If current events are only being studied and discussed in one class during the school day — say, in your school's English classes, where you're having kids read and respond to an Article of the Week a la Kelly Gallagher; or it's in your high school's Current Events elective — then kids won't graduate as smart about the present world as we need them to be. In order to understand things like US politics, global climate, the rise of automation, or the North Korea security and humanitarian crises, you need to know a lot of things, and such robust knowledge-building can’t happen in a single course or department. I don’t care how many times you talk to kids about critical thinking or how many times you have them argue or pop-up debate on the topics I just mentioned. Kids (and adults!) won’t produce quality, clear thinking unless they know enough things. Knowledge begets critical thinking. Critically thinking is not immaculately conceived.

Here’s how I’ve seen this play out in my classroom. Last spring, I gave an article of the week on whatever was happening with the North Korea crisis at the time, and my students and I held a modified Conversation Challenge on the Friday of that week to discuss possible solutions to the crisis. As I was listening in on student conversations, I noted a lot of low-quality thinking — solutions were often superficial or silly, and the Fulkersonian, collaborative, evidence-based quality of conversation I was looking for wasn’t there.

Here's the thing: it was my fault. I hadn't given my students a chance to learn enough about the North Korea situation yet.

So during the subsequent three weeks, I assigned three more articles of the week relating to the North Korea crisis — if I remember right, these touched on China’s involvement with North Korea, what life is like in the prison camps, and the legacy of the Korean War of 1950-53 — and once we had read these, we held a pop-up debate to discuss the same question.

The improvement was remarkable — students built on one another’s ideas, used Paraphrase Plus, and came much closer to matching what I had originally hoped for several weeks prior. Knowledge begot critical thinking and productive, argumentative discourse. My takeaway: If we want kids to be able to intelligently analyze current issues, then we’re going to have to increase their exposure to them to a degree that probably can’t be handled by any one department.

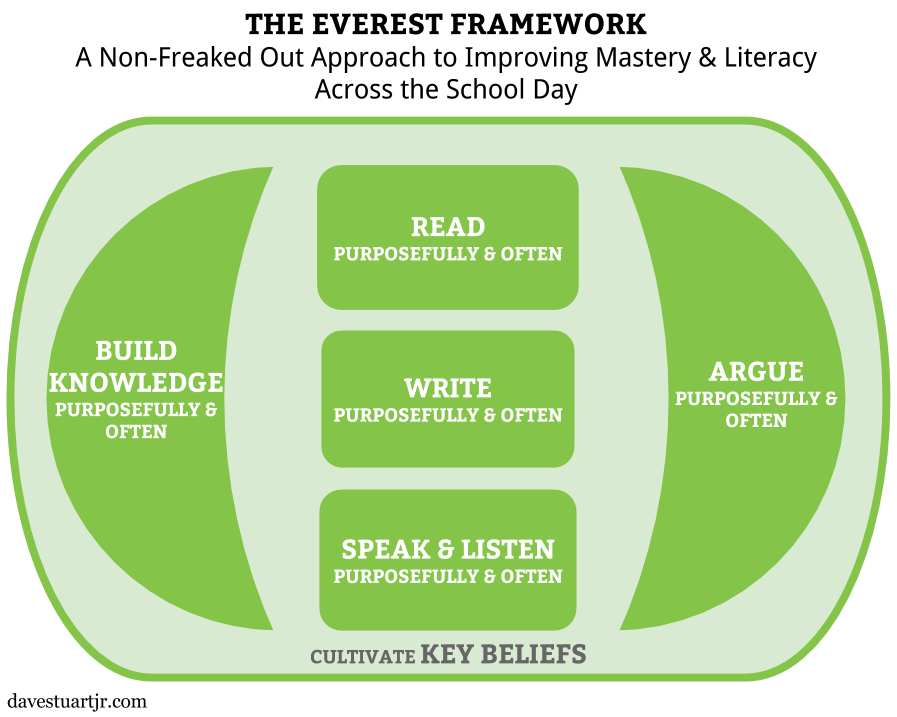

So while mastery of the material remains the #1 focus of the Everest Framework (see Figure 1), if you want your system’s high school diploma to mean, “Hey, these kids are smart about the world,” then we’ve got to figure out how current events can be better worked in 1) across the school day and 2) without using large amounts of precious time. I see two potential fruits in this area that are ripe for the picking. They are hanging so low that they are practically underground.

.

