Again and again in my professional reading, I come across thoughts that point to the possibility that the physical classroom environments we create for our students aren't as important as we might think they are.

Yet at the same time, it seems like I frequently come across some blog post or image about the physical classroom environment, and these things suggest that I'm wise or savvy or better if I spend a good deal of my time making the space fabulous.

So, I looked into it. How important is the physical classroom environment?

Environment Does Matter…

My top takeaway from Paul Tough's recent Helping Children Succeed (note: all linked-to books are affiliate links) is that noncognitive factors (see Figure 1) are most accurately and usefully conceived of not as “skills to be taught” but as “products of a child's environment.”

From Paul Tough's Helping Children Succeed:

“There is certainly strong evidence that this is true in early childhood; we have in recent years learned a great deal about the effects that adverse environments have on children's early development. And there is growing evidence that even in middle and high school, children's noncognitive capacities are primarily a reflection of the environments in which they are embedded, including, centrally, their school environment.” (p. 12)

This is corroborated by another book I read recently, a treatment of something called Identity-Based Motivation.

From Daphna Oyserman's Pathways To Success Through Identity-based Motivation:

“…[P]eople are highly sensitive to their immediate environment, automatically picking up cues about what content and what way of thinking is relevant in the moment (Bargh, 2014; Bargh & Gerguson, 2000). In this way, contexts influence what is on people's minds. People pay attention to what is on their minds in forming judgments of how frequent, likely, or typical events are” (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973).

So what we want our classrooms and schools to do isn't to look pretty (just as many of the prettiest classrooms aren't made that way primarily with prettiness in mind) as much as create places where students are thinking about their ideal future selves.

…but the Type of Environment that Matters is Largely Not Physical

Here's the rub with the importance of environment and the concept of the pretty classroom, according to Tough's reporting.

From Paul Tough's Helping Children Succeed:

“The environmental factors that matter most have less to do with the buildings [children] live in than with the relationships they experience — the way the adults in their lives interact with them.” (p. 17)

Camille Farrington and her research group — remember, they authored that critical literature review on noncognitive factors — come to a similar conclusion.

From the Farrington et al.'s Teaching Adolescents to Become Learners:

“While some students are more likely to persist in tasks or exhibit self-discipline than others, all students are more likely to demonstrate perseverance if the school or classroom context helps them develop positive mindsets and effective learning strategies.”

Context, it turns out, is more about psycho-social factors and the structures we have in place around learning. As such, one could envision all kinds of physical classroom environments as being home to the kinds of psycho-social environments that encourage positive mindsets and learning strategies. If this is the case, it stands to reason that the gorgeous classroom would be the goal of someone who has achieved preeminence in the basics of their craft (classroom management; the creation of solid lessons and units that build knowledge, facilitate motivation, and develop literacy) — or, of course, someone who enjoys interior design avocationally. (This would be a great example of one's hobby intersecting with one's work as a teacher.)

Can an aesthetically appealing setting ever have a negative impact on students?

This is a little bit of a scandalous question, but I did actually happen across one mention of this in my summer reading. According to Daniel Coyle, a comfortable, cozy, aesthetically pleasing physical space could actually have a demotivating effect on skill developers.

From The Little Book of Talent, by Daniel Coyle:

“Luxury is a motivational narcotic: It signals our unconscious minds to give less effort. It whispers, Relax, you've made it.“

To be fair, Coyle's writing focuses on the years he's spent visiting and learning from “talent hotbeds” — places that produce an abnormal amount of excellence in their students — be they tennis players, musicians, or high schoolers.

Coyle says,

“The talent hotbeds are not luxurious. In fact, they are so much the opposite that they are sometimes called chicken-wire Harvards. Top music camps… consist mainly of rundown cabins. The North Baltimore Aquatic Club, which produced Michael Phelps and four other Olympic medalists, could pass for an underfunded YMCA. The world's highest-performing schools — those in Finland and South Korea, which perennially score at the top of the PISA rankings — feature austere classrooms that look as if they haven't changed since the 1950s.” [1]

Coyle concludes that “simple, humble spaces focus attention on the deep-practice task at hand: reaching and repeating and struggling. When given a choice between luxurious and spartan, choose spartan. Your unconscious mind will thank you.”

Which is pretty bold, right? “When given a choice between luxurious and spartan, choose spartan.” As a guy who teaches in what I would call a pretty nice classroom — books lining shelves on a wall, a big painting of the world in the back — this gives me pause.

My recommendations for classroom builders around the world

So what does this all lead me to conclude about whether our classrooms need to be pretty? A few things:

- Outcomes are more important than means. Just as teachers ought to pride themselves not on the hours they put in but rather on the results they produce, so too it goes with physical classroom spaces. The long-term flourishing — not the hours I spend preparing for it — is the point. (I used to get this completely backward, glorifying myself for long hours on the job and looking down on any teacher who left before 5pm. This makes no sense.)

- Beliefs are more aligned with long-term flourishing than feelings. We want our classroom contexts — of which the physical space is a very small part — to build a durable set of four academic beliefs. Ideally, these beliefs would last longer than when the kids are with us (and the good news, as we've learned in this article, is that the beliefs don't seem to be caused as much by the classroom space as by the context — relationships, structures, curriculum). Going directly from Daphna Oyserman's identity-based motivation strategies, we can aim to have the physical space “make the future seem relevant to the present” and make “strategies feel ‘identity-congruent'” (i.e., the kinds of things people like me would do).

- Peace and stability are more important than cushions and wall paint. From Paul Tough's Helping Children Succeed (pp. 15-16, 17):

“On a cognitive level, growing up in a chaotic and unstable environment — and experiencing the chronic elevated stress that such an environment produces — disrupts the development of a set of schools, controlled by the prefrontal cortex, known as executive functions… which include working memory, self-regulation, and cognitive flexibility, [and] are the developmental building blocks — the neurological infrastructure — underpinning noncognitive abilities like resilience and perseverance. They are exceptionally helpful in navigating unfamiliar situations and processing new information, which is exactly what we ask children to do at school every day…. The environmental factors that matter most have less to do with the buildings they live in than with the relationships they experience — the way the adults in their lives interact with them, especially in times of stress.”

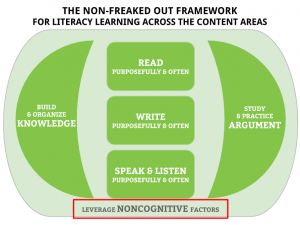

- Building a curriculum that centers on a large quantity of quality reading, writing, speaking, arguing, and knowledge-building opportunities for kids is more important than building a dream classroom. The NFO Framework helps me keep that in mind.

But finally, assuming all these things are in place or you're an internal designer at heart, go to town building a pleasant physical classroom environment. Have at it!

Footnote:

- South Korean students are notoriously unhappy, but Finnish kids are reportedly quite happy, suggesting that non-physical aspects of a student's environment are what predict things like happiness and achievement. For more on this, see Amanda Ripley's The Smartest Kids in the World.

Annette Reynolds says

Loved this article. It’s always nice to read something that affirms what I try to do in the classroom. I have always felt that the relationships we build in the classroom are the critical component.

davestuartjr says

I’m with you, Annette!

Brooke M says

Thank you for this article. It’s an interesting take. I vaguely remember you writing before about a few words or phrases that you do post around your classroom though. Can you direct me to that post or share them?

davestuartjr says

Brooke, maybe it was my “Do Hard Things” article? I have Do Hard Things, Never Finished, and Details Matter posted at the front of my room. Maybe you have seen them in pictures or something?