Critical thinking is a problematically over-extended term. It's sort of like close reading — we can all agree we want kids to be great at it, but if you put ten random educators in a room and have them each write down their clearest, most actionable definition of close reading, you'd get a wide range of meaning.

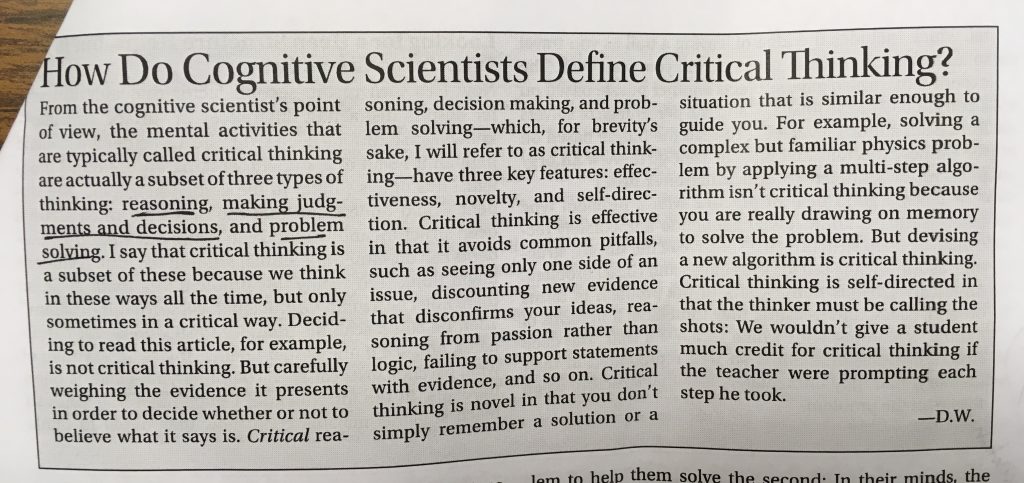

Daniel Willingham, a cognitive scientist who has written extensively on education, says that cognitive science sees critical thinking as “a subset of three types of thinking: reasoning, making judgments and decisions, and problem-solving.” [1] In calling critical thinking a subset of these, he means that even though we frequently reason, make decisions and judgments, and solve problems, these aren't always done in a critical manner. For a full treatment of his definition of critical thinking, see Figure 1.

The trouble here is that, even though Willingham's treatment of the term is the clearest, most robust, and most concise that I've seen, I still feel overwhelmed by it. The central thrust of Willingham's whole article is, indeed, that teaching critical thinking is difficult for several important reasons. I see the Willingham definition and read his article, and I think, “Okay — someday I'd like to have my head fully wrapped around that and to have a solid plan for attending to it in all of my courses.” But in terms of the practical, “What do I do tomorrow?,” critical thinking leaves me at a loss.

This is why, for just about the duration of this blog, I've been recommending that we “go big on argument.” When we place argument up against Willingham's definition of critical thinking, we find it to be at least a component of effective problem-solving, it's totally reasoning, and it's central to making sound judgments and decisions. Furthermore, when we have students conduct pop-up debates, we coach them to wrestle with Willingham's indicators of criticality, having to create arguments that are effective, novel, and self-directed.

So, even though argument isn't synonymous with critical thinking, I think we can do a good job of giving our students critical thinking practice when we teach them to argue and give them repeated opportunities to practice it. At the core of critical thinking, I believe, is argument. This distinction helps me breathe a little easier.

But there's a problem here, too — we next need to boil down argument. What, exactly, are we talking about here? Here's more on that.

Thank you to Daniel Willingham, whose articles to teachers are gifts that need spreading far and wide, and to Jerry Graff, who was the first person I can remember pointing out to me the difficulties in teaching “critical thinking” versus the difficulties in teaching argument. Jerry and his wife, Cathy Birkenstein, are the authors of the classic (and widely used) They Say, I Say: Teaching the Moves that Matter in Academic Writing.

Footnote:

- See Willingham's full article here. As with all of his articles, this one is well worth the time — I've gained more clarity from single Willingham articles than I have from entire books by other authors.

Leave a Reply