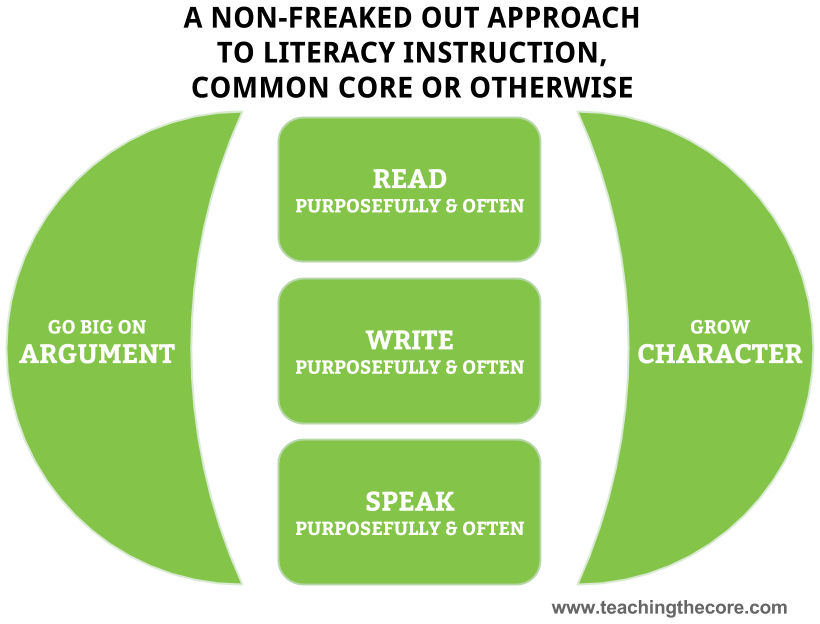

This past summer, I began playing around with a 2.0 version of the “non-freaked out approach” to Common Core literacy, hoping to hone the thinking I put forward a year and a half or so ago into something more useable, more balanced, and more timeless (you'll notice “close reading” died of buzzwordification).

Here's what I'm going to spend the 2014-2015 school year playing around with:

A couple things to point out, as I love being transparent with you all.

The trouble with having a “Common Core” blog

Not sure if you've noticed this, intrepid reader, but it's trendy in some states to have literacy standards aimed at college and career readiness but to call those standards something besides Common Core.

That's something I'm cool with — call 'em what you want, as long as they will promote the long-term flourishing of kids by aiming at simplified, widely applicable college and career readiness literacy skills.

Do your thing, Texas. Go get 'em, Indiana and Florida. Love you guys.

‘Merica.

So here's what's up, though — I just want to help where I can. And Texas is huge. So are the other non-Common Core states. So by saying “Common Core or otherwise,” it's like saying, “Hi Alaska — how you doin'?” I think what we talk about here in the Teaching the Core community is a bigger deal than a set of standards, and I would like to connect on these ideas with people from non-Common Core states.

With all that being said, I still find the Common Core very much worthwhile — my first “big kid” book comes out next month and is focused on the CCSS anchor standards — and the above framework comes from the past two years of trying to figure out how to actually implement these standards. But if you happen to have friends in non-Common Core states, you can now share Teaching the Core with them and they're less likely to chortle at you.

Here are some biggies I left out of the framework

Teaching the Core readers have sagely pointed out that critical elements are missing from the non-freaked out approach in the comments section of various posts (like this one) and in conversations on Twitter or in person.

I've thought these things through at length — especially the one below about self-selected reading and developing a love for reading in students, both of which are big topics in my district's language arts department — and I would like to explain below why several important things don't get a spot in the above framework.

In putting forward this approach, I'm embracing what Jerry Graff called “the doctrine of simplicity” in a recent conversation we shared in the Chicago area. The basic premise of this idea is that if more than one solution to a problem can achieve the same end, then the simplest of the solutions is the best one.

