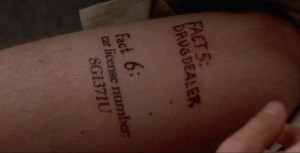

The film Memento (2000, directed by Christopher Nolan) is the story of Leonard, a man with one abiding purpose in life — finding and bringing justice to his wife's killers — and one serious handicap: he is unable to retain short-term memories. As a result, Leonard develops a system of reminders — including tattoos like those in Figure 1 — and he uses this system to overcome his condition. (Or does he? Muah ha ha.)

When I look at my students and I look at myself, I see that we have something in common: we are all pretty much the opposite of Leonard. We lose sight of our single, abiding purposes and instead keep in mind only the latest short-term memories — our Twitter or Facebook streams; the book we're reading right now; the most recent show we've binge-watched or podcast we've heard. Leonard could remember only his one abiding purpose while most of us are hard-pressed even to define ours.

Yet we have something in common with Leonard. His problem was externally initiated (he got hit in the head), internally located (his condition), and practically solved (his reminder system). Our problem is externally initiated (more choices, or noise, than ever before in human history), internally located (we form habits around our favorite sources of noise), and practically solved.

It's that latter bit — the practical solutions to our problems — that I'd like to write about today. And before I start, let me remind the reader that the solutions to complex problems need not be complex; in fact, Stanford and Harvard profs Kathleen Eisenhardt and Donald Sull (respectively) would caution against complex solutions.

From their fascinating book Simple Rules: How to Thrive in a Complex World (audiobook):

Meeting complexity with complexity can create more confusion than it resolves… Applying complicated solutions to complex problems is an understandable approach, but flawed.

Here's the question, then: how do we tattoo upon our lives the right kinds of noise — the kinds of simple reminders, like Leonard's facts in Figure 1, or Pope Francis' piece of paper, or a simple sentence on a bulletin board — so that we can avoid leading noise-dictated, constantly derailed lives?

Pope Francis' piece of paper

While the legacy of Pope Francis has yet to be seen, commentators across the spectrum seem to agree that his ability to remain true to his beliefs despite the unimaginable “noise” of papal life is remarkable. We think our jobs as educators are demanding, yet he's responsible for leading the world's 1.2 billion Catholics and leading an institution whose age is measured not in centuries but in millennia. He's made headlines for everything from riding the bus instead of the papal limousine [1], to washing and kissing the feet of juvenile delinquents [2], to declaring that church doors should remain unlocked in the wake of the Paris attacks [3], and all of these things seem to flow not from external pressures, but from within a settled mind and heart.

How does he do it?

One of the secrets to Pope Francis' poise amidst noise, it turns out, is a simple piece of paper.

From Pope Francis: Why He Leads the Way He Leads, by Chris Lowney:

Shortly before his ordination as priest, the thirty-two-year-old Bergoglio wrote out a short credo (the word means “I believe”) in a moment of what he called “great spiritual intensity.” He has kept the paper ever since, showing it to an interviewer nearly four decades later. It's neither a theologically precise creed like the ones Christians recite in church, nor is it a sterile philosophical treatise that one might defend as a dissertation. Instead, he wrote it as if planting a stake in the ground that would always remind him of his core convictions. It is deeply personal, and, therefore, wonderfully idiosyncratic; it reflects his Christian beliefs, but always through the prism of his own concrete history. Not, for example, “I believe in an afterlife,” but, as he wrote it, “I believe that Papa [his father] is in heaven with the Lord.”

What a powerful exercise: record in about 200 words, less than a page, your deepest beliefs and aspirations about yourself, your key relationships, humanity, God, and your role in the world.

Practical implications

First, in line with the above quoted Simple Rules, the solutions to our noise-induced aimlessness need not be complex. Francis, in an inspired moment, wrote a less-than-200-word personal credo. Later in the passage, we learn that he cultivated the habit of regularly reflecting on that credo and whether he was living it out (or whether it needed editing).

- Do you have a similar, succinct expression of your beliefs about the world and your place in it?

- How can you cut wasted moments from your life so as to make time for creating and reflecting on such a credo?

Second, if the pope can keep in mind who he is and what his purpose is despite the pressures of his job, then we can, too. If you think the pope has an easier time remaining true to his purpose than today's American public school teacher, you're not thinking clearly. But Dave, you say, he's got the power! Ain't no policymakers or angry parents or micromanaging administrators holding him back! Well, that's true — except that the pope's every action and word is examined by the world's media or critiqued by his smartest colleagues. Yes, being a teacher is hard; no, it can't be harder than being the pope.

- Do you make excuses for living a noise-dictated, derailed life?

- Do you explain away why you currently feel powerless or purposeless in your career as an educator?

My bulletin board

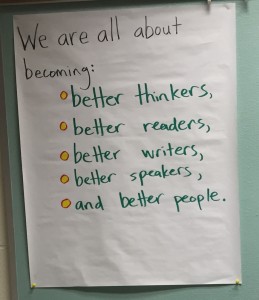

So let's head from one end of the spectrum — the decades-tested credo of a former TIME person of the year — to the other — a comparatively unproven, handwritten piece of chart paper on the bulletin board of a random teacher-blogger in Cedar Springs, Michigan (see Figure 2).

I've written before about how we each need to define our Mount Everests (here's a brief activity for leading your staff or yourself through the task) if we're to maintain our sanity, effectiveness, and autonomy as educators. The question, then, is how do you set yourself up to be persistently reminded of your Everest?

I've heard of some folks who take their Everest statement and put it on an index card and tape it to their computer monitors. But perhaps there's a benefit in sharing it with others — in the staff lounge, or (as in my example) in the front of our classrooms. This way, it's not just the reminder that can remind us of our abiding purposes in our work — our students or our colleagues can help, too.

When we're at our best…

I heard it said recently that when we're at our best we ought to prepare for when we're at our worst. January, the month of resolutions and life-changey things, is often a month in which we're at our best. Before the month ends, schedule the time to create something — a Francis-esque credo, a Stuart-esque hand-scrawled chart paper — to remind Future You what in the world it was that you set out to do when the tougher months of February or May come along this year.

Footnotes:

- See this article re: bus.

- See this article re: feet.

- See this article re: doors.[hr]

Thank you to Nick Edwards, my brother, for putting me onto the great book Pope Francis: Why He Leads the Way He Leads.

John Yochum says

I so much enjoyed your article on reminder strategies, Dave.

davestuartjr says

John, every one of these goes out into the Internet with uncertainty that they’ll be worth a reader’s time. Thank you for assuring me that at least one reader benefited. Have a great day!

Ashley Bishop says

a simple and powerful activity. Thanks for being inspiring. I teach theatre, and so often the benefits of arts education get forgotten, or seem to fuzzy or magical to matter, but *I* know that the effects on students are meaningful. It’s hard to keep that in mind when you’re caught in the daily grind. I think this exercise will be beneficial to me *and* my students. Thank you.

davestuartjr says

Ashley, continue fighting for theatre. I see the theatre program in our school change student lives for the better every single year without fail. It’s a non-negotiable for great schools to have a program like yours.