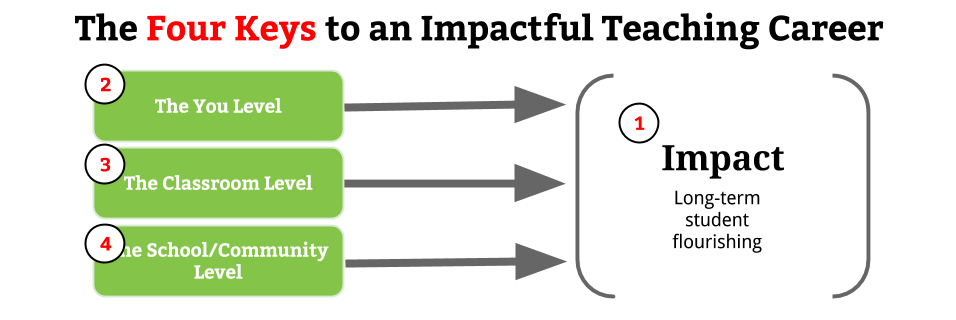

A lot of us educators got into this gig because we wanted to impact lives. Last post, I shared how I define impact. While some may have found it a bit too basic, I see no other way to begin seriously considering how to build an impactful career than by starting with the ultimate aim of teaching: the long-term flourishing of our students.

From there, we find our truest, simplest job description: as educators, our job is to promote the long-term flourishing of kids.

(Sorry, blame-mongers: I used the word “promote,” not “guarantee.”)

Thus, if I, as a teacher, can promote the long-term flourishing of a student, I go to bed at night content in the knowledge that I have had an impact on that kid's life. I may not be the next Ron Clark, but I'm fulfilling my calling to impact kids.

That's neat, Dave, but how do we actually do this?

So now is where the fun part comes in — this is the question we can dedicate our careers to: How in the world do we promote the long-term flourishing of our students? And how do we do so without becoming hopelessly demoralized by all the garbage? It's a constant battle — Steven Pressfield's The War of Art comes to mind — but such a worthy one.

I think the keys to building impactful careers are below:

In my last post, I discussed Key #1, which is simply the need to define what impact is. Now, let's get into the nitty gritty by looking at the first of three “levels” I think we need to strive within if we're to build an impactful career. It's worth noting that these levels build upon one another — meaning that today's post on “the you level” is actually more important than the next two posts on Classroom and School/Community levels.

Key #2: The You Level, or Jedi Mind Tricks for Avoiding Burnout

So here's what few teacher books will tell you — great teaching is only possible when your heart is in it, and yet there are so many factors seemingly bent on removing our hearts completely. Back when I started this blog, I considered standards one more group of things that were out to “get” us teachers, to rip out the heart of our profession.

And yet I now see that this need not be the case. When we approach standards like the Common Core with a “How can I wrangle this thing into something that promotes long-term student flourishing” attitude rather than a “Oh @#%& what now!?” attitude, the standards don't take our hearts out of the game and instead offer us a chance to learn a bit more about what it is we're after as teachers.

All of that is to say that the difference between my blog and a lot of “Common Core Aligned” resources/blogs out there is that I emphasize us, as educators, owning the standards and making sense of them so that they can inform (not deform) our literacy instruction. Likewise, the difference between teachers who maximize their impact long-term and those who get burnt out is that impactful teachers cultivate a mind bent on impact.

Cultivate is a key word — it brings up gardening imagery. Picture your mind/heart as a garden that needs constant tending, weeding, watering, fertilizing, and stuff like that. Gardening is a lot of work — that's why I'm horrible at it (see the photo above) — and so is keeping a heart and mind that can teach well.

The scary thing is that if we just let our hearts run on auto-pilot, we, like an ignored garden, will wake up one day to find that our internal selves are a hot mess.

Remember: No one gets into teaching hoping to one day burn out

As a new teacher, I used to look down on older, burnt out teachers until I realized that none of them, years ago with newly minted teaching certificates in their hands, dreamed of one day becoming burnt out gripemasters.