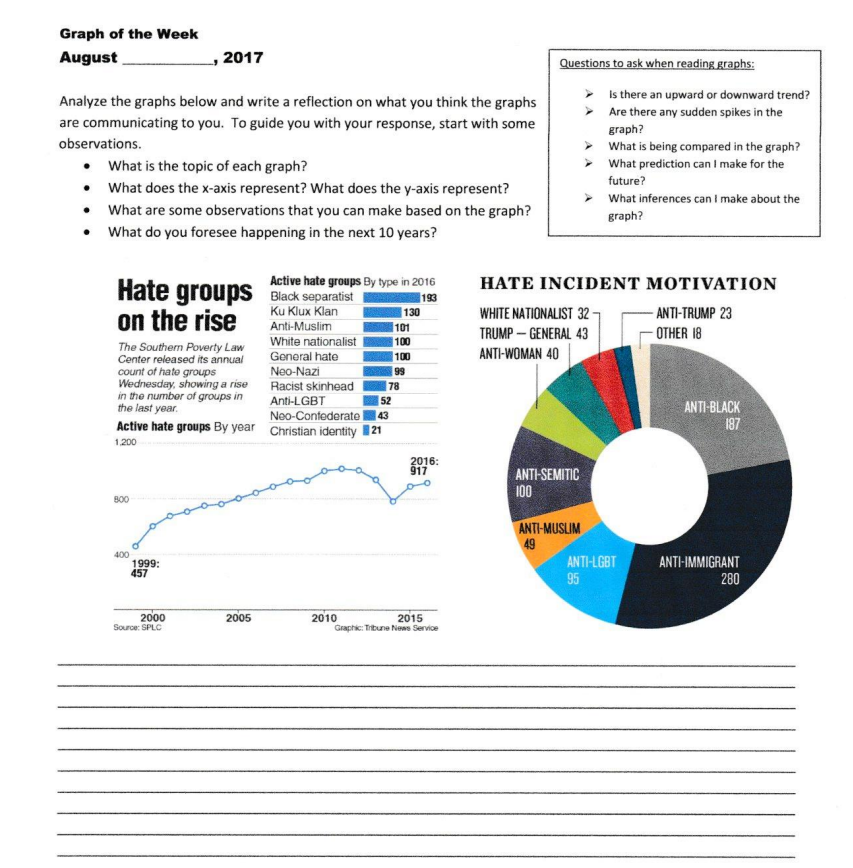

First, is it possible for math, science, or engineering classes to incorporate a current events graph, even once per month? Kelly Turner has made a ton of these, so you don’t need to create them. In Turner’s Graph of the Week, students are given prompts that guide them from comprehension (What’s the topic of each graph? What does the x-axis represent?) to analysis (What are some observations that you can make based on the graph?), and they’re required to write a half-page reflection on “what [they] think the graphs are communicating.” Turner even provides a free “Intro to the GOTW” PowerPoint for teachers to use when they roll out the GOTW assignment; I used it last spring to great effect.

Something like this need only take 15 minutes maximum of class time each week, and it can take less once students are used to it. Importantly, grading on this should not be intensive. The primary purpose of the assignment is knowledge-building, and the secondary benefits include practice with quantitative reasoning, graph reading, and writing in the content areas. (I would place this in the Readable category of the Pyramid of Writing Priorities.) On Fridays when the assignment is due, we can conduct brief Think-Pair-Shares to insure against any widespread misunderstandings. Such approaches won’t be perfect, but they’ll be marked improvements from where we currently stand. Perfectionism behind, improvementism ahead.

And mind you, the teachers we encourage to undertake this strategy need to hear, repeatedly, that we want mastery across the school day. We’re fools to devalue content mastery. Mathematical mastery is important; a mastery of the sciences is important. But if we want a more well-informed, clear-thinking populace, then we’re all going to need to chip in to create that.

Second, can our social studies, ELA, health, and/or business courses introduce a weekly, bi-weekly, or monthly current events article? These articles can be found ready-made by Googling “article of the week.” (The AoW, of course, originated with Kelly Gallagher and was first published in Readicide.) Articles can also be found on a dizzying range of topics at Newsela.com, which includes Lexile ranges for each article (translation: reading levels can be lowered to well within range for upper elementary and middle school students). Again, such article of the week efforts ought not to become a grading strain — Gallagher and I spend about 4 seconds marking each paper because we’re assigning them primarily for knowledge-building (and all grading must start with the end).

Of course, there are also secondary benefits when we systematize the inclusion of regular current events articles: our students get the opportunity to read and write more. Since quantity precedes quality, this is no small boon. Mind you, such efforts couldn’t just be chucked at students. For teaching with articles, I recommend 9 simple moves such as hooking and previewing important vocabulary words — moves gleaned directly from Mike Schmoker's Focus.

With regular articles and graphs in place, we'd next want to target things like homework completion rates. Too often, we don't try things like this because we say things like, “I'm not going to try this because only 50% of my kids will turn the work in.” Please notice that such ways of thinking devalue the 50% of students who would take advantage of an opportunity. This is something I hope my children's teachers never do, so it's something I won't do. You and I are in the business of providing opportunities, not guaranteeing results.

Like always, this is all just rough draft thinking. Thanks for reading.

Leave a Reply