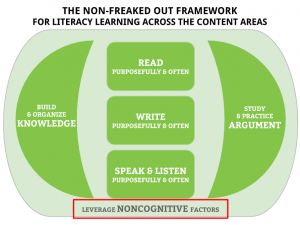

In the coming weeks, I'll be sharing the results of a “Research Sprint” that I conducted in August 2016. I wrote a fairly detailed account of the sprint in my last post, but the gist is that I read three books and 15 references within those books for a single element of the Non-Freaked Out Framework for Literacy Instruction Across the Content Areas (see Figure 1).

The element I chose is “Leverage Noncognitive Factors” — which at the time was “Study and Practice Success.” (The research sprint actually kind of mutated the NFO Framework; you can read about those mutations here.) The problem with the phrase “Leverage Noncognitive Factors” is that it sounds super boring. Also, it's pretty misleading; some of the “noncognitive” factors are intensely cognitive. But, as you'll learn in the weeks to come, noncognitive factors is just the best term for what we're talking about, better than “all the things not tested” or “character strengths” or “success skills,” because we're not talking about all the things not tested and these aren't all strengths or skills. Noncognitive factors are a cornucopia of beliefs, attitudes and behaviors, and they do affect measures of cognitive ability but they also affect measures of other things (like grade point averages).

But let's get rid of languagey stuff and just talk about something every single one of us grapples with every single day, something thickly threaded throughout the noncognitive factors: student motivation.

Whose job is student motivation?

I wrote about “triple responsibility” a few weeks ago, but don't go to that article right now. Just, from your gut, answer this: Whose job is it to motivate students?

A) It's the student's job.

B) It's the teacher's job.

C) It's the parent's or guardian's job.

D) It's all of their jobs.

E) It doesn't matter whose job it is.

In some cases, it certainly does matter whose job student motivation is. I'm thinking of the teacher who places 100% of the responsibility for student outcomes on themselves, or the teacher who places none of the responsibility on themselves. Such pathologies require an awareness of how intricate motivation is — how it depends not on a single source or factor, but upon many. D), then, is quite right because students, parents, and teachers all play a role in creating conditions that either lends themselves to or inhibit motivation.

But also, the question doesn't matter as much as a bigger one — motivating them toward what?

Motivating them toward what?

If we want them to be motivated just so they'll do our work and pass our class or get our diploma, then I find studying student motivation to be pretty boring. All of these things are important — I want my students (and my children) to, at the very least, do their work and pass their classes and graduate from high school — but they aren't ultimate.

I believe that ultimately, schools exist to promote the long-term flourishing of their students; this is our one shared, enduring standard. I may be teaching world history to ninth graders and you may be teaching Spanish to eighth graders, or PhysEd to sixth graders, or AP Physics to seniors, but what you and I have in common is our ultimate aim: the long-term flourishing of our kids. It's important that we differ in our tacks toward getting there — I'd submit that a kid can learn different and valuable things in your class that she won't learn in mine, and vice versa — but that we have clarity about what we're ultimately aiming for.

Teaching toward long-term flourishing is different from, say, teaching toward college. I do teach toward career- and college-readiness (CCR) on a daily basis — in fact, the NFO Framework was born during my study of the most widespread CCR standards, the Common Core — but these things are steps on the journey to long-term flourishing. Such readiness is not the sole point of secondary schooling, even though they are a precious indicator of whether or not our secondary schooling is doing what it should.

Once I'm clear on the Everest my class aims for — and how that Everest is the same one as your class, no matter where or what you teach — then I'm intensely interested in what motivates students to work harder in some classes than others and what I can do to factor into the equations that separate the academic Haves from the academic Have Nots.

Leave a Reply