Have you ever realized that?

If you're like I was and you view the burnt out teachers in your building with disdain, you need to pause and accept the fact that they were once probably as passionate as you.

But, if you'd rather, you don't have to accept that. You can maintain an internal posture of “I'm better than them” (dig deep enough into your heart, and that's the attitude that's likely there, my friend). But I would caution you against that, as such attitudes are like the weeds that, left alone, will spread, sapping the life out of the parts of you from which great teaching flows.

Moving forward from that, I'd like to examine a few “Jedi mind tricks” that can help us to avoid burnout and maintain hearts and minds able to focus on having an impact.

Jedi Mind Trick #1: You are not your job

For the sake of the quality of your teaching, you need to accept something: you are not your job.

In other words, to keep my mind focused on impacting students, I have to pound into my head that the worth of Dave Stuart Jr. is not determined by how my students are scoring, how my evaluations are going, how well my students or colleagues like me, or anything else related to my job performance.

Intentionally seeking to mentally detach my self-worth from my job performance isn't only liberating professionally and personally, it's also downright empowering.

You see, when we allow our identity to become tied up with our job performance, two horrible things can happen.

Success!

If you don't take care to dissociate your core identity from your teacher identity, success is one of the worst things that can happen to you, and it will destroy you.

But Dave, you say, don't be so melodramatic! How can success wreck me?

When your job performance is linked, inside your head and heart, to your worth as a person, success will affect you like a narcotic. You will become proud; you will think you’re super-amazing. You will think you intrinsically merit greater attention than other teachers. You will expect to be honored frequently by the praise of others, and when others are praised instead of you, jealousy will sicken you like the stomach flu. You will look down on those who don't perform as well as you, and you will be prone to mocking them behind their backs, gossiping with delight. Not only these things, but you'll end up becoming so dependent upon success that you'll go to any length to achieve it, even if it costs you your family, your friendships, or your integrity.

My friend, you cannot build an impactful career when your identity is tied to your job performance because, when you inevitably do succeed, success will crush you.

Failure!

On the other hand, when you allow your teacher identity to become your whole identity, you'll start equating a bad day at school with a bad you. You'll start daydreaming about a career change; or you'll start lying about your failures, seeking to cover them up; or you'll simply start hating your students.

These are dark places — I do not write about them lightly, and I've struggled in many of them. There's no gain in lying about that.

But here's the good news: When your sense of self-worth is not rooted in your job performance, you are able to see your failures and shortcomings clearly. They cease to be personal, and they no longer threaten your being. This frees you to move onto Jedi Mind Trick #2.

Jedi Mind Trick #2: Embrace failure as progress

I can still remember how horrible I was as a student teacher. I was given a range of English language arts classes at Willow Run High School in Ypsilanti, Michigan. Like many student teachers, I was overflowing with ideas and enthusiasm; unlike many student teachers, I was in way over my head.

Quickly, I became overwhelmed with my failures. I couldn't manage my classroom, I couldn't get many kids to turn in their work, I couldn't get my kids to treat me or each other with respect, I couldn't get kids to consistently show up to class, I couldn't get things graded and returned to kids on time… .

To be blunt, I wasn't just riding the struggle train — I owned it.

To make it rougher, I was experiencing a debilitating mismatch between the successes I had envisioned during hours of educational theory classes leading up to student teaching and the reality of the daily failures I was facing. To make matters worse, I was a guy who, to some of my heroes growing up, had kind of become a disappointment by shifting my undergraduate focus from pre-medicine to teaching — so on top of everything else, I felt I had a lot to prove during this time of student teaching, and I clearly wasn't proving it.

My turning point began during an informal meeting of my student teaching cohort. It may or may not have been at The Brown Jug, one of my favorite undergrad hangouts in Ann Arbor. We were sitting there, “enjoying” our pints of Miller Lite or something equally classy, and I was recounting another day of failures to my friends. I ended my depressed monologue with something like, “But, I guess the bright side is every time I fail, I learn what doesn't work.”