My theory is that the non-freaked out framework, by intentionally leaving out some of the things listed below, will have a greater likelihood of impacting the most students possible because, at its heart, it's simple enough to grasp in an hour and complex enough to explore for a career. I'm obviously not saying my approach is the only way to increase student literacy development across the content areas (I find Mike Schmoker's work in Focus to be superior to mine in just about every way, and fully attribute the seminal nature of his work to my thinking). I'm just saying this framework is one potential model to explore; by all means, we need to develop and experiment with more models.

So let me tell you about some things I left out.

Where's a love for reading? And self-selected reading?

This is a problem many (English teachers especially) have with the Common Core standards — there's nothing in them that points out the importance of getting kids to passionately enjoy reading, getting them to develop reading lives, that kind of thing.

I do believe every student needs to engage in self-selected (or “choice”) reading, to build independent reading lives, and to develop a love for reading. The two best books on this topic are, by my estimation and that of thousands of others, Donalyn Miller's Book Whisperer (ideal for elementary through middle school) and Penny Kittle's Book Love (ideal for secondary settings and especially high school). These are master English language arts (ELA) teachers who have written convincingly about making readers out of kids and adolescents.

I do believe every student needs to engage in self-selected (or “choice”) reading, to build independent reading lives, and to develop a love for reading. The two best books on this topic are, by my estimation and that of thousands of others, Donalyn Miller's Book Whisperer (ideal for elementary through middle school) and Penny Kittle's Book Love (ideal for secondary settings and especially high school). These are master English language arts (ELA) teachers who have written convincingly about making readers out of kids and adolescents.

In my 9th grade English classes, choice reading is a regular part of our routine, and I give my students time, space, encouragement, and one-on-one conferring to guide them toward developing a recreational reading habit. At the same time, I think ELA teachers are wise to avoid letting choice reading become the entire curriculum, as post-secondary settings require more than a love for choice reading (and professors I've spoken with seem to vigorously support that last statement).

With that being said, the non-freaked out (NFO) framework at the start of this post (and the bulk of my work) isn't for ELA teachers alone — nor are the Common Core literacy standards. As a result, the framework above doesn't include things that belong in the English classroom alone.

The framework is meant to help teachers across a student's school day with mastering the basic building blocks for literacy development, the basic things that, if we give students lots of chances to do and improve at them, they'll be more likely to flourish in the long-term than if we're constantly trying to come up with cute or epic activities.

Where's research? I thought that was going to be in this?

Earlier in the summer, I did have research in there (“Info saavy, not tech saavy”). The thing I came to realize, though, is that I have a ton to learn about teaching kids to conduct research effectively (it's one of my burning questions this year).

As Christopher Lehman's book helped me realize, research is a kind of reading and a kind of writing (and thus a kind of speaking). There are certain, effective ways for both conducting research and sharing findings. So I promise to work on that this year, but for now, you won't see it explicitly in the framework — it's a layer or two deeper.

But what about passion, man!? Where is passion in your !@$%ing framework!?

Easy on the language, friend. We don't speak that way here.

I do believe we as teachers should strive to instill passion in our students — for writing, for mathematical problem-solving, for scientific inquiry, for knowledge — but you won't find that explicitly stated in the framework above.

Trust me: I'm not a heartless dude who hates passion. I'm driven by passion — for Jesus of Nazareth, for my wife, for my daughters, for my students, for the thrill of writing a sentence that captures an epiphany, for the endless mountains of books there are to explore. I love great beer, great coffee, and great company.

I hope you're life swells with passion, too; life's not long enough to spend much of it bored.

But I — and we — have got to remember that we're paid to contribute to the long-term flourishing of kids, that they might proficiently pursue whatever their passions may be or become. Specifically, I'm paid to do this by teaching them 9th grade English and 9th grade world history, and I'm paid to hold as an end goal their increased college and career readiness.

I guess I'm just trying to say that I think us teachers sometimes get pretty idolatrous about our “right” to only teach and do what we're passionate about, because that, our thinking goes, is what's going to have the biggest impact on kids' lives.

