Here's a multiple choice question that can really teach us something:

Learning is _____________.

A) when I take in new information.

B) about remembering, using, and ultimately understanding information.

C) difficult but important.

D) about improving as a person and widening my perspective.

E) a process that takes place every day of our lives.

F) not only studying at school but also knowing how to be considerate to others.

How would you answer that? I'll leave a few blank spaces here so you can answer it without being tempted by The Correct Answer.

Got it?

The Answer

The above options are taken from a tool created by Nola Purdie and John Hattie to measure student conceptions of learning [1]. The tool asks several dozen questions (some of which I just asked you), and those questions can be grouped into the following clusters, which I'll line up with our options above.

A) Learning as gaining information

B) Learning as remembering, using, and understanding information

C) Learning as duty

D) Learning as personal change

E) Learning as process

F) Learning as social competence

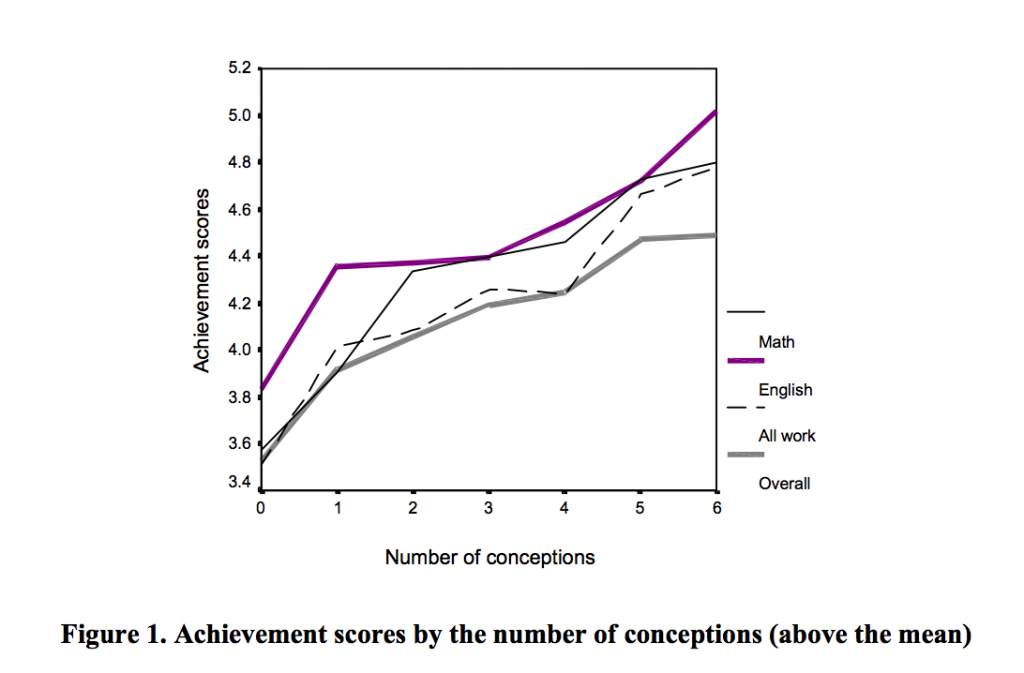

Interestingly, I find that teachers (myself included) tend to operate from (or at least communicate) just one or two of the above conceptions of learning. Which is fine, right? Until you see what Purdie and Hattie discovered when they compared the quantity of conceptions of learning a student held with that student's achievement. (See Figure 1, which is taken from Purdie and Hattie, 2002 [1].)

In other words, the “Correct Answer” to our multiple choice question is, at least when it comes to student achievement, all of the above. I don't know why that is, but my guess is that a student with such a broad array of outlooks has an easier time engaging with any learning task she's presented with.

This is fascinating because, at least in my experience, teachers tend to assume that their philosophy of learning is the right one — “Everyone knows learning is ___.” Progressive teachers are certain learning is about the process or personal change, but they generally flinch when learning is considered a duty or simply about information. On the other hand, traditionalists get frustrated when learning is presented as a fuzzy process or a personal journey; they focus on building of knowledge and the importance of this for a well-functioning democratic society.

But according to Purdie and Hattie, both the progressives and the traditionalists are only partially right — the most productive view of learning is one that encompasses all of them.

