I've never met a teacher who didn't go into education hoping that they'd make a difference — that, ultimately, their work would promote the long-term flourishing of young people. There's no other way to begin talking about burnout than by starting with the ultimate aim of teaching: the long-term flourishing of our students.

From there, we find our truest, simplest job description: as educators, our job is to promote the long-term flourishing of kids.

(Please note: promote doesn't mean guarantee.)

We do this through teaching kids what we're assigned to teach them.

Thus, if I, as a teacher, can promote the long-term flourishing of a student, I can go to bed at night content in the knowledge that I have had an impact on that kid's life. I may not be the next Ron Clark, but I'm fulfilling my calling and doing the core of my job.

That's neat, Dave, but how do we actually do this?

So now is where the fun part comes in — this is the question we can dedicate our careers to: How in the world do we promote the long-term flourishing of our students? And how do we do so without becoming hopelessly demoralized by all the garbage? It's a constant battle — Steven Pressfield's The War of Art comes to mind — but such a worthy one.

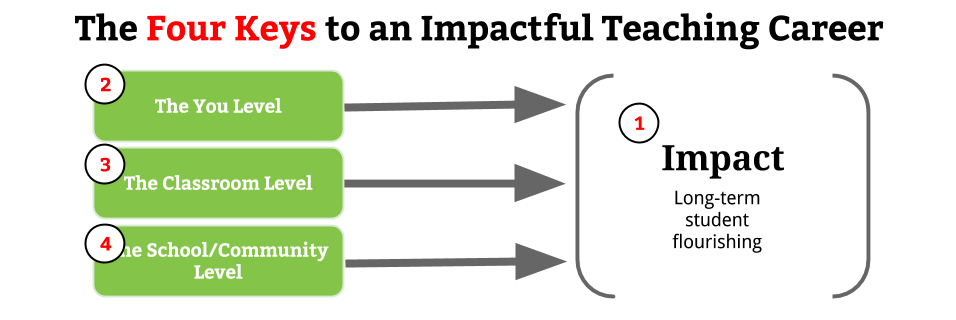

I think the keys to building impactful careers are below:

- You've got to know what you're ultimately after, no matter the class you're assigned or the kids you have on your roster this year.

- You've got to become good at the internal work of teaching.

- You've got to take care of business in the classroom.

- You've got to work well with adults.

You can be a decent teacher for a little while while ignoring some of these areas, but if you're going to flourish long-term, there's no permanently skipping any of these. (Talking to you, teacher who says, “I love the kids in teaching, I just hate the adults.” With love.) Today, I'm going to focus on the second part: You.

The You Level; or Jedi Mind Tricks for Avoiding Burnout

So here's what few teacher books will tell you: great teaching is only possible when you are engaged with it with your mind and heart and soul, but this is hard because it's almost like present conditions were designed to rip out our hearts and drive us out of our minds and detach our souls. But our perception of present circumstances is malleable.

For example, waaay back when I started this blog, it was called Teaching the Core, and it was me writing my way through understanding the Common Core literacy standards. I just wanted to understand them because, up to that point, I had considered minutiae-filled standards to be one more thing that was out to drive us insane and rip out the heart of our profession.

And yet I quickly found that the standards didn't have to be that way. When we approach standards like the Common Core with a “How can I wrangle these things into something that promotes long-term student flourishing?” attitude rather than an “Oh @#%&, what now!?” attitude, the standards don't crush us. Instead, they offer us a chance to learn a bit more about what it is we're after as teachers.

All of that is to say that the difference between my blog back then and a lot of “Common Core Aligned” resources/blogs out there was that I emphasized us, as educators, owning the standards and making sense of them so that they might inform (rather than deform) our literacy instruction. Likewise, the difference between teachers who maximize their impact long-term and those who get burnt out is that impactful teachers cultivate a mind bent on impact. That's my point.

Cultivate is a key word — it brings up gardening imagery. Picture your mind/heart as a garden that needs constant tending, weeding, watering, fertilizing, and stuff like that. Gardening is a lot of work (I've heard), and so is keeping a heart and mind that can teach well (I know).

Cultivate is a key word — it brings up gardening imagery. Picture your mind/heart as a garden that needs constant tending, weeding, watering, fertilizing, and stuff like that. Gardening is a lot of work (I've heard), and so is keeping a heart and mind that can teach well (I know).

The scary thing is that if we just let our hearts run on auto-pilot, we, like an ignored garden, will wake up one day to find that our internal selves are a hot mess.

Remember: No one gets into teaching hoping to one day burn out

As a new teacher, I used to look down on older, burnt out teachers until I realized that none of them, years ago with newly minted teaching certificates in their hands, dreamed of one day becoming burnt out gripe-masters.

Have you ever realized that?

