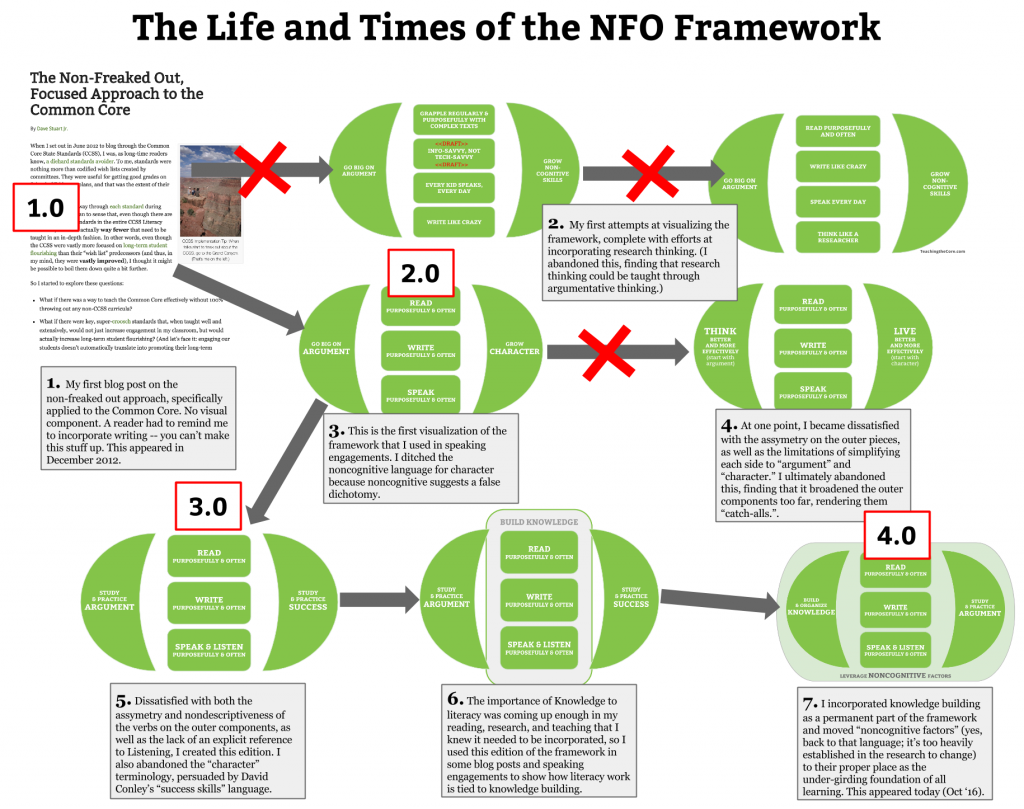

I've been writing about and teaching from the Non-Freaked Out (NFO) Framework for years now, and as a result it's gone through several iterations, some that have stuck and some that haven't (see Figure 1). James Clear writes that “it's not the work, it's the re-work.” I have certainly found that to be true with this idea, which is both thoroughly unoriginal and eminently useful to me as a teacher, a thinker, and a speaker.

The goal of the framework has always been to encapsulate the most important things I need to do as a teacher and to make that encapsulation survive the trip across the hallway into other classrooms and content areas. Given the stressful nature of teaching (see my last post for ample proof of that), any such encapsulation would need to be simple enough to hold in your head with minimal study, having it ever handy when faced with the thousands of decisions you make in a day. Yet given the important nature of teaching, the framework also needed to be robust enough to use as a guide for professional development for a long, long time. Simple enough to explain to a child, deep enough to explore for a career: that is the goal.

Recently, I came to a breakthrough that I feel is important, a breakthrough I would not have had if I had allowed the winds of policy or urgency to completely hijack my professional journey. There is plenty I have had to dodge, look past, ignore, or satisfice to stick with this idea.