My friends, happy that I was done droning on, moved the conversation in another direction, but I just sat there, dumbstruck, at the wisdom I had just stumbled upon.

(This doesn't happen often, I promise.)

It was as if lightning had struck my proverbial, storm-tormented kite — I had made a pivotal discovery.

Whenever something I try in the classroom fails, at least one person gets better/stronger/smarter: me.

In short, failure = progress.

This became a nuclear power plant for my teaching. I went from the guy who fails mopingly to the guy who fails excitedly because of the lessons I was learning. It turned my worst days into some of my most productive; days in which my greatest weaknesses were laid bare like those nightmares where you realized you're not wearing pants became days in which my strength as a teacher grew the most.

As a result, I began growing what Angela Duckworth would later dub “grit”. I began engaging in the deliberate practice — practice focused on areas within a skillset where one is weak — of which, according to K. Anders Ericsson, one needs 10,000 hours of to attain skill at an international level.

My experience level began increasing exponentially. I was learning in one day of productive failure what it took some in my cohort a week to learn. In a week, I was gaining a month of experience. By the end of my student teaching, I was far from truly ready for my first year, but I was a markedly different teacher from the dejected shadow who couldn't cope with not being good enough.

I share this story with you not to brag, but in the hope that you, too, can become someone who sees failure as the opportunity it is.

Jedi Mind Trick #3: Our goal is impact, not popularity

One of the most common traps I see teachers (including me) fall into is getting addicted to being liked. Every day we have these captive audiences (our students), and it's so easy to start to relish their “You're my favorite teacher”-type comments or notes.

And here's the tricky thing: we do need them to hold some kind of positive feeling toward us — we need them to respect us or admire us or enjoy us — if we're to maximally impact them. I don't have any hard evidence for that, but in reflecting on my own life, it's the people who I admired or respected (even if it was a begrudging respect) who I learned the most from.

So we need them to like/respect us, and yet I'm telling you that you cannot make this your end goal. It may sound contradictory, but it's true.

Here's my reasoning: if your identity depends on the appreciation of students (Or colleagues. Or parents. Or bosses.), you will struggle to make the right calls in tough situations.

Here's an example of what I'm talking about.

Belle's story

I had a student a couple years back who I'll call Belle. Belle had always been super-aloof toward me. I can still remember how she would look at me when I'd attempt a joke or when I'd show my passion to my students: it was a look that said, “You are some kind of alien life-form. You do not smell good. It is unpleasant to be in the same building as you.” We're talking a look, and Belle had it perfected.

About midway through the year, I pulled Belle into the hall for a mini-conference — I like to do this with each student in turn when my whole class is focused on independently reading or writing — and I asked her how school was going.

“Fine,” she said, face overflowing with the look.

“What are your grades right now?” I responded.

She listed off a few letters for her different classes; a few were failing, and none were stellar. She was oozing with apathy, waiting to hear my response.

*PAUSE*

This is where I was faced with a tough situation. What could I say to Belle to help her experience more success in school? I knew she had some intensely hard things going on at home. I knew she had some friend drama at school. I was pretty sure she couldn't care less about me as a human. Could this be my chance to win her over with some nice, soft words?

I didn't have time to think through all these things — she needed a response now. And this is why we have to cultivate our hearts — in moments like these, when there's no time for calculation, the basic orientation of our hearts comes forth from our lips; these tiny teacher decisions flow from who we are, so we have to do the work of making sure we are something worth flowing.

*UNPAUSE*

“Belle,” I said, looking her straight in the eyes, “if those are your grades, then school is not going fine.”

In that moment, I was not speaking from anger or annoyance — just concern. I wanted Belle to have a chance at a flourishing life, and I knew if she kept on the course she was, she'd leave high school severely handicapped. Unfortunately, job applications don't ask you to write down the difficult home situation that leads you to graduate high school with a skill deficit; therefore I, as a high school teacher, have to be honest with kids about the unpleasant need to learn how to grapple with sometimes wretched home environments and still manage school.