If you're like I was and you view the burnt out teachers in your building with disdain, you need to pause and accept the fact that they were once as passionate and smart and full of ideas as you.

But, if you'd rather, you don't have to accept that. You can maintain an internal posture of “I'm better than them” (dig deep enough into your heart, and that's the only other attitude that can be there, my friend). But I would caution you against that, as such attitudes are like the weeds that, left alone, will spread, sapping the life out of the place where great teaching comes from.

Moving forward from that, I'd like to examine a few “Jedi mind tricks” that can help us to avoid burnout and maintain hearts and minds able to focus on having an impact.

Jedi Mind Trick #1: You are not your job.

For the sake of the quality of your teaching, you need to accept something: you are not your job.

In other words, to keep my mind focused on impacting students, I have to pound into my head that the worth of Dave Stuart Jr. is not determined by how my students are scoring, how my evaluations are going, how well my students or colleagues like me, or anything else related to my job performance.

This is intentionally working to detach my self-worth from my job performance. It isn't only liberating professionally and personally — it's empowering.

You see, when we allow our identity to become tied up with our job performance, two horrible things can happen.

Success!

If you don't take care to dissociate your core identity from your teacher identity, success is one of the worst things that can happen to you, and it will destroy you.

But Dave, you say, don't be so melodramatic! How can success wreck me?

When your job performance is linked, inside your head and heart, to your worth as a person, success will affect you like a narcotic. You will become proud; you will think you’re super amazing, God's gift to the profession. You will think you intrinsically merit greater attention than other teachers. You will expect to be honored frequently by the praise of others, and when others are praised instead of you, jealousy will sicken you like the stomach flu. You will look down on those who don't perform as well as you, and you will be prone to mocking them behind their backs, gossiping with delight. Not only these things, but you'll end up becoming so dependent upon success that you'll go to any length to achieve it, even if it costs you your family, your friendships, or your integrity.

My friend, you cannot build an impactful career when your identity is tied to your job performance because when you inevitably do succeed, success will crush you.

Failure!

On the other hand, when you allow your teacher identity to become your whole identity, you'll start equating a bad day at school with a bad you. You'll start daydreaming about a career change, or you'll start lying about your failures, seeking to cover them up, or you'll simply start hating your students.

These are dark places — I do not write about them lightly, and I've struggled in many of them. There's no gain in lying about that.

But here's the good news: When your sense of self-worth is not rooted in your job performance, you are able to see your failures and shortcomings clearly. They cease to be personal, and they no longer threaten your being. This frees you to move onto Jedi Mind Trick #2.

Jedi Mind Trick #2: Embrace failure as progress

I can still remember how horrible I was as a student teacher. I was given a range of English language arts classes at Willow Run High School in Ypsilanti, Michigan. Like many student teachers, I was overflowing with ideas and enthusiasm; unlike many student teachers, I was in way over my head.

Quickly, I became overwhelmed with my failures. I couldn't manage my classroom, I couldn't get many kids to turn in their work, I couldn't get my students to treat me or each other with respect, I couldn't get kids to consistently show up to class, I couldn't get things graded and returned to kids on time…

To be blunt, I wasn't just riding the struggle train — I conducted it.

To make it rougher, I was experiencing a debilitating mismatch between the successes I had envisioned during hours of educational theory classes leading up to student teaching and the reality of the daily failures I was facing. To make matters worse, I was a guy who, to some of my heroes growing up, had kind of become a disappointment by shifting my undergraduate focus from pre-medicine to teaching — so on top of everything else, I felt I had a lot to prove during this time of student teaching, and I clearly wasn't proving it.

My turning point began during an informal meeting of my student teaching cohort. It may or may not have been at The Brown Jug, one of my favorite undergrad hangouts in Ann Arbor. We were sitting there, “enjoying” our pints of Miller Lite, and I was recounting another day of failures to my friends. I ended my depressed monologue with something like, “But, I guess the bright side is every time I fail, I learn what doesn't work.”

My companions, happy that I was done droning on, moved the conversation in another direction, but I just sat there, dumbstruck, at the wisdom I had just stumbled upon.

(This doesn't happen often, I promise.)

It was as if lightning had struck my proverbial, storm-tormented kite — I had made a pivotal discovery.

Whenever something I try in the classroom fails, at least one person gets better/stronger/smarter: me.

In short, failure = progress.

This became a nuclear reactor for my teaching. I went from the guy who fails mopingly to the guy who fails excitedly because of the lessons I was learning. It turned my worst days into some of my most productive; days in which my greatest weaknesses were laid bare like those nightmares where you realize you're not wearing any pants became days in which my strength as a teacher grew the most.

