Teaching is this hugely complex, challenging calling, and that's why I'm glad it's mine — I don't foresee getting to a place where I'm like, “You know what? I've got this all figured out. Done. Turn on the cruise control.”

To be honest, I think few of us will get there, and if we do, it will be after about 30 years and 100,000 hours of intensive, deliberate practice.

But we don't need to wait until we have it all figured out before we can start being dang good teachers who make a huge impact with our careers. I think that all of us, if we train ourselves to focus in, can fairly quickly become adept at the 20% of things that yield 80% of the results.

What is the 80/20 rule?

The 80/20 rule, also known as the Pareto Principle, is essentially this: for many events, roughly 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes. It's named after an economist named Vilfredo Pareto, who observed over a hundred years ago that 80% of the wealth in Italy was held by 20% of the population, and (get this) that 80% of the peas in his garden were produced by 20% of the pea plants.

Peas and people. Pareto was intrigued.

Learning guru Tim Ferriss provides some other ways of phrasing the Pareto Principle in his intriguing book, The 4-Hour Work Week:

- 80% of the outputs result from 20% of the inputs

- 80% of the consequences flow from 20% of the causes

- 80% of company profits come from 20% of the products and customers

- 80% of all stock market gains are realized by 20% of the investors and 20% of an individual portfolio

In teacherspeak, the Pareto Principle would be written like this: 80% of student achievement results flow from 20% of the work we do with students.

So what does the 80/20 rule have to do with educators?

I think we have a wretched habit in education of over-complicating the most powerful 20% of educational practices. This is a crime we all commit together: teachers, administrators, literacy coaches, authors, consultants, you name it.

At the risk of being labeled a reductionist, I've aggressively sought on this blog to boil our problems down to their roots and develop similarly boiled down solutions. Let's take a look at two examples of how Teaching the Core, thus far, has sought to bring the Pareto Principle to bear on our issues.

The 80/20 rule and the problem of Common Core implementation

The Common Core are among the best lists of literacy standards we've yet seen in the USA, but there are still far too many of them: 32 college and career readiness anchor standards, with each of those standards containing several skills of its own. In actuality, if I were to seek to develop every single one of the Common Core skills for my 9th grade ELA and history students, I'd be trying to help my students master over 100 skills.

Even if you're not in a Common Core state, the same is likely true for your own literacy standards — 100+ goals.

Forgive me for a lack of optimism here, but if the future of education in America depends on teachers being able to help students own and master 100+ literacy goals per year, I think we're in trouble. Thankfully, the 80/20 rule is likely true of the CCSS; there are a select few of those college and career readiness goals that will garner the lion's share of the long-term benefit for our kids.

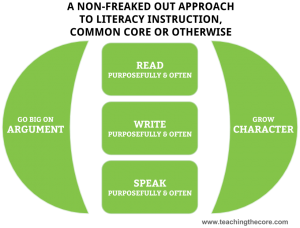

That's why I've sought to reduce them. I think the Common Core literacy standards essentially boil down to this: we need to focus on increasing the quality and quantity of reading, writing, speaking, and argumentative thinking that our students do. Why? Because these things are the core of 21st century skills.

My non-freaked out framework for literacy instruction across the content areas is a pretty mundane attempt at communicating that boil-down work, yet I think similarly simple frameworks are the only way that content area teachers especially (and even many ELA teachers) are going to internalize the importance of getting great at a few key things — in this case, we need to get awesome at helping students think argumentatively (especially in grades 6-12), and then to read, write, and speak in ways that are increasingly complex and college/career appropriate. Keep in mind, however, that I'm no fancy standards guy; I'm just a practitioner.

Notice that while the framework allows us a simple, visual device for understanding what (I think) matters most in literacy development, there's lots of work we can be doing to get better and better at facilitating and teaching toward the five elements. This framework gives us a framework for successive PD workshops (here are some of my thoughts on how to do literacy PD). I've also found that it's highly motivating for teachers — why? Because the 80/20 Rule is highly encouraging for those of us who want to work smarter, not harder.

