When Connie (not her real name) ran out of my classroom last spring, tears streaming down her face, I felt like a horrible idiot. On the first day of school, she had voluntarily identified herself as being anxious about public speaking on her index card, but through a simple progression from Think-Pair-Share experiences to Pop-Up Discussions and Debates, I had seen her successfully overcome her anxiety enough to speak to the whole class. Connie participated in not just our first Pop-Up, but in every one that followed. I can still picture her all of those times, standing in front of her peers, combating her dragon with courage and poise.

But then this day in the spring happened, and Connie ran out crying.

Two kinds of anxiety, and one of them is good

When I first read Connie's index card, I felt for her. In my own life, anxiety (around public speaking in particular) has been far more experiential than theoretical. I was the kid who got sick to his stomach when he knew he was going to have to speak in class. I sincerely questioned the sanity of anyone who would willfully give a speech or enter the drama program. (This hasn't completely gone away, either — good luck finding me eating breakfast prior to a speaking engagement!)

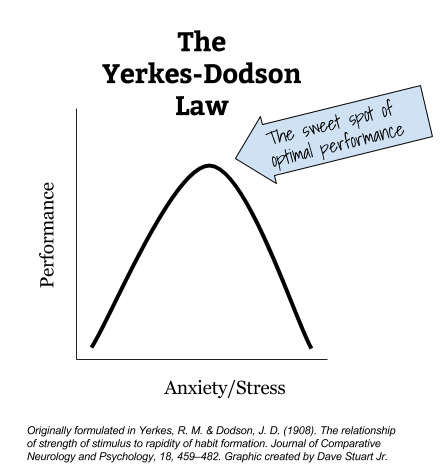

But here's the interesting thing: while too much anxiety makes life miserable, too little can actually leave us falling well short of our potential. Researchers have categorized two kinds of anxiety, labeling the helpful level facilitating anxiety and the unhelpful, painful level debilitating anxiety [1, 2]. In essence, researchers find that anxiety works akin to something called the Yerkes-Dodson Law (see Figure 1), which posits that there is an optimal amount of arousal or stress (or, in our case, anxiety) — too little or too much, and you don't maximize your performance.

And this makes sense, right? For example, anyone who has participated in a National Writing Project professional development experience knows the performance-enhancing power of a little bit of anxiety. At an NWP workshop or summer institute, teachers work with a small writers group of peers, and they routinely share their writing aloud — reading, for other adult ears to hear, words that they dare put down on the page. This produces a level of anxiety in most participants — anxiety they wouldn't experience when just writing for themselves or for their students. The intensity increases when, at the end of an NWP experience, writers share a piece with the entire, larger group — usually around 20 or 30 people, all of whom are educators.

Yet the National Writing Project is consistently cited as one of the best professional development movements in the United States — even though it consistently makes participants feel somewhat anxious.

The point: not all anxiety is bad. A moderate level of anxiety facilitates performance and growth, but too much is debilitating. And that debilitating kind of anxiety is what Connie seemed to teeter on the edge of, all of last year, day in and day out.

The growing problem of debilitating anxiety in American students

Connie wasn't the only student who had serious problems with Pop-Up Debate last school year. Throughout the year, I would periodically receive an email from one of our counselors, explaining that intense anxiety for this or that student needed to preclude his or her participation in further whole class discussions or debates. All told, by the end of the school year I probably had 6% of my students having been excused from at least one Pop-Up through official channels (e.g., the guidance counselor). When compared to my typical rate of 0% (and when we make the reasonable assumption that there were more students struggling with this than those who went and spoke to the counselor) that is a big, troubling increase.

As I looked into this further, I found some evidence that debilitating anxiety nationwide is on the rise and has been for some time. We see the tail end of this trend in surveys showing a 10% increase in the amount of college students seeking counseling services for anxiety over the past ten years [3], but some researchers have looked much further back. Jean Twenge, for example, found that over the past 50 years adolescent and young adult anxiety has risen dramatically [4]. There are plenty of fascinating theories for why this is, some of which I've read and some of which I hold. Could it be a shift toward externalism, or (as is Twenge's theory) toward materialism [5]? A shift away from play [6]? A decades-long, increasingly destructive fixation on national- and state-level policy measures that exalt dystopic accountability structures over saner, less measurable efforts to educate the whole child?

I don't have all those answers, but while I think the causes could give us insight into some potential solutions, the good news is that there are things we can do to help our students combat debilitating anxiety while still building classrooms that optimally develop the potential of our students.

Swords for the dragon

The following will be a short list of recommendations for helping our students combat debilitating anxiety. Those that aren't my ideas will include citations; if you don't see a citation, you'll know it's just me (and therefore based more on hunches than expertise). None of these are silver bullets, but they certainly are swords.

1. When goal-setting, encourage kids to set goals that are entirely within their control. “I will earn an A on my essay” is less controllable than “I will have three friends and one adult read and offer feedback on my essay,” which in turn is less controllable than “I will reread and revise my essay three times, three separate nights this week.” The goal here is to help our students hone their ability to focus on things they can control. One reason grade-obsession is so harmful to kids is because grades hinge on many factors outside of their control.

2. Praise students for their achievement of intrinsic goals. John Wooden is a great example here — he was the winningest college basketball coach of all time, yet his definition of success was “peace of mind that is the direct result of self-satisfaction in knowing you did your best to become the best that you are capable of becoming.” He achieved incredible extrinsic success (wins, championships), but his definition of success, for himself and his teams, was always entirely intrinsic. Twenge's research [5] suggests that teens are increasingly focused on extrinsic goals — popularity, material possessions — and she hypothesizes that this greatly contributes to their anxiety.

3. Reflect on past wins. This is from Heidi Grant Halvorson's 9 Things Successful People Do Differently:

“Perhaps the single most effective way to increase your confidence is to reflect on past successes. When you find yourself full of self-doubt, take a moment to recall (as vividly as possible) some of the goals you have achieved, and the obstacles you overcame to do it. You can even make this an if-then plan: If I am doubting myself, then I will remember the time that I ________________. Studies have shown this to be an effective strategy for increasing confidence with both anxious test takers and jittery pregame athletes.”

Back to Connie

After class that day, I sought out Connie and spoke to her. It turned out that she had been made particularly anxious by the video camera I was using to film the pop-up debates (I was conducting a study with Character Lab that called for the use of film) — the camera had been all it took to finally push her beyond the place she could perform, and so she broke down and ran out of the room in tears. It was one of those moments — so common in my career — where I could only think, “Duh, Dave. Nice going.” I told Connie I understood and was sorry, and we parted ways for the day.

That afternoon, I reflected on how sincerely proud I was of all that Connie had done that year — she had spoken in nearly a dozen Pop-Up Debates, and she had worked productively in Think-Pair-Share situations and Conversation Challenges. Perhaps most graciously of all, she had trusted me enough to try these things, to walk out on that tightrope each day, daring to do a very hard thing.

While the thoughts were fresh, I wrote her a card; the following day, I surreptitiously handed it to her. In it, I explained my pride in her, and I gave a rare permission: she was exempt from verbally participating in the school year's remaining handful of Pop-Ups. After class, Connie walked up to me and did something I would not have expected: she asked me if she could have a hug.

More than six months later, I still wonder sometimes if I made the right call in exempting Connie from whole-class speaking situations. Recently, I read a blog post by Seth Godin, called “Widespread confusion about what it takes to be strong.” In it, he says that sometimes we confuse strength with “an unwillingness to compromise small things to accomplish big ones,” and he concludes that “strength begins with unwavering resilience” rather than “willful disconnect from the things that matter.” I think that's probably an important thought. As teachers, we have to keep our eyes set like flint on the long-term good of our students, which means that, especially in an age of rising debilitating anxiety, we need to create classrooms where students discover that it's good to be pushed beyond our comfort zones, that some pressure actually facilitates growth and performance in ways that no pressure never could.

But at the same time, we can't lose sight of the fact that not all situations can be run through the simple rules of pop-up debate.

Footnotes:

- I first learned of the difference between facilitating and debilitating anxiety in the abstract to Scovel, T. (1978), The effect of affect on foreign language learning: A review of the anxiety research. Language Learning, 28: 129–142. doi:10.1111/j.1467-1770.1978.tb00309.x. Find the abstract here.

- I found this review of the anxiety literature especially helpful: Essays, UK. (November 2013). Definition And Types Of Anxiety Literature Review English Language Essay. Retrieved from https://www.ukessays.com/essays/english-language/definition-and-types-of-anxiety-literature-review-english-language-essay.php?cref=1. The site seems a bit dodgy (I think you can buy essays there), but the cited sources in the essay seem to vet out based on the several I checked.

- Novotney, Amy. “Students Under Pressure.” APA.org. N.p., 2016. Web. 11 Aug. 2016. (Access it here.)

- Twenge, J., et al., (2010). Birth cohort increases in psychopathology among young Americans, 1938-2007: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of the MMPI. Clinical Psychology Review 30, 145-154.

- This is Twenge's belief. See “Generational Changes in Materialism and Work Centrality,” here.

- Dr. Peter Gray's insightful analysis on anxiety and play can be found here.

Erin MC says

I work in a special education program in which 90% of my students have clinical anxiety. In classes of 6-8 students, speaking in front of the class can cause debilitating anxiety. But speaking in front of others is still a necessary skill, so we must try to persevere. The most helpful thing you can do for these students is give them time. Let them know there is going to be a debate/presentation/discussion/etc. Give them time to prepare for it mentally, as well as giving them the questions/topics and time to jot down some notes. It may not be a “pop up” but it is speaking in front of others. Baby steps.

Keri Austin-Jaousek says

I have a new job this year, supporting at-risk students with their academics . . . and whatever else surfaces. The number of students who battle some degree of anxiety is bewildering. Dave, you always give voice to the exact issues we are all trying to resolve in our classrooms, and I appreciate being able to hear a sane, well-balanced treatment of each issue. Thank you!