But what if we can become passionate about just, you know, the challenge of teaching something we're not totally intrinsically thrilled by but that is a part of the curriculum regardless? What if we can become more alive at the thought of watching lights go on for our students rather than teaching that one text we've always wanted to teach or doing that one lab experiment we've always wanted to try?

I know there are plenty of horrific curricula out there and we've got to advocate against such things, and at the end of the day, make sure our students get a high-quality curriculum, but I'm just saying there's a time to put your head down and do the job, teach the curriculum.

Dave, that was the most insane tangent you've ever taken.

Yeah, that's probably true. I'm going to blame that one on travel fatigue.

I guess the point is the NFO framework is meant to be versatile across the content areas, and I just really need my ELA brethren to hear that. I'm not anti-choice-reading guy. I'm “let's make literacy make sense across a school day” guy.

Back to the framework.

This framework intentionally emphasizes argument and character development as uniquely powerful themes for producing college and career ready people

The reason “Go Big on Argument” and “Grow Character” are big croissant-shaped things is because I think they need to be embedded into a ton of what we do with reading, writing, and speaking.

Argument is basically rational, evidence-supported thought, and rational, evidenced-supported thought is kind of a big deal. (Though it's becoming less of a big deal — winking at you, Fox News and MSNBC. Love you guys. No, I don't.)

I'm still an apprentice of argumentation, but I like teaching my kids that there are three basic pieces to play with when we put forth our own ideas:

- Claim

- Evidence

- Reasoning that shows how the evidence supports the claim

The best way to support kids in doing this is to show them, explicitly, what each of these pieces looks like with brilliantly simple sentence templates like those that form the foundation of Graff and Birkenstein's They Say, I Say.

I also like to pound into my students' heads several hundred times per class period the fact that arguments in isolation basically are not arguments — which means we need to read/listen to, accurately summarize, and then put forth our ideas in relation to what others have already said or written. If we do this, kids will begin answering the “so what?” question that educators around the nation crave to see in their students' work. All of this, by the way, is derived from Graff and Birkenstein's They Say, I Say.

But isn't argument cold and heartless?

No. You are cold and heartless if you don't teach kids how to argue because:

The value of effective argument extends well beyond the classroom or workplace, however. As Richard Fulkerson (1996) puts it in Teaching the Argument in Writing, the proper context for thinking about argument is one “in which the goal is not victory but a good decision, one in which all arguers are at risk of needing to alter their views, one in which a participant takes seriously and fairly the views different from his or her own” (pp. 16–17). Such capacities are broadly important for the literate, educated person living in the diverse, information-rich environment of the twenty-first century. –from the Common Core's Appendix A, p. 25

(I take back the thing about you being cold and heartless. I didn't teach argument in an intelligible way until two years ago when I started reading the Common Core. Love ya.)

And isn't character not even in the Common Core?

It's totally not. But there's just too much research out there saying we've got to try everywhere we can in school to help students grow highly predictive noncognitive skills (I call them “character strengths” like KIPP schools because it's a bit less technical and implies that these things can be developed versus being fixed traits).

Also, fun side benefit of teaching character — you're simultaneously increasing your long-term impact on students and making your life easier as an educator.

Reading, writing, and speaking — do those in greater quantity and with increasing quality

For reading, we need to think hard about the number of age-appropriate texts we're having kids read, especially (if we're aiming at college and career readiness) the number of informational texts. Again, ELA teachers: don't throw things at me. I'm speaking to a broad group here.

We can't just assign texts — we need to teach our kids how to read them through simple strategies like Schmoker's authentic, redundant literacy template (found in Focus, which is the number one book I end up recommending in whole staff professional development situations because of how it treats K-12 environments and dedicates entire chapters to literacy instruction in math, science, and social studies).

Quantity matters.

Rather than spend days to pick apart texts through laborious close reading (a la the David Coleman approach picked apart masterfully in Smith, Wilhelm, and Appleman's UnCommon Core), I think we need to follow Schmoker's advice by setting quantifiable goals for how many texts students will read over the course of a year in each subject.