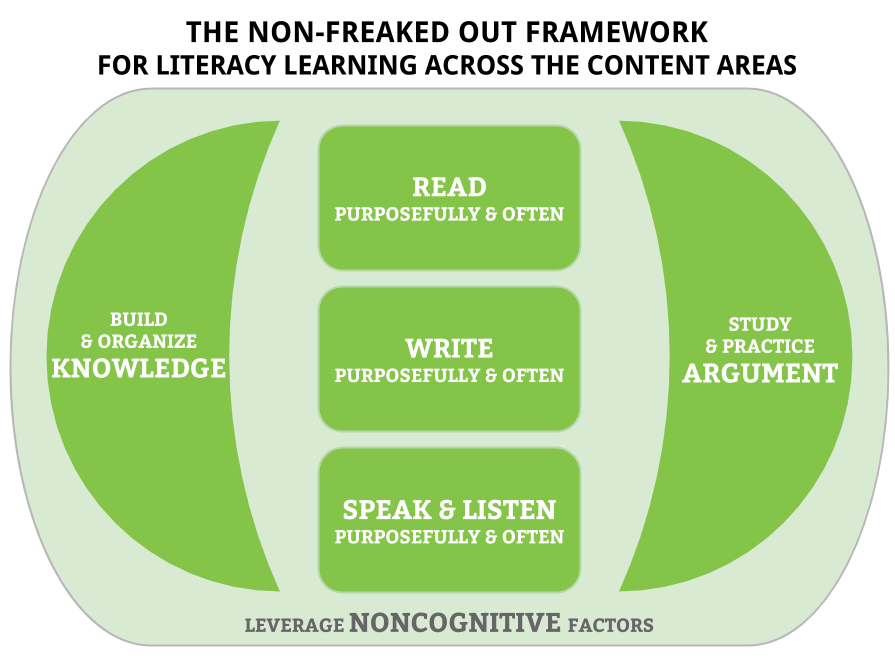

Here is Version 4.0 of the NFO Framework.

An explanation of the two important changes

On “noncognitive factors”

It has always been awkward having noncognitive skills (or character strengths) on the righthand side of the framework. When I speak or lead workshops on this topic, I work through it right to left, and as a result the noncognitive skills or character strengths feel like an afterthought, like they're getting tagged on at the end.

Which is really crazy because for every teacher in the world things like student motivation, student work ethic, and student long-term success are definitely not afterthoughts. Rather, these things undergird everything else we do. They are the foundation upon which learning rests, and they provide points of great leverage. A subpar teacher can achieve incredible results if all of his students are motivated.

And because they're not exactly all skills, I've taken to the term noncognitive factors, borrowing directly from the logic of Camille Farrington and her colleagues in their insanely useful critical review of over 400 pieces of the research literature on this topic, which you can freely read here, I mentioned in this recent post, and will be writing more about in the weeks to come. Really, when we talk about these things that aren't tested, these things that most predict l0ng-term flourishing outcomes, these things like the ways kids think about school, the degree to which kids are motivated, whether or not kids actually do the work, whether or not we as their teacher have credibility, we're talking about a set of factors. And, since the research literature for over a decade has been labeling these things as “noncognitive,” Farrington and her colleagues just refer to them as that. The label suggests a false dichotomy, but it's a firmly rooted label, one that is unlikely to change. So that's why you see noncognitive factors in Figure 2.

On “knowledge”

I've written before about how knowing things is inseparable from literacy, and Kelly Gallagher has described how he created the article of the week assignment primarily to help kids know more about the world. Despite these things, I've kept knowledge building separate from the NFO Framework, paying lip service to it in a similar fashion that the ELA Common Core document does in its introductory bits. “Yes, it's important to develop rich content knowledge, but let's move on now to reading or debating.”

You really can't move on like that if your goal is the highest quality student work. There's a ceiling on the quality of reading or writing or speaking or arguing we can expect when we forsake deep, robust knowledge-building, especially in the content areas. Sure, everything's available through Google now, but it's a pretty clunky literacy when you're constantly asking your device “What's this?” For my own children, I want Google to be a tool towards the ultimate end of them knowing a lot of things. The brain is beautiful and untapped; shame on us if we don't seek to help our students put as much data into it as possible. The most impressive artificial intelligence breakthroughs of the last ten years have come as a result of machines gaining access to lots of information; they get smarter through knowing more, not less.

So there's that. I think it's finally time to write my next book.

Erica Lee Beaton says

Cheers to clarity, revision, and that next book!

davestuartjr says

Thank you my friend