Over the summer, my Advanced Placement World History students are assigned to learn a set of dates and what those dates mean. That assignment has evolved (and simplified) with each year I've given it, but it's purpose is always the same: I want my students to have an initial, very rough draft of world history sketched out in their minds before the first day.

Over the summer, my Advanced Placement World History students are assigned to learn a set of dates and what those dates mean. That assignment has evolved (and simplified) with each year I've given it, but it's purpose is always the same: I want my students to have an initial, very rough draft of world history sketched out in their minds before the first day.

In my standard world history courses (which I design to require more reading and writing and arguing and knowledge-building than what the curriculum calls for; after all, it's more fun to do hard things), I don't have the luxury of the summer assignment, and so the first unit of the school year is seeks to tie material learned from middle school with a rough draft overview of what we'll learn this year.

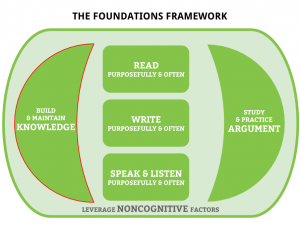

From September to spring break, in all of my classes, we create the second draft. For this one, they've got me as their teacher, they've got each other, and there will be lots of reading, writing, speaking/listening, and arguing as we go about the business of learning what Ben Freeman calls “the history of everything that's ever happened, ever.”

After spring break, we spend our final weeks of the school year (before the AP exam for the AP kids, before semester exams for the kids in the standard course) creating a third (and final, for our year together) draft of world history. Once again, we go through the material — this time through reading SparkNotes-style summaries of each of the major periods, through listening to and taking notes on my abbreviated interactive lectures on each period, through writing summaries of each period, and through crafting several kinds of argumentative essays (specifically, we do essays on causation, change and continuity over time, comparison, and periodization; this is the part of the year where my stopwatch gets handy). This third draft culminates in a self-directed research project towards independently generated questions — and the process of completing that project yields an additional fourth draft of learning on whichever question the student has chosen to pursue.

This is the flow through which I seek to help my students build and maintain knowledge in a world history course. It is, of course, a work in progress, but I'm seeing my students get further — in their knowledge, in their ability to think, read, write, speak — through this recursive, “drafts of learning” approach than I used to through a more traditional, one-time-through method.

I didn't happen on this thinking out of nowhere, of course. Here are some like ideas:

- Kelly Gallagher writes about second- and third-draft readings of novels in Deeper Reading.

- The CCSS address the recursive nature of grammar and mechanics in their language skills progression chart. (Notice how subjects and verbs are taught not just at Grade 3, but all the way up to Grade 12. This is because sentence complexity in Grade 3 is quite different from sentence complexity in Grade 12. The knowledge gained in the lower grades needs refreshing and refining in the higher grades. Secondary ELA teachers, take note!)

- Doug Stark spirals the language knowledge taught in his Level A Mechanics Instruction that Sticks book into his Levels B and C books.

So here's the question: Is there a way that the material in your course could benefit from a “drafts” approach to learning?

Brad says

Dave, love your thinking here. Love how it really asks students to revisit content from earlier in the year. An awesome way of progress monitoring and encouraging the growth mindset by showing how much knowledge and thinking have grown over the year. Would love to see actual examples of what this ends up looking like.

davestuartjr says

Brad, I’d love to make those actual examples — it’s on the to-do list!

dkenley says

Good morning, Mr. Stuart,

I enjoyed today’s post…it makes a lot of sense. I am a site administrator and I plan on sharing your thoughts with our teachers.

Wondering…would you be willing to share your syllabi for both World History courses?

Thank you in advance for considering my request and for your thought provking blog!

Dan Kenley

dkenley13@gmail.com

davestuartjr says

Dan (and Lynn), this post is abstract because it’s a pretty rough draft idea in my own mind. The “drafts” I’m referring to aren’t pieces of writing — they are learning experiences. At the start of the year, we learn geographic locations and a list of dates, with very little information to tack onto them; as we progress through our year’s units, we add flesh onto these dates through ample reading, writing, speaking, arguing, and knowledge-building. And at the end of the year, we revisit all that we’ve learned and push to deepen understanding and transfer to issues facing today’s world.

I don’t have exhaustive syllabi, unfortunately — they simple list my units (e.g., Unit 3: Post-Classical Era, 600-1450 CE), my grading policy, and other mundane information.

Lynn K. says

I find your ideas here intriguing, but unlike most of your blog posts, a little too abstract for me to immediately understand. Usually, I can take what you write about and think of ways I can apply your ideas to my classroom teaching. I guess I don’t really understand how you are using the word “draft” here. Are your students actually writing a draft of their concepts of world history, and then revising it 2 or 3 times? Maybe you can explain more fully? Sure hope yuh can take some time to do this. Thanks!

davestuartjr says

See above — I wish I had more for you, my colleagues!

ImpassionedEducation says

I agree with Lynn. I’d love to see your directions to students for the first draft assignment.