then, over the course of a couple of class periods, students fill in the blanks on their piece of paper. (DSJ said he would buy a coffee for the first 5 teachers who prove they use overhead projectors. #ifitaintbroke) I tell the students that, in time, they will need to memorize everything on this piece of paper. Aaron’s notes are below:

Step 2: Helpful acronyms and memory tricks.

BRAIN 101 starts with information about the limbic system. I help the students memorize key information about these two regions with a few memory gimmicks and acronyms.

- The limbic system’s favorite song is “Stayin' Alive” by Bee Gees.

- What follows is an appropriate acronym:

- E = Emotions (especially fear)

- M = Memory (Grog was killed in a cave like this, I better be alert.)

- S = Survival (which has 5 sub components)

- F – freeze

- F – flea/flight

- F – fight

- F – food

- F – fornicate (sex drive)

Region number two is the prefrontal cortex. We refer to it as our learning brain. The prefrontal cortex has a built-in acronym: PFCEEx.

- Its favorite song might be “I Wanna Get Better” by Bleachers. (I welcome better, more effective song suggestions. Superior suggestions will win a coffee from DSJ.)

- PFCEEx

- P = Planning

- F = Focus

- C = Control (self-control)

- E = Empathy

- Ex = Executive function

Key phenomenon: amygdala hijack.

I don’t have an easy acronym for amygdala hijack. As a result, committing all its details to memory requires some old school memorization. Which leads us to our next point:

How do we make all this stick?

Repetition.

The one phrase I probably repeat the most over the school year is this: “Like most everything, …….blank…. is a muscle! It gets stronger with reps and effort.” (I’ve recently come to embrace the value of repetition. We intuitively know its worth. We know that the more we lift weights, the stronger we get. It’s the same with reading, with writing, with forgiveness, with focus, with compassion, with memory, and with writing a 250+ word response to this week’s article of the week.)

Over the course of a few weeks, we do a number of “throw-away” quizzes (non-graded, non-submitted) as well as more formal quizzes (which I assess).

Taking a somewhat challenging quiz (or test) multiple times provides us with the opportunity to track our progress. And this is where AGENCY, or EFFICACY, comes into play.

Anything we do multiple times allows us to ILLUSTRATE two key beliefs: efficacy and effort. And I don’t need to get high tech. Here. Checkout what Aaron has in his spiral notebook:

As you can see, Aaron has taken the BRAIN 101 quiz three times (not counting the various throw-away quizzes). On Sept 14th he scored a 3.6 (D-); on Sept 21st a 4.25 (D+). After taking the quiz twice, students: A) made a bar graph in their notebook, B) wrote a comment about their first two scores, then C) wrote a definition of the word efficacy. The following week students set a goal for quiz #3 then had 10 minutes to study for the quiz. As you can see, AA Ron’s goal for attempt #3 was a 4.5 (C) but he actually scored a 6 (A). Aaron knows that if he scores a 6 (A) on the next BRAIN 101 quiz, he won’t have to do it again because he will have “mastered” this knowledge.

As I continue to read and reread Dave Stuart Jr’s work on effort and efficacy, I’m seeing just how magical moments like this can be. That’s why this year I’m being super explicit about efficacy and effort.

Like I mentioned before, I want students to KNOW that they possess agency. That they have efficacy. That they possess the ability to have an effect on an outcome. I can help students discover this wisdom by referencing these very quizzes. The iron is hot for striking!

In an effort to really spell things out, I created a simple google document, which sort of forces the student to reflect on their work. Here are two examples (yes, I changed the names):

I find the students' comments fascinating. Quite a few wrote things like, “I was surprised to see my score go up so much just from studying for a few minutes.” The pessimist in me might see this comment and say, “No duh,” but the optimist in me shouts, “Look at this!!! Here is a student realizing, in almost real time, that studying has an effect!!!!” Now, it’s not all good news. If you take a look at Jay’s response to #4 you can see that I still need to help them develop an understanding of efficacy. They wrote, “But I didn’t have enough of efficacy because I forgot to study sometimes.” I need to show them that when they did study, when they were “focused,” they did well—in fact, better than they projected, which is precisely what efficacy is.

I love what’s happening here because we are creating an anchor experience that we can refer to all year long. We can reference this moment as a lived experience, which illustrates not only the power of efficacy, but the positive emotions that come along with knowing that I can have some effect on the outcome. And now that I know this, I can leverage it if and when I want.

Final note:

This entire blog post pertains to my standard 9th grade ELA class. I’m tempted to write a parallel one about my advanced 9th grade ELA students who just memorized a full sonnet. They struggle for a while, then feel great when they can successfully recite all 14 lines to their classmates.

STUDENT SAMPLE PARAGRAPH illustrating amygdala hijack in the satirical comedy sketch “Substitute Teacher” from Key & Peele:

Missy Dunn says

Excellent topic today!! And so true–my day is filled with comments about how they don’t care about____ and it’s boring, etc. We’d rarely hear that if they felt good (or at least decent) about the subject area, even if it’s challenging.

Ryan Hubbard says

Great post!

Too many of our students have lost their belief in agency or efficacy through repeated failure in school. Giving these students early opportunities to experience moments where their effort pays off is crucial. Pointing out the growth and asking them to reflect on the process will help germinate that seed of belief again and allow further cultivation in later activities.

Tammy Tow says

I am trying to read Aaron’s notes. What is the word for the blank: “The limbic system scans the ????? 24/7 (even when we are sleeping.)