Ultimately, this framework allows us to spend a larger percentage of our energy on the 20% of the standards that I think matter most for college and career readiness. Great schools allow their teachers to focus in on and get great at the 20% of practices that matter most. (This is essentially the central argument of Mike Schmoker's Focus.)

The 80/20 rule applied to our careers as educators

One of the key complaints I hear from teachers (and justifiably so) is that they have no time to do all the things they're supposed to do. I think this is one of the leading causes of burnout — and the Pareto Principle shows us that it's entirely unavoidable.

The liberating power of 80/20 comes from the fact that, once we start discovering what 20% or so of our practices yield the vast majority of long-term results, we can satisfice (see Number 4 of this post) the heck out of the 80% of things we do that don't matter a whole lot, such as:

- Responding to every email the second it comes in. This isn't highly impactful in the long run. Solution? Check your inbox one to two times per day. Period. If you're an administrator, encourage your staff to minimize their daily inbox checking.

- Worrying over mind-numbing paperwork. Not highly impactful in the long run. Solution? Get it done and move on.

- Creating beautiful bulletin boards. Looks nice, right? But where's the long-term impact? Solution = make your instruction awesome; your room needs to serve its purpose.

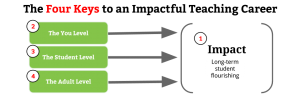

Instead of exerting energy (and anxiety and stress do exert energy, my friends) on things that don't matter, we ought instead to focus on daily improvement in three basic areas:

- Our own mindsets and attitudes

- Our work with students

- Our relationships with other adults (both teaching colleagues and others)

In pictorial form:

The point here isn't that I've created something original — it's that I've sought to boil our work down into its most potent core focus areas.

Getting “initiatived” to death in your school?

Share this post with the powers that be. Literally take the link to this post, paste it into an email, and send it to them with a brief explanation of why you think it's relevant to your school setting. I'm not writing anything ground-breaking here — Pareto's been dead for a century — but I do hope to serve as a reminder

We must be judicious about running the things we ask teachers (and students!) to do through the 80/20 filter. I've provided two examples in this post of how this can look when applied to some of our questions as educators in the USA, but there are so many more questions that need to be 80/20ed — feel free to share them, and any other thoughts you might have, below in comments.

Lisa says

I need to locate the exact source this came from originally, but I learned at a National Writing Project Invitational that only 20% of student writing needs to be graded with the proverbial “fine-tooth comb.” If we wait to assign more writing until after we finish grading each assignment, students will never get the writing practice they need or build writing stamina. This was liberating information for me as a writing instructor.

davestuartjr says

Lisa, I’d love to hear more about that source — sounds like something I need to read. Liberating indeed!

Dan says

Could it have been Collin’s Writing? Sounds similar….

Karla says

Please, share the source if you have it, Lisa! I have been telling the teachers in my English Dept that they do not have to grade so finely every piece of work.

Janice says

I responded to the survey prior to reading this blog post. The frustrations that I discuss are addressed so well in the information you shared. The 80/20 rule is going to save my mind and free my energy for more effective teaching. Thank you!!!!

davestuartjr says

Janice, I’m thrilled to hear that. Thank you for completing the survey; it’s already given me so much insight into how I can better serve folks here at Teaching the Core. Thank you!

Laura Scott says

Kelly Gallagher is the one who has said that students need to write far more than we can grade. I do like his approach of really going over work that is in it’s draft stage so by the time it gets to the turned in piece we don’t have to go over it so well.

Steve Haag says

Thanks, Dave!

Also check out Mike Schmoker’s “Write More – Grade Less”:

http://www.mikeschmoker.com/write-more.html

Susan says

Dave, non-freaked out as always… Thank you.

PHILIP BROWN says

Excellent article! The 80/20 rule is something I’m using to explore effective teaching practices as well. I am linking to your article.