In English, how many short stories? novels? plays? articles? poems?

In science, how many textbook excerpts? articles? reports? procedure documents?

In social studies, how many primary source documents? articles? textbook excerpts? op-eds?

And the same questions ought to be applied to writing and speaking.

How many one-paragraph arguments will kids write per course? How about two-paragraph explanatory pieces? Etc.

How often will structured debate happen in each class? How often will students be required to participate in discussions that will be assessed with simple rubrics focusing on explicitly taught skills?

Quality does, too.

At the same time, it's not just about how much kids read, write, and speak — it's about the level of sophistication and complexity required in each of these situations, too.

We've got to make sure 9th graders get ample chances to read texts that on-level 9th graders are reading. Interventions should be made for below-level readers, but every kid deserves to be taught how to read texts on pace for college and career-level complexity, even if he or she is drastically below grade-level. I disagree with those who say kids simply won't read what they can't — I think can't is a highly flexible term that depends on much more than a kid's SRI level.

The same is true for writing and speaking. We need to provide kids with exemplar models of writing and speaking at a level appropriate to their age, and then we need to give them feedback that aims to be kind and honest, even when this means facing brutal gaps in their college and career readiness.

Reading to gain knowledge is huge as well.

Something I've not spent enough time exploring on Teaching the Core is the incredible importance of reading to gain knowledge. The Common Core mention the ability to build knowledge in the standards' introductory matter, but it's not emphasized nearly enough throughout the standards. Reading to know stuff is a big deal, both for college and careers.

I recently spoke to a group of professors at a local college and asked the professors what were some of the biggest skill deficits they see across the board. One professor in the nursing program said something to the tune that students are woefully unprepared to learn through reading, especially when that reading is assigned and especially when it's a textbook. There were a lot of heads nodding as this professor spoke.

I think that's a problem we in the content areas need to solve — we're talking about giving students access to careers in nursing, in computer science, in business; we're not talking about turning science class into reading class or math class into writing class.

There's a lot of work to be done here, obviously.

As I write these things, I'm fully aware that I've got a lot of work to do as a teacher — but that's what I like about the NFO framework laid out above. It's simple, right? Simple enough, I hope, to take in at a glance and to start working on after an hour or so.

Yet it's also complex once you start wrestling with its elements. How do we really teach kids to argue in the manner described in the Fulkerson quote above? How do we manage the vast range of literacy ability we're faced with every day in the classroom? How do we motivate students to do this hard work; much more importantly, how do we teach them to manage their own motivation? After all, we cannot build their literacy skills for them.

Big questions, my friends. No easy answers. But boy, what a pile of rewards for our students if we get a bit better at these things.

So here we go, Teaching the Core family. This little blog is entering it's third school year. I couldn't pick better people to embark on the journey with. Giddyup

Mary Lou says

Excellent points!

davestuartjr says

Thank you ML

Jennifer Engle says

“I’m addicted to your blog,” said the Texas educator. Thanks for putting all this out there and keep the thoughts flowing!

davestuartjr says

Yes! Jennifer! Yes! Texas!

terrimb says

Because I am in a private school, I love using the Catholic Social Teachings and Catholic traditional values as the “grow character” portion. It’s an incredible way to analyze their reading against the church’s teaching and expectations. I can now communicate what I’m doing using this graphic, thus increasing our administrators’, parents’ and peers’ understanding! Thank you for sharing this!

terrimb says

Oh, and I am in Texas, too!

Mike White says

Owner of the first 2017 reply!! I’m reviewing key posts as we embark on the Spring semester next week. From the artfully argumentatively intense Creative Writing class, my sophomores embark on the much-dreaded path-to-the-EOCII. THIRTEEN argumentative essays in, we completed the Creative Writing course fully-engaged in They Say/I Say moves, and I’m focusing on the simple 9-Step Into-Thru-Beyond instructional framework. We have an online textbook and myriad opportunities to grow and flourish!!

davestuartjr says

I love it, Mike. May this be a great year for you, your professional journey, and your students!