How do we help kids build a full spectrum of conceptions of learning?

I don't have any hard and fast answers here (nor do I see any in the Purdie and Hattie studies used in researching this post), but here are the hunches I'm acting on.

First, it's probably worth putting the multiple choice question at the start of this post up on the board as a warm-up, leading kids in a brief discussion of how learning can actually be any one of these things, depending on the task at hand. I would probably end by sharing with them Purdie and Hattie's Figure 1, encouraging them to open their minds to the many conceptions of learning. It wouldn't be a bad idea to have a simple, hand-written poster in the class with all of these on them.

That, by the way, would be an interventional approach to affecting the conceptions of learning in my kids — it's one-and-done, much like the Yeager & Miu study I shared a year or so ago.

It's likely that the most robust method for broadening our students' conceptions of learning is contextual rather than interventional, creating classrooms in which all of the conceptions are reinforced by learning tasks. Practically, this means using the conceptions as a filter through which to view our lessons and assignments. In X lesson or Y assignment, what conception of learning am I reinforcing? Let me examine this using two sample assignments from my classes this year.

Sample Assignment 1: Memorizing 120 dates in APWH.

I can communicate this assignment through several of the conceptions of learning. First, it is about acquiring information. But more importantly and strategically, it is about remembering, using, and understanding this information for a long time. Also, this is difficult and certainly not always fun — that's learning as duty. Yet when the work is through and kids are recognizing dates they've memorized in texts, in videos, in conversations, in movies, and as they begin to make use of an ever-accessible timeline that doesn't require wi-fi, they start seeing themselves differently and being proud of their improvement (learning as personal change). The way in which I talk about this assignment and the ways in which I lead students to approach it and to converse about it and reflect on it — these are the moves that help develop more diverse conceptions of learning in my kids.

Sample Assignment 2: Reading Things Fall Apart in general world history.

Achebe's novel isn't part of our school's mandated world history curriculum, which forces me to move quickly through the mandated units so that we have time for Things Fall Apart at the end of fall semester. I regularly tell my kids that we work harder than the mandated curriculum requires so that we can work even harder at reading a great (but challenging) novel, and I try to frame that motivationally by communicating:

- we are a group that does hard things, including working hard at learning (learning as duty);

- this hard work makes us develop as people, and reading Things Fall Apart will broaden our horizons (learning as personal change);

- Things Fall Apart will enable us to take a location-specific look at the effects of imperialism on one African society (gaining information), and this will in turn help us understand imperialism at a greater level than we would if we were not to read it;

- Things Fall Apart will also lead us to consider what it means to be masculine or feminine, and this ought to help us better relate to ourselves on a day-to-day basis (learning as process) and others (learning as social competence).

The big idea for us as teachers

The big idea for me is that I want to internalize each of these conceptions of learning — I want to memorize them and use them — so that I communicate them all throughout the year. This, I hope, will help me build more lessons and assignments that engender the full spectrum of conceptions in my kids. In light of Purdie and Hattie's research, I can no longer afford to emphasize solely the conceptions I'm naturally fond of; I need to communicate them all. [2, 3]

Footnotes:

- Purdie, N., & Hattie, J. (2002). Australian Journal of Educational & Developmental Psychology, 2, pp 17-32. I accessed it here.

- For what it's worth, in an earlier study the researchers found that students holding a learning as remembering, using, and understanding information conception “used a wider variety of learning strategies and were more likely to engage in strategy use in order to learn,” (Farrington et al, 2012) [3]. You can find that study at Purdie, N., Hattie, J., and Douglas, G. (1996.) Students' conceptions of learning and their use of self-regulated learning strategies: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 87-100. (Available here, but not for free.)

- I learned of Purdie and Hattie's study from Farrington, C.A., Roderick, M., Allensworth, E., Nagaoka, J., Keyes, T.S., Jonson, D.W., & Beechum, N.O. (2012). Teaching adolescents to become learners. The role of noncognitive factors in shaping school performance: A critical literature review. Chicago: University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research. (Accessible here.)

Thank you to Camille Farrington and her team. Their report, cited in Footnote 3 above, was the seed for this article.

Leave a Reply