I told Belle as much and patted her on the shoulder as she walked back into the classroom, letting her know I was in her corner and willing to help her figure out how to better handle her course load.

She went back in, sat down, did her work, left my class, and later that day, got suspended from school for getting into a fight.

Dave Stuart Jr. for the impact win.

When my principal came up to my room to tell me that Belle had been in a fight, my head raced with self-accusation.

Nice job, moron, I thought. You demoralized the kid. Solid.

But then my principal went on to say how, sitting in the principal's office after the fight, Belle had broken down and poured out her heartbreaking home situation. The principal asked Belle if she had anyone at all she felt she could talk to at school to help her manage so much junk.

Belle nodded, saying, “Yeah, I've got Mr. Stuart.”

The moral of the story is that, had I not given Belle the truth during our hallway mini-conference — had I instead responded with something I hoped would boost her self-esteem or make her like me — I doubt she would have thought of me as someone she could go to.

My goal is not to be the messiah of my students — it is to impact them. For the rest of the year, I was able to use my increased influence with Belle to help her grow in her literacy skills, simply because I made the right call in the tough situation.

Seek their good, not their approval

I'm not saying be a jerk to kids — I am saying you've got to have higher goals than to simply have them love you. Interestingly enough, since I've started to embrace this, I've found that I am more liked by students, not less.

I know that in our day of student-centered ideology — which doesn't mean treating adolescents with kid gloves, I'd argue — I'm giving a potentially unfashionable message, but the reality is that I frequently tell students in private and in public that their performance is unacceptable and that they are capable of much more. As a teacher, I am now horrified of doing my students the disservice of falsely inflating them; instead, I want my students rooted in reality. If Bobby can write a great short story about hunting but cannot submit work on time or present himself to others in a considerate manner, I want to be a teacher who tells him, “Here's why your short story is great, and here's why your life is still on a path to frustration, whether you're a great writer or not.”

Forgive me if that sounds jacked up, but please, come to my classroom someday and see what I am talking about — kids are dying to be taken seriously.

Jedi Mind Trick #4: Teaching can build your character

The final “Jedi mind trick” you can use to help cultivate a mind focused on impacting students is to remember that hardship builds character. I know this sounds like something a cigar-smoking grandpa might say, but if we embrace it, it is so true: challenging situations (like those teaching constantly assails us with) are a refining, smelting furnace for character strengths (which I've written above elsewhere on the blog).

[Editor's Note from Dave: I no longer stress character strengths in my classroom. Now, I seek to cultivate the five key beliefs, trusting that the strengths will develop as kids do work with care.]

One of the key strategies I have for helping my students develop the character strengths described in Paul Tough's How Children Succeed is simple: I want to authentically pursue the character strengths in myself, right in front of them. To put it negatively, I cannot best help my students develop highly predictive character strengths if I don't first exemplify the strengths myself.

This means when teacher times get tough, remind yourself that failure is not just a place within which you can grow your teacher craft, it's also a place in which you can grow your character.

What do you think?

Did I miss anything? What things do you try to keep in mind when it comes to cultivating a mind and heart from which you can best teach? Or is this all hogwash, and I just need to hurry up and get to the good stuff? Let me know in the comments

Mary says

This is great!

Ted Morrissey says

A lot of great points (please proofread before I share — happens to us all).

davestuartjr says

Hi Ted, I’m not sure what you mean — proofread before you share what?

caragregory says

This is so thoughtful…and it speaks directly to my experience. I have made my career a defining aspect of who am I. Since I’m “successful,” I can get snarky about teachers who “make posters all day”. Also, they are the ones who seem to think telling the truth about educational attainment is being mean…they are on the hunt for friends, not students. I am going to take your advice and see my room as my garden and the rest of the school as the block with other people’s houses. I wouldn’t go paint my neighbor’s house. Your latest posts have helped my soul and certainly given me food for thought. MAJOR PROPS!

davestuartjr says

Cara, I’m so glad these posts have been worthwhile — I know this blog started solely as a study of the Common Core literacy standards, but this topic is one of my favorite to talk about. There is such richness in the interior aspects of teaching — lots of fun to write and think about.

