“The most routine abstract thought very often struck him with an uncommon force and would stir him up remarkably. . . . A simple idea, sometimes very familiar and commonplