You ever get to a point in a project where you’re so doggone close to being done, but that final bit just feels super hard? That’s how this final installment in the “Student Motivation Like a Champ As We Head Back to School” series of guides has been for me. We’ve covered some super fun ground in this series, and I’m thankful to have contributed these longer pieces to colleagues near and far, but man — I’m ready for some lighter fare, you know?

Here's the table of contents we've covered in the series:

- Series Intro, Part I: On the Teaching of Souls

- Series Intro, Part II: The Path to the Head is the Heart

- Series Intro, Part III: Five Critical Qualities about the Five Key Beliefs, in Order of Actionability

- Credibility Guide: Three Simple, Robust Methods for Building the Credibility Belief

- Value Guide: Three Simple, Robust Methods for Building the Value Belief

- Effort Guide: Three Simple, Robust Methods for Establishing Effort in the First Weeks of School

- Efficacy Guide: Three Simple, Robust Methods for Establishing Efficacy in the First Weeks of School

- Belonging Guide: Three Simple, Robust Strategies for Building the Belonging Belief (here today!)

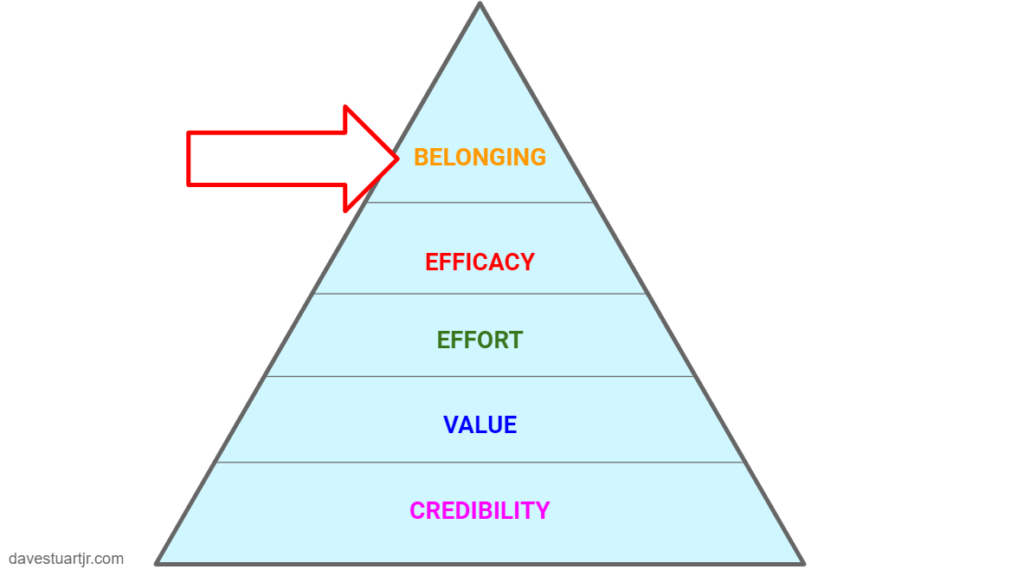

And here’s where we’re going today: top of the mountain!

Let's bring it all together with Belonging, shall we?

I. Things ya gotta know about Belonging in the classroom

Here's what Belonging sounds like in the heart of a student. 1

So this is what we're after when we're trying to cultivate the Belonging belief in the heart of a child.

- People like me do work like this.

- I belong here.

- I fit in this place.

- There's a match between my identity and this work that we're doing.

- It's not weird that a person like me is in a class like this.

- My experiences in this class aren't unique to me — most people experience these things.

Let's pull out a few key ideas from research and practice.

People like to fit.

You and me and our students have a thing in common: we prefer to act in ways that fit with how we think of ourselves. (I like how researcher Daphna Oyserman calls these identity-congruent behaviors in her Pathways to Success through Identity-Based Motivation.) So our goal as a teacher cultivating Belonging is to make it so that as many of our students as possible can find a path to linking the work we need them to do to their identity. We want them to think in their hearts, “Yep — it makes sense that I'm writing (or jogging or coding or reading or debating or studying) right now. That fits with who I am.”

The easiest path to Belonging is to become great at cultivating the rest of the five key beliefs.

There's a reason I've shifted Belonging to be at the top of the mountain. If you take care with cultivating the rest of the five key beliefs, you make Belonging a heckuva lot easier for students.

Look at how Credibility, Value, Effort, and Efficacy increase the odds that our students will sense that they fit in our space:

- Do they trust you? Do they think someone like you can help someone like them grow in mastery in your class? That’s Credibility. Folks want to work and be and learn and live in places where the authorities know what the heck they are doing. Just by trying to consistently demonstrate care, competence, and passion as a teacher (CCP, remember?), I'm making it easier for students to think, “Yeah, even someone with my academic background or my identity facets can fit in a place like this.”

- Do they want to belong? Are history or math or Phys Ed classes even the kinds of places that a student wants to be a part of? That’s Value. Each of our content areas has unique value propositions; as apologists, you and I seek to find and joyfully exploit these. How does mathematics link to flourishing? How does Phys Ed link to getting a good job? How does English language arts make you better at going on dates? That last one sounds a bit silly, I know, but as an ELA and history teacher I'm allllllways pondering new ways to communicate the goodness I've got on tap every day with rigorous learning in my classroom.

- Do they know how to belong? Okay, Mr. Stuart, we're going to write a lot in here. But I don't know how to write well. I can't run, Ms. Smith — how in the world am I going to do this mile challenge you're talking about? I've always done poorly in science, Mr. Vree — how can I learn to do the reason scientifically thing you're talking about? This is the Effort belief. Don't misunderstand — we're not after hand-holding our students or insulting what they are capable of; this is the opposite of having low expectations for them. It's just that you and I are going to be the kinds of people who teach the heck out of all of it — we're teachers. So we're going to show everyone what good, effective effort looks like; we're not doing “sink or swim.”

- Do they believe that they can belong? Is it really possible for someone like them to enjoy this book? To write this essay? To have a coherent conversation in French? That’s the Efficacy belief.

Belonging is the culmination. It touches a fundamental human need — we want to belong. We want to be with people who receive us, know us, value us, respect us. We want to matter like that. But it doesn't happen through good intentions alone! Not even close.

It’s ambiguous.

Here's where Belonging gets tricky: a lot of it comes down to how we interpret the signals we receive in a given environment.

By signals, I mean things like:

- Someone smiles at me.

- The teacher hands me a paper that has a B- on top of it.

- My friend ignores my wave.

- The teacher ignores me when I call out an answer.

Every day, our students receive dozens of signals like these, and all of them are interpreted through the lens of Belonging.

There's just one problem: these signals are ambiguous.

- Did the person smile at me because they're glad I'm here, or because they're trying to be nice to the misfit kid in the class?

- Did the teacher give me this grade because I deserved it, or because he felt sorry for me, or because it's just what I earned?

- Did my friend finally decide to not be my friend anymore, or was she just preoccupied?

- Did the teacher ignore me because she doesn't like me, or because she thinks I'm dumb, or because she was focused on something else?

Like a giant Plinko board, stimuli enter our students' awareness and end up in the “proof I don't belong” or the “proof I do belong” bins. The trick for us as teachers, then, is to help bias our students toward attributing the things they'll experience in our classroom as proof that they DO belong. We want to influence attribution.

- When a student succeeds:

- We don't want them to think, “Oh, just a fluke — folks like me don't succeed in places like this.”

- Instead, we want, “Yep — I worked for this, and I came out positively. Folks like me can succeed in places like this.”

- When a student fails:

- We don't want them to think, “Of course I did! And you know what, I'm probably the only one. Everyone else in here is successful, but people like me aren't.”

- Instead, we want, “Okay, I failed. I'm not happy about it. BUT failure is a normal (and hard!) part of the learning process, and it happens to all kinds of folks.”

- When a student gets extra attention:

- We don't want, “It’s because I’m weird here. People are giving me special attention because they don't think I belong. I'm a charity case to them. They don't think I'm smart enough.”

- Instead: “This is cool! It's nice to get extra attention sometimes, and folks like me sometimes get it because we matter and fit in places like this.”

- When a student is getting less attention than normal:

- We don't want, “It’s because they don’t want me here. I'm a nuisance to them. They've given up on me.”

- Instead: “Not everyone gets extra attention all the time. That's okay. It’s normal to not always be the center of attention, and I know folks will attend to me if I ask, no problem.”

See what we're after? Circumstances can be interpreted all kinds of ways, and this is why the Belonging belief is so important. It’s like bending one’s interpretative lens toward habitually interpreting things in a manner that supports ongoing motivation. It’s like a special protection spell cast over our identity — “No matter what happens in here, I’m not a reject. I belong. I fit.” And it's possible for each of our students.

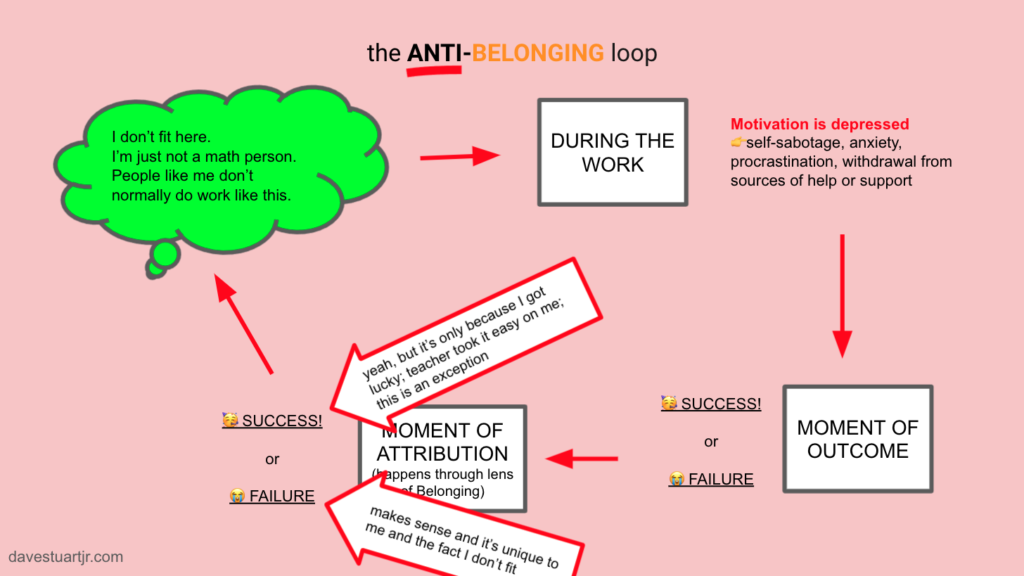

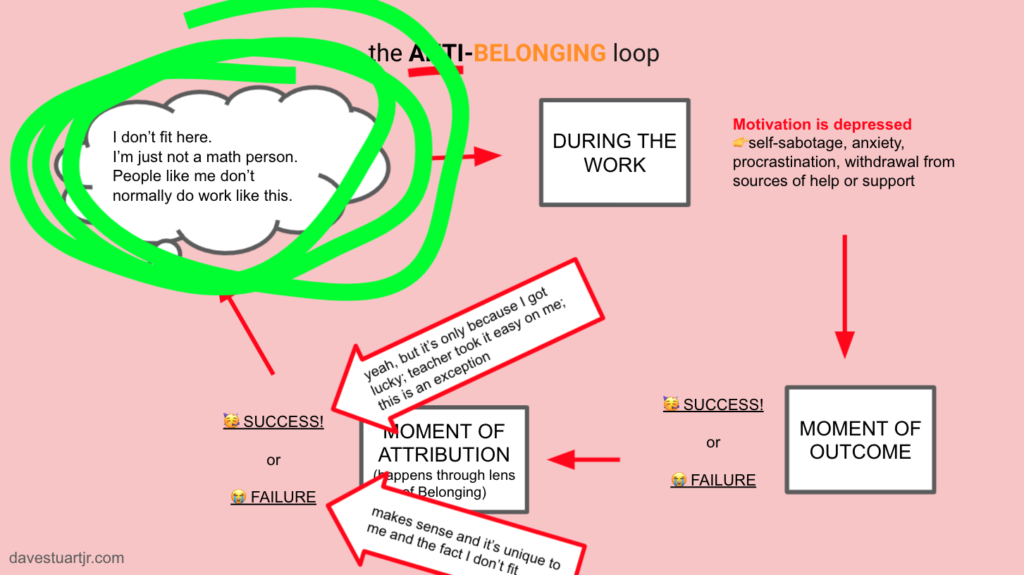

It’s recursive.

This last one's probably easier to explain with a diagram, so let me try that.

One hour later…

Okay no, that's not clear either.

Let's try a video:

Ahhh… much better. For my colleagues who prefer my content written, my apologies! I didn't have time to write.

The idea is that the ways that we attribute stimuli as either proof OF or AGAINST our Belonging can then reinforce themselves into either a virtuous loop or a non-virtuous “doom” loop. So what we want to do is intervene in the places that we can, as efficiently as we can.

Which brings us to our three practical methods for influencing Belonging.

II. Three Practical Methods for Cultivating the Belonging Belief in the Classroom

Three things to try.

