Before I start lathering at the mouth about PVLEGS, let me just state plainly that this acronym for effective speaking was developed by Erik Palmer, a professional speaker/edu-consultant/former-teacher and the author of Well Spoken, Digitally Speaking, and Teaching the Core Skills of Listening and Speaking. To my knowledge, Erik is doing the. best. work. around teaching kids to perform all manner of speaking tasks.

I'd also like to take a minute to thank my friend and first editor, Tom Schiele, who first told me about Erik Palmer. Tom may have thought little of the introduction, but PVLEGS has been one of my most personally exciting discoveries of the 2013-2014 school year, mostly because of how it has helped improve the speaking of my high school students, my college students, and myself.

Speaking and listening are a big freaking deal, and they are often neglected in K-12 schooling

As Erik Palmer quickly points out in Well Spoken: Teaching Speaking to All Students, oral communication skills are top on the list of what employers want (in recent NACE Job Outlook surveys, “the ability to verbally communicate with persons inside and outside the organization” has consistently ranked in the top 4 skills employers most desire in job candidates). This is one reason I appreciate the Common Core: though there are still plenty of problems with the implementation process around the nation, they at the very least make clearer that speaking and listening are crucial skills.

Palmer begins his book with a simple question: examine a given week in your adult life, and tell me what percentage of your communication is written, and what percentage is spoken? He argues that, while writing is obviously a crucial life skill, writing does not suffer the utter lack of clear, helpful instruction in K-12 schooling that speaking does.

I find it hard to argue with that. My own experience speaks to it, as both a student and an ELA and social studies teacher.

And so, armed with two beliefs — first, that I must constantly give my students opportunities to speak about interesting, complex things (this is why I have them read lots of complex texts, some of which they choose and most of which I choose); and second, I must constantly teach them how to organize and express their ideas (They Say/I Say is our go-to resource here) — I present to you how Palmer's PVLEGS has helped me teach my students the characteristics of effectively performed speaking.

Speaking is a performance-based communicative task

From Erik Palmer's Well Spoken:

How a speech is performed may be more important than how it is built. If the speaker cannot deliver the speech well, no one will ever notice how well it was written. As Chris Witt points out, ‘Knowledge isn't power; communicating knowledge is” (2009, 5). The most brilliant ideas are worthless if the speaker can't deliver them.

How many of you cringed when you read that? And yet how many of you have to admit that what Palmer is saying is true? This is one reason I respect Palmer; he doesn't hold punches.

It is simply true that if our kids are lifelong readers who can't communicate effectively, if they love history or science but can't talk about it in a compelling manner, if they have grit but don't know that speaking is something to apply grit to, then rather than flourish, they are likely to flounder.

(Feel free to add your voice to this argument, by the way — add your comment down below.)

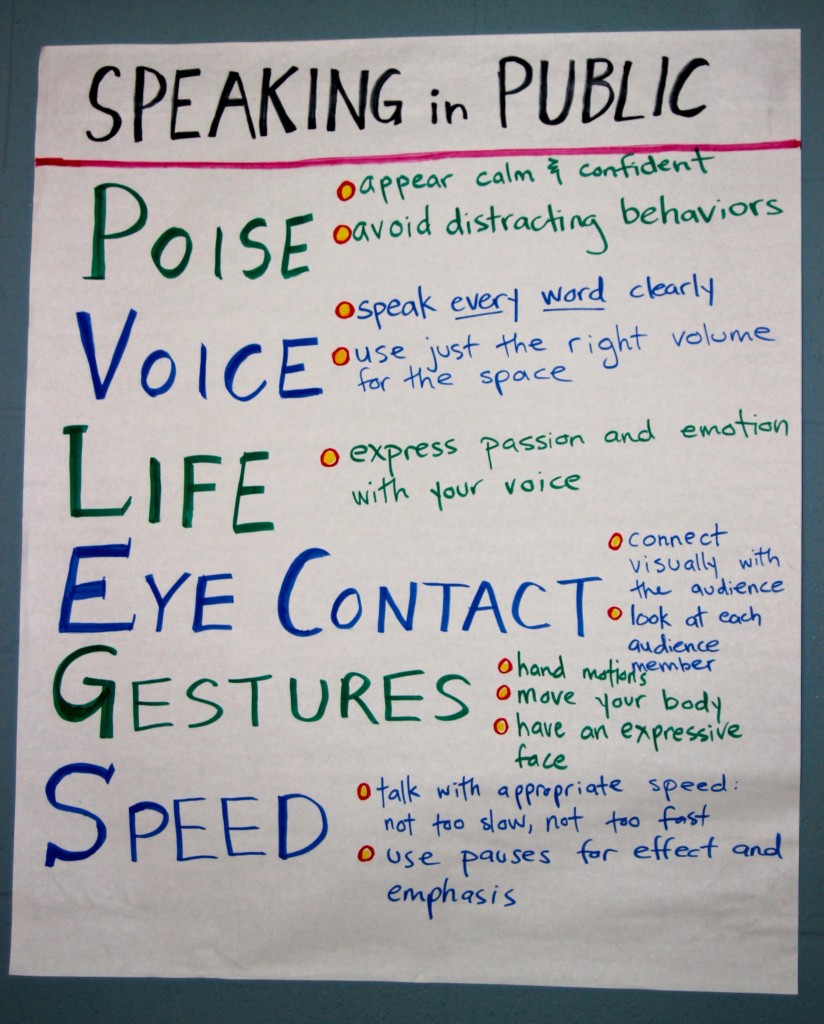

Now let me share what I've been so excited about: PVLEGS. Palmer has a whole website about PVLEGS, but here's the gist: PVLEGS is Palmer's way of simplifying how we teach and assess student speaking performance. PVLEGS does not include content (in Well Spoken, Palmer devotes an entire part of the book to building a speech), and I won't get into Erik's rubrics (they are beautifully simple, however — check them out on his site).

So what is it, exactly, that makes an effectively performed speech?

Poise: Calm confidence

From Erik Palmer's Well Spoken:

The truth is that all speakers have a degree of nervousness. Even a professional speaker with massive experience will have a heightened level of excitement before a presentation. It is also true that if that nervousness is obvious, listeners can be distracted and miss the point of the speech. This is why the first skill needed in performing a speech is poise. Webster defines poise as an “easy, self-possessed assurance of manner… pleasantly tranquil” (Merriam-Webster 1998, 899). The key to performing a speech is to appear calm and assured even when we may not feel precisely that way (or even remotely close to it).

The key breakthrough for my students here, initially, was that poise is a skill — it's a thing you can learn, practice, and improve. In the beginning of the year after some of our early debates, I always love asking my students to raise their hands if they were nervous. It is awesome for them to see that most of their peers are just as jittery as they are; misery loves company, I suppose

Students love explicit instruction, so I borrow from Palmer's chapter on poise and teach my kids that, specifically, this skill is about:

- Appearing calm and confident

- Realizing what our annoying tics are and training ourselves to stop them (one of my tics is fidgeting with a coffee cup)

- Being intentional about stance, movement, and posture

How can students gain poise? Palmer has a whole section of tips in Well Spoken — one that I began using after reading the book is right before taking the stage, counting slowly to five several times, taking deep breaths with each number. (So much of poise is about gaining control right at the start; usually the longer we speak, the more comfortable we get.)

Perhaps the most basic (and important) way to help students gain poise is giving them many chances to speak during your course. And just to be clear, by chances I mean requiring them to talk. I have kids with intense fear of public speaking at the start of each year, and all of them are confident by the end. This isn't magical Mr. Stuart; it's giving them the gift of experience.

Voice: Every word heard

From Erik Palmer's Well Spoken:

A good speech is a good conversation magnified. The speaker retains his basic conversational style but uses animation and volume suitable for a larger audience… You don't want students to imitate any style or person. You should, however, point out to students that there are different types of voices and you should begin the process of having them think about their voices. Some people have very strident voices, for example, making it tiring to listen to them. Help students become aware of how they sound to avoid such problems.

There are three elements of voice students work on: volume, enunciation, and avoiding odd vocal patterns like ending each sentence with a questioning tone or fading away at the end of each sentence (this latter vocal pattern is common in my students before we talk about it).

Life: Insert passion

From Erik Palmer's Well Spoken:

Listening to students' speeches over the years, I was often reminded of a time when I took my four-year-old son, Ross, to a school event for his older brother. The principal was droning on and on about something, and, before I could stop him, Ross had put both hands to his mouth, made a loud raspberry sound, and said, “Bor-ring!” As a parent, you are sometimes put into a position of having to tell your child he is wrong, even when he is right.

Awesome anecdote

Life is about adding emotion to our voices — showing that we actually care about what we're talking about. Very practically, then, life is about inflecting our voices in a manner that expresses an intended feeling, like excitement, joy, sadness, fear, disappointment, humor, amazement, or anger.

One mini-lesson Palmer shares involves giving students a simple phrase, like “I don't think you're wrong,” and then having them play around with the phrase to make it feel sad or happy or angry or condescending.

Eye contact: Engaging each listener

From Erik Palmer's Well Spoken:

Students… need to direct their vision toward the individuals in the audience. They aren't speaking to a group; they are speaking to many different people. It may seem intimidating to look at each person in the audience, but it is necessary.

There are two key points in eye contact: first, students need to work on meeting the gaze of as many people in the audience as they can; second, students should familiarize themselves with their speech rather than memorize it.

Gestures: Matching motions to words

From Erik Palmer's Well Spoken:

Watch people in some public places as they converse. Look around a restaurant or coffee shop. Sit on a bench in the mall and watch people walking by. Sneak a peek at friends a few seats over on the bus. Odds are that as they speak, they are gesturing. Hands move, faces move, and body positions change. This is typical and natural. Sure, some people use gestures more than others, but it seems that when humans talk, the body moves.

There are three kinds of gestures to help students become aware of: those with the hands, those with the face, and those with the body (e.g., shoulders, posture). Again, Palmer shares lots of mini-lesson ideas for this skill in his book.

Speed: Pacing, baby, pacing

From Erik Palmer's Well Spoken:

Excitement, nerves, and the adrenaline rush of showtime lead to increased speed. Your students are not lying when they say, ‘I know it was five minutes long when I practiced last night!' after you tell them that the speech lasted three minutes and forty-seven seconds. Giving a speech in front of Mom in the living room is not the same as presenting it to thirty peers in the classroom. …[T]o begin with, we should try to discuss with students the need to pay attention to the speed of the delivery. Then, we can teach them the more complex issues of pacing and using pauses.

There are three basic skills here:

- Be conscious of your speed while giving a speech

- Use the speed of the speech to enhance the message (i.e., pacing)

- Pause for effect

Picking on someone my own size: me!

Prior to picking up Palmer's Well Spoken, I had two pretty formal speaking situations: I gave the commencement address to our high school's graduating class of 2013 (click here to watch that — it was filmed in a gymnasium on an iPad, so the audio isn't the best) and I gave a keynote address at a regional conference for student teachers known as Fire Up (video embedded below; if that's not working, click here).

Now, let's have some fun and analyze my keynote with PVLEGS (this is exactly the kind of gritty, honest self-examination we want our students to do with their own writing, speaking, and living).

Poise

My most annoying tic in this speech is looking down at my speech on the podium. (We'll discuss this a bit more in Eye Contact). I do appear fairly calm and tranquil, but almost to a fault — my voice is often flat, which we'll discuss more in terms of Life.

Also, I undermine myself quite a bit in the beginning of the speech, saying that my audience was “first hour.” I've sometimes received the advice that admitting our nervousness is an all right way to both deal with the nerves and gain some rapport with the audience, but now that I've read Palmer's book, I don't think this is the most effective tactic.

Voice

My volume isn't much of a problem because of the effective sound system, but I don't enunciate super clearly (for example, see the word “died” right after 15:13 in the video). This is something I need to work on.

Life

This is a problem with my naturally laid back style — it can come off as pretty lifeless. This speech was fairly early in the morning, and that's even more reason why I needed to not sound like I had woken up only hours before! The larger the audience, the more I think Life really matters. I get a little Lifey starting at 16:46ish, but still, where was the life at the surprise twist (again, around 15:13)? Where is it at the beginning?

Eye contact

Though I do work the sections of the room when looking up from my speech, the problem is that I wasn't confident enough in my familiarity with the speech to look up for a majority of the time. I kept looking down, which, when I watch this over again, I find annoying and distracting — I'm sure some of my audience didn't mind, but others were likely driven nuts by it.

One of my fears as a public speaker who was a writer long before he starting speaking to people is that I'll say something I don't really mean, or I'll speak in a manner that's awkward or clunky or distracting. I've got to get over this through more practice and more bravery!

Gestures

This is mostly a strength for me — I use a lot of descriptive gestures (e.g., after 4:28 when I say “10, 20, 30 years”; at 15:55 when I say “flowed from her heart”), my face is often expressive, and my posture doesn't seem distracting.

However, I do at times make gestures that are confusing — like around 16:13 when I keep holding my hand in a loose fist and bouncing it with every word. I'm attempting to be emphatic, I guess, but it's not very emphatic when you emphasize every single word in a paragraph!

So if anything, I need to work on using gestures more intentionally and not doing them simply to do something. (Maybe cutting down on the coffee prior to speaking will help with this, too

Speed

My pacing is sometimes intentional — I think I do a decent job pausing for effect (and to insert facial expression), especially starting at 15:50. I wish I could go back and be a bit more strategic with pacing during the “I also hope for you no less than this” section (around 17:10) because I feel like I attempted to build up to a pacing crescendo, but it didn't come off as effectively as I would have liked.

Analyzing our own speaking is painful, and pain is good

Exercises like the one I just engaged in — looking back at a filmed speaking performance and analyzing it closely for strengths and weaknesses — hurt. Few things are as painful as watching how you speak; I've never found that I sounded as good as I felt I did while speaking. Know what I mean?

And yet, the only way we can become great at anything — at speaking, at teaching, at writing, at living — is by being ruthlessly honest about what we see in our performance. We as teachers tend to be bad at this; we tend to want to hear that we're great at everything. But we're not — the sooner we deeply accept that, the sooner we can become good at stuff. I say this because, in order for your students (and you) to benefit from PVLEGS, mistakes, failures, and growth must be normalized — you must model this.

What's at stake, ultimately, is our common goal here at DaveStuartJr.com — long-term flourishing. I'm excited about PVLEGS because it is one more tool I can use with students and myself to work smarter, not merely harder, at developing crucial life skills.

Kristie says

Wasn’t able to “watch your speech” due to tech difficulties, but listened to it and thought it was amazing and eloquent. Call me sappy…but I was teary and thinking this was exactly what our teachers at my school need to hear…You are wise beyond your years. This is coming from someone very near retirement.

Author says

Thank you! So excited to use this with my ELA students this year

davestuartjr says

You and they will love it!

Beth Groom says

I totally agree with you and Palmer that “how a speech is performed may be more important than how it is built.” I witnessed this first hand five years ago when my 8th graders had to perform a speech to the local Optimist Club with the topic “If I could change one thing in the world, it would be…” One of my students gave her speech and won. Her topic? She would prevent the practice of debeaking chickens. Seriously? Yes! It made me realize that you can put so much into the writing part that you forget to work on the communication part–some of the other speeches had better content, but no one delivered it with more passion!

vendija723 says

I stumbled into teaching a Readers Theater elective at my middle school this year, and I think we will study this as part of our work. Question–how do you pronounce it? PeeVeeLegs? P’vlegs? Like ‘privileges’ without an r?

davestuartjr says

Great question — PeeVeeLegs

Alex Murphy says

Hi Dave! Can’t tell you how helpful this framework has been. Big thanks to Erik Palmer for developing it and to you for bringing it to my attention. Do you have any suggestions for the best way to implement this schema into a lesson plan? (i.e. Is it better to introduce a few elements at a time vs. all at once? Any particularly helpful speeches to have kids analyze? Do you use this schema as a rubric for student speeches?)

davestuartjr says

Hi Alex! I like to introduce the whole thing in a single mini-lesson, and then in further mini-lessons elaborate on components of PVLEGS as needed. Best time for a speaking-related mini-lesson = right before a speaking activity (Conversation Challenge, Pop-Up Debate). I rarely use this for a rubric — instead, I explain to students why it’s worth working on, and I sometimes have them set PVLEGS goals prior to a speaking activity.

Alex Murphy says

Awesome. Thanks for the response! I am only just coming to terms with how critical speaking/listening are as language arts, and how little I have addressed them in the past. This is super helpful as I try to address that. Thank you for the time and energy you bring to this blog; your words have truly shaped me as an educator. Keep it up!

Ester Febryani says

Awesome…can’t wait to implement this with my junior students. Many great thanks..

henry says

this helped a lot really! I give really good speeches now and its all thanks to this amazing acronym PVLEGS