Thank you so much, Cara, for sharing that these posts have helped your soul out a bit — that is very humble of you Warmest regards!

Warmest regards!

Dulcy says

I love your Mind trick #3. Students, like all humans, just want to know that they matter, that someone cares enough about them to say the “real” stuff. My high school students are experts at detecting if someone genuinely cares for them.

Thanks, Dave.

davestuartjr says

Dulcy, thank you for taking the time to share. May we be more and more genuine in our love for students.

Shelly says

Dave–I had a significant experience of realizing I still had a little bit of identity tied up in my work performance. So grateful for my friends and family that repeatedly told me that that flop was not me. This post is right on target. Thanks for the reminder!

Dani says

I think Ted meant you should proofread your material before you share it. It was good but there were quite a few spelling errors.

davestuartjr says

Thank you Dani — I think you are right. I went back through yesterday and weeded out a lot of the mess-ups, I think.

I think I’m going to put an ad on Craigslist: Wanted — Live-in proofreader. You proofread my entire blog, I let you live in my basement with free room and board.

Creepy? Maybe. Desperate times call for desperate measures, though!

Chad Walden says

Dave, you are a wise and generous dude. Thanks for sharing another insightful post, and congrats on the birth of your daughter.

davestuartjr says

Thank you Chad and thank you also for your shout-out on Twitter. Warm regards to you and your family.

Chris B says

Thanks for this post. I am thoroughly convinced that our goal should be to help students flourish long term, which is why grit is so important. Most of life’s truly meaningful moments are built around stuff that is not so pleasant. Critical thinking is hard work. Facing down our mistakes, misdeeds, and ignorance is scary. Negotiating new ideas with our already comfortable and jam packed schema of the world is confusing. Opening ourselves up to criticism can be painful. But all of these things can also lead to a more enlightened, more meaningful, and more joyful life experience, and can be more easily endured when we are working for what we consider a higher purpose. I’ve read a lot of your stuff, but I am interested in anything you have about being purposeful and helping your students engage in a higher purpose. Something that is good and important and meaningful. On personal reflection the only moment I ever cared about learning skills was when I had a very specific and more elevated purpose in mind. I could have cared less about grammar until I started to understand how it helps me communicate things that are important to me (etc). I know you gave time to your students to work independently on something that would impact the world. Any insights from that? I kind of think I would want to try something smaller, but am waiting to hear more.

davestuartjr says

Chris, what a phenomenal post idea. I, like you, am most engaged when I keep the long-term (or higher) purpose in mind, and my students are no different. I think a big part of a great teaching is this ability to cast vision for our kids. I discuss it a bit in my post on sports metaphors (the “team” ethos in my room is one angle I take to build student consciousness around our higher purpose as a class).

What you get at is that our job as teachers is to be professional explainers — but our job isn’t just to explain the “what” (e.g., the grammar and mechanics) but, just as importantly because it’s where engagement lies, the “why.”

The project you’re mentioning is, I think, the Charity: Water one, correct? I used the students’ new knowledge about the water crisis to connect with themes I hit on all year (that becoming literate at the college/career ready level makes us more able to impact the world later on).