As a result, I began growing what Angela Duckworth would later dub “grit.” I began engaging in the deliberate practice — practice focused on areas within a skillset where one is weak — of which, according to K. Anders Ericsson, one needs 10,000 hours in order attain skill at an international level.

My experience level began increasing exponentially. I was learning in one day of productive failure what it took some in my cohort a week to learn. In a week, I was gaining a month of experience. By the end of my student teaching, I was far from truly ready for my first year, but I was a markedly different teacher from the dejected shadow who couldn't cope with not being good enough.

I share this story with you not to brag, but in the hope that you, too, can become someone who sees failure as the opportunity it is.

Jedi Mind Trick #3: Our goal is impact, not popularity

One of the most common traps I see teachers (including me) fall into is getting addicted to being liked. Every day we have these captive audiences (our students), and it's so easy to start to relish their “You're my favorite teacher”-type comments or notes.

And here's the tricky thing: we do need them to hold some kind of positive feeling toward us — we need them to respect us or admire us or enjoy us — if we're to maximally impact them. Teacher credibility is an idea vetted in the research and in our own common sense. As I reflect on my own life, it's the people who I admired or respected (even if it was a begrudging respect) who I learned the most from.

So we need them to like/respect us, and yet I'm telling you that you cannot make this your end goal. It may sound contradictory, but it's true.

Here's my reasoning: if your identity depends on the appreciation of students (or colleagues, or parents, or bosses) you will struggle to make the right calls in tough situations.

Here's an example of what I'm talking about.

Belle's story

I had a student a couple years back who I'll call Belle. Belle had always been super-aloof toward me. I can still remember how she would look at me when I'd attempt a joke or when I'd show my passion to my students: it was a look that said, “You are some kind of alien life form. You do not smell good. It is unpleasant to be in the same building as you.” We're talking a look, and Belle had it perfected.

About midway through the year, I pulled Belle into the hall for a mini-conference — I like to do this with each student in turn when my whole class is focused on independently reading or writing — and I asked her how school was going.

“Fine,” she said, face overflowing with the look.

“What are your grades right now?” I responded.

She listed off a few letters for her different classes; a few were failing, and none were stellar. She was oozing with apathy, waiting to hear my response.

[box border=”full” icon=”none”]*PAUSE*

This is where I was faced with a tough situation. What could I say to Belle to help her experience more success in school? I knew she had some intensely hard things going on at home. I knew she had some friend drama at school. I was pretty sure she couldn't care less about me as a human. Could this be my chance to win her over with some nice, soft words?

I didn't have time to think through all these things — she needed a response now. And this is why we have to cultivate our hearts — in moments like these, when there's no time for calculation, the basic orientation of our hearts comes forth from our lips; these tiny teacher decisions flow from who we are, so we have to do the work of making sure we are something worth flowing.

*UNPAUSE*[/box]

“Belle,” I said, looking her straight in the eyes, “if those are your grades, then school is not going fine.”

In that moment, I was not speaking from anger or annoyance — just concern. I wanted Belle to have a chance at a flourishing life, and I knew if she kept on this course, she'd leave high school severely handicapped. Unfortunately, job applications don't ask you to write down the difficult home situation that led you to graduate high school with a skill deficit; therefore I, as a high school teacher, have to be honest with kids about the unpleasant need to learn how to grapple with sometimes wretched home environments and still manage school.

I told Belle as much and patted her on the shoulder as she walked back into the classroom, letting her know I was in her corner and willing to help her figure out how to better handle her course load.

She went back in, sat down, did her work, left my class, and later that day, got suspended from school for getting into a fight.

Dave Stuart Jr. for the impact win.

When my principal came up to my room to tell me that Belle had been in a fight, my head raced with self-accusation.

Nice job, moron, I thought. You demoralized the kid. Solid.

But then my principal went on to say how, sitting in the principal's office after the fight, Belle had broken down and poured out her heartbreaking home situation. The principal asked Belle if she had anyone at all she felt she could talk to at school to help her manage so much junk.

Belle nodded, saying, “Yeah, I've got Mr. Stuart.”

The moral of the story is that, had I not given Belle the truth during our hallway mini-conference — had I instead responded with something I hoped would boost her self-esteem or make her like me — I doubt she would have thought of me as someone she could go to.

My goal is not to be the messiah of my students — it is to impact them. For the rest of the year, I was able to use my increased influence with Belle to help her grow in her literacy skills, simply because I made the right call in the tough situation.

Seek their good, not their approval

I'm not saying be a jerk to kids — I am saying you've got to have higher goals than to simply have them love you. Them loving you makes you popular, but not necessarily a good teacher.

(Interestingly enough, since I've started to embrace this, I've found that I am more liked by far more students, not less.)