Strategy #1: Track MGCs + 2×10 for extreme cases.

I know, I know. I already said this — see Strategy #1 here, or this video, or this old blog post, or Chapter 2 of These 6 Things.

But for real. Tracking Moments of Genuine Connection works because it begins to disrupt that first stage in the anti-belonging doom loop.

Wait, maybe this teacher sees me for… me. Maybe I'm more than a walking stereotype to them. Maybe I'm an individual.

Have a super tough student? Bring it back to the eighties with 2×10 — just for that one student.

But, Dave, I've got half a class of tough students!

Still, select the one you're having the hardest time with.

It’ll help not just them, but the whole class.

Strategy #2: Don't leave learning strategy to chance.

In one Camille Farrington et al's Teaching Adolescents to Become Learners, after a rigorous critical research review, the writers suggest that there are two points of max leverage for teachers who wish to help all students become learners:

- academic mindsets (I call these beliefs), and

- learning strategies.

When we go out of our way to provide students with hyper-clear, hyper-efficient instruction and modeling and checks-for-understanding and feedback around not just the content and skills we're seeking to help them learn but also the strategies that work best for acquiring that learning, watch out!!! We create the conditions for true equity and inclusion because we've removed the curtain that stands between so many of our students and success in their work.

It's the old John Wooden story about teaching college athletes to put on their socks and shoes properly. He didn't do that for some players; he did that for all of them. He didn't take forever teaching it to them — but he did still teach it. Nothing was too small for his teaching to attend to. All of his players had room to get better in even the smallest of areas.

This is Belonging fertilizer, my friend.

So anything you want students to do, teach them to do it strategically and well.

Quick example:

- Having students take notes? Look at different note-taking styles. Repeatedly remind students what notes are for. Give them different constraints in their notes — tonight, set a timer for 30 minutes, and when it's done, you're done; today, you get only half a page to create the best representation you can of what we'll be learning about. (I'm working on an article about how I teach note-taking. Make sure you're subscribed to the newsletter and the YouTube so you don't miss it.)

Strategy #3: Get ‘em in the pool.

Ms. Rita is one of my favorite teachers ever. In four one-hour lessons, she taught each of our four children how to swim. The transformation was real: my kids went from “I hate putting my head underwater” to “I like swimming and am getting better all the time.” It was a shift not just in competence but in identity.

This is a clip from the last day of Laura's swim class with Ms. Rita. In this video, our little blondie is three:

So here's the key question: how in the world does Ms. Rita so consistently produce a dramatic shift in identity for her learners? They go from “I hate swimming and don't want my head underwater,” to “I like to swim and am happy doing it.”

I speak about Ms. Rita's magic often in my workshops and keynotes, and here's an excerpt from a talk I gave in New Orleans several years ago for the International Literacy Association's annual conference (Ms. Rita discussion starts around the 2:30 mark).

Just want the gist? It's the fundamentals we've been talking about this whole series:

- Be credible. Care about students. Know how to teach them. Be passionate about what and why you're teaching.

- Create the conditions for success. Clear instruction. High challenge. High support. Normalize difficulty.

- Be right there with them. Beside them, amongst them, in front of them, behind them. You're the teacher, the coach, the guide, the guru. Don't feel that confident yet? Keep your head down, keep asking questions, keep doing the work, keep your focus. It's our job to know how learning works and how to increase it's effectiveness. That's a good — and a hard — job.

Do you want students to improve their mile time in Phys Ed? Show them how to walk: arms, legs, back, breathing. And then walk with them, warmly yet firmly accepting nothing less than walking.

Do you want students to write every day in your class? Show them how to complete a written warm-up: where to write it, how to come up with ideas, how to overcome the inner editor, etc. And then walk around coaching them, warmly yet firmly accepting nothing less than an attempt.

Do you want students to listen to each other during discussions? Show them what to do with their bodies, their hands, their minds. Make listening explicit. And then require it by asking them to paraphrase before they speak in the next discussion. (And give them tools for knowing how to do that.)

These have helped me a lot.

This series of articles has been a labor of love, and I hope it helps a lot of teachers create “more learning, less stress” — in their classrooms, in themselves.

Much love. Please share these articles generously. Encourage folks to subscribe to the blog and the videos.

Your sharing makes my creating possible!

Much love, colleague,

DSJR

The Footnotes

- As we discussed in this article, beliefs are knowledge held in the will — meaning they are not necessarily things that we think about or articulate.

Leave a Reply