Lynsay says

It’s always been counter-intuitive for me that the moment you disconnect your self-worth from your job is the moment you have the capacity to do your job better than you ever have before. When I do this, I have fewer emotional highs and lows, and I get to spend all that reserved energy actually improving instructional outcomes for kids. Thanks for the reminder.

davestuartjr says

My pleasure, Lynsay

sarakershaw says

I really loved Jedi Mind Trick #3. I am our school’s NHS sponsor, and every year in May we have an NHS awards banquet. Graduating members are honored individually, and I have them fill out a questionnaire before the ceremony so I have things to read as they come forward. The most interesting part of each student’s information is always their answer to this question: Which teacher has made the greatest impact on you and why? It’s a loaded question, and the students involved are often the students that are most invented in their own educations. Every once in a while, one of the “fun” teachers makes the list somewhere, but invariably the teachers that students list are the teachers that students respect the most as educators. Their classes are difficult and demanding. They assign homework during break. They are brave enough to accept getting complained about regularly. Every year, I make it my goal to strive to be more and more like these teachers. It’s not a popularity contest. Beautifully put.

Thank you.

davestuartjr says

Yes, Sara — exactly! And it is these kids who we often forsake when we fall into the popularity contest trap. I am with you, striving to be more like those teachers. Beautifully put yourself, miss.

Amber says

I recently began my third year of teaching, and I desperately needed to read this (and the previous) post. I have been well on my way to a burn out. I have a crazy load and no time to think and remember some of the things you wrote about here.

Funny/sad story, though: I’ve been the young, fresh-out-of-college teacher. Last year, everyone would say, “You’re my favorite teacher! I just love your class!” I ate it up! I loved it!! Then, one day, I was accidentally eavesdropping on some of their conversations, and they were discussing their classes and what not. One of my students said, “Oh, I love this class! We never really do anything.” WHAT?! I was shocked. I feel like we are always doing something!! I carry home stacks of papers and grade through the night!! It turns out the particular kid was failing my class because HE never did anything, but I was definitely teaching. Either way, it was a sad realization and a major blow to my teacher self-esteem, but I learned that being the favorite isn’t always a good thing. Ha! Talk about a humbling experience!

davestuartjr says

Amber, I had a few nearly identical experiences — I am so thankful for them, too, because they called me to higher ground. I needed to do more than get them to like me; I needed to impact their lives — and I was falling short of that and not even realizing it because I was drinking up their “favorite teacher” comments.

I can say now that the addiction to that “drink” does go away. I feel like I actually dislike hearing it now — I’d much rather know I’ve impacted the kid and promoted his/her long-term flourishing.

Thank God for humbling experiences like the one you describe — and thank you, Amber, for sharing this!

rachelwasserman2013 Wasserman says

Dear Dave: This is “Rachel from Arizona” — I’m the one who felt so hopeless and discouraged last summer. Thanks in part to your blog, I’ve rebounded. I’d like to address your vital point that basing one’s self-esteem and mental health totally on one’s job can be disastrous. I fell into that trap and remained stuck in a pretty negative place for more years than I care to remember. When students liked me, and expressed their liking, I was elated. When I was singled out for praise at a faculty meeting or got a terrific performance evaluation, I was thrilled. But this was a pitfall that encouraged my self-esteem to bounce up and down like a yo-yo. I was envious when other teachers were singled out for praise, and at times became bitter and resentful, and when I encountered kids who openly disliked me I felt hurt and betrayed — all the things you’ve discussed.

It is truly difficult to get to a point where external elements can be regarded primarily as signposts on our own road to self-knowledge and improvement — and I don’t know that I’ll ever truly reach that goal. Meanwhile, the journey continues.

I would like to say that as a department chair, I see it as my job to reassure both new and veteran teachers that teaching is an art and a process — and that all thoughtful teachers experience enormous emotional ups and downs. I see my job as helping them weather these events. But it is hard, and getting harder. Our district now publishes (in our only local daily newspaper) our teacher evaluations, without comment. And this “final” published review now includes how our students did on several state-mandated standardized tests. In reality, this means that a teacher who scored a 95% out of a possible 100 points on an observational performance review may see his “score” go down 30 or more points if his students did not do well on these tests. The public often sees this as a tool to identify a bad teacher.

While I totally support national common standards and standardized tests, I feel so closely linking our classroom performance to these test scores is analogous to giving my personal physician a terrible rating because I’m overweight. After all, if my doctor were really good at her job, she would have convinced me to skip the Ben & Jerry’s in favor of a celery stick.

There are so many factors influencing how a child does on these tests; from a fight with a parent the night before to no breakfast that morning, not forgetting that a number of high school students are coming into classes with elementary-level skills.

Many of us work hard at remediating our kids’ learning deficits, but few of us have magic wands that allow students to gain years’ worth of knowledge and skills in a few months. There must be a better way to evaluate our performance rather than linking it so tightly to testing — but what that method might be is still unclear. I would welcome your thoughts on this.

davestuartjr says

Rachel! Awesome to hear from you! That was one of my favorite posts from last summer.

Wow — you live in a place that I’ve heard warned about by my teaching colleagues but always assumed would not actually happen. I can’t believe they actually do the newspaper thing — that being a real thing makes me feel we have definitely entered some form of alternate universe.

At the end of the day, we cannot make a child own his or her education — all we can do is strive to get better and better and helping kids to own their learning and, ultimately, the lives they need to be building toward in school.

Analyzing student achievement results is one piece of the puzzle for evaluating us — the problem is that where it’s logical to evaluate me on how well I do at teaching kids to write a 9th grade appropriate paper, it becomes significantly less logical to evaluate me for how they do on a test in May that may measure things they learned in September. “One and done,” high-stakes tests are a pretty cheap way to pretend that we’re holding teachers accountable — but it’s really just pretending.

If and when my town paper starts doing what yours has, I, too, will look like a fool and will likely be thought a poor teacher. There are kids I don’t reach every year, despite my best efforts; there are skill gaps my courses do not adequately remedy.

At the end of the day, we just keep doing the work of separating our identity from how people view us. I care about what I know are my teaching deficiencies — not what a high-stakes, poorly conceived test tells me.

Thank you Rachel from Arizona Keep in touch.

Keep in touch.

Melanie says

As a first year teacher, I related to everything that you wrote in this. I will be rereading this in the weeks and months ahead! Thank you for the eye-opening advice, Dave.

Mike White says

21 years into teaching, and I’m positively glad I’ve read this particular blog! I have walked the hall of my current school feeling like quite the failure for not impacting the students more successfully. Failure as progress and removing my self-esteem from the mix are two states of mind that will help me improve overall as a teacher. Thank you! Now, back to NFO Guide to Teaching Common Core. Have a day!!

davestuartjr says

Mike, it has been a pleasure reading your comments over the past month — I hope the book is helpful. Remember to read These Five Things All Year Long (www.davestuartjr.com/five) — it’s a more updated take on how to feasibly treat the CCSS without going bonkers.

Cheers, Mike.

Carmen Munnelly says

My brother, this is stuff I wish I’d heard before I walked into my first day of student teaching. Before I found out how BORRING was my Romeo & Juliet unit. Before I said “yes” to tons of committees to impress bosses (instead of saying “yes” to help improve the school. Before I ever felt consumed by this vocation. Before I felt slighted unless I was a favorite.

“Cheap prizes…” how true.

After 25 years, reading your messages have been a kind of emotional chiropractic for my teaching goals. Thanks, Doc.

davestuartjr says

My sister, thank YOU! This is balm for a blogger’s soul. Thank you for your kindness toward me in writing this.

Austin M. says

Hi Dave,

Just recently found your blog and it’s been a great couple of days going through it. I’m in year two of teaching HS English, and I find this early on in teaching (and later) you just have to embrace the failures.

I look forward to another school year here in southeast Michigan.

Thanks man,

Austin

B Butler says

I couldn’t agree with you more that teaching builds our own character. I have had the most difficult group of students (several ‘Belles’) and I am learning so much about MYSELF through this experience. I’m learning that hard lesson that I might not be the favorite teacher, but I am working hard to be the reliable, truth-telling teacher. It’s a fine balance. Thank you for your honesty, humor, and wisdom.

Dave Stuart Jr. says

“The reliable, truth-telling teacher” — me too, Barb. Cheers to you in this work.