I know that in our day of student-centered ideology — which doesn't mean treating adolescents with kid gloves, I'd argue — I'm giving a potentially unfashionable message, but the reality is that I frequently tell students in private and in public that their performance is unacceptable and that they are capable of much more. As a teacher, I am now horrified of doing my students the disservice of falsely inflating them; instead, I want my students rooted in reality. If Bobby can write a great short story about hunting but cannot submit work on time or present himself to others in a considerate manner, I want to be a teacher who tells him, “Here's why your short story is great, and here's why your life is still on a path to frustration, whether you're a great writer or not.”

Forgive me if that sounds jacked up, but please, come to my classroom someday. You'll see what I am talking about. Kids are dying to be taken seriously.

Jedi Mind Trick #4: Teaching can build your character

The final “Jedi mind trick” you can use to help cultivate a mind focused on impacting students is to remember that hardship builds character. I know this sounds like something a cigar-smoking grandpa might say, but if we embrace it, it is so true: challenging situations (like those teaching constantly assails us with) are a refining, smelting furnace for things like patience, kindness, gentleness, self-control, gratitude, social intelligence, and so much more. These are the kinds of things we want to be known for — things that David Brooks calls “eulogy virtues.”

One of the key strategies I have for helping my students develop the character strengths described in Paul Tough's How Children Succeed is simple: I want to authentically pursue the character strengths in myself, right in front of them. To put it negatively, I cannot best help my students develop highly predictive character strengths if I don't first exemplify the strengths myself.

(I used to write a lot about character strengths on my blog, and I used to have a list of them posted on my classroom wall. I'm now more convinced that these strengths are a byproduct of doing good and challenging work. And so instead of targeting the strengths explicitly with my students, I work hard at cultivating the five beliefs that make my students do work with care.)

This means when teacher times get tough, remind yourself that failure is not just a place within which you can grow your teacher craft, it's also a place in which you can grow your character.

What do you think?

Did I miss anything? What things do you try to keep in mind when it comes to cultivating a mind and heart from which you can best teach? Or is this all hogwash, and I just need to hurry up and get to the good stuff? Let me know in the comments. 🙂

patrycja says

Yet another great article, Dave. I think I remember reading this some time ago, but it’s always good to re-read as a reminder. I especially like how you point out teachers are NOT their jobs! Distinguishing our identities is so important to staying professional and healthy. I also appreciate your honesty about teacher jealousy. Comparison is yet another often overlooked factor in burnout. Thanks again.

davestuartjr says

Patrycja, you are so right — comparison kills joy.

Amy Treadwell says

That made me cry. Wow. I need to re read it and determine how to apply this to my own world working with teachers and students. VERY grateful for this post and all of the others. Thank you.

Taryn McGready says

I am relieved to know that I’m not the only one who reads Dave Stuart’s blog and cries! 🙂 This is one of my favorites.

davestuartjr says

Taryn and Amy, thank you for taking the time and the care. I’m grateful for both of you.

Jenny Johansen says

Love this! Kids / teenagers are dying to be taken seriously, and that means showing respect and speaking honestly with care. Guiding, encouraging, challenging, expecting, scaffolding, …. I try to do these things always with respect and care for students. Your words are very encouraging – again! Thank you

davestuartjr says

I’m so glad, Jenny — and your words are too. Thank you my colleague.

Carolyn Moore says

I work with Induction teachers, and this was dead-on. I needed some of the reminders. Thank you.

davestuartjr says

Carolyn, I am so glad. Your work is CRITICAL. Keep after it my colleague.

Ann Headrick says

Great blog! Another one to save and reflect on! Thanks for helping teachers keep things in perspective!

davestuartjr says

Thank you, Ann! I hope you are well there in Arkansas City 🙂

Ica Rewitz says

I love this, and I appreciate the time it took to lay this out. I guess where I am stuck is what are some things I can actually DO that will help? Trick # 1 – You are not your job. Great! I think I believe this, most of the time, and yet it still feels REALLY crappy when my students aren’t getting their work done (classroom management, I know) or I am talking to a kid for 12th and 13th time this year about the importance of doing their independent reading, and they STILL won’t pick up a book outside of my classroom. I’m sitting here on a Saturday, and what can I DO (other than the grading and planning that I’m about to do) that would make a difference in my stress level or my feelings of burn out next week?

davestuartjr says

Ica, great question. I’ve struggled with live groups making Trick #1 practical. I do think it might be as simple as taking a walk, or reading a book that’s totally unrelated to teaching. Identity I think is a lot about proving to ourselves what kind of person we are. And so when we spend too much time on teaching outside of our working hours, it makes it hard to not take those problems you describe as indications of us being *personally* lacking v. as indications that we still have interesting problems we’re working to solve.

So: go take a walk, right now 🙂

Ica Rewitz says

Thanks so much, Dave. I cannot tell you how much I appreciate your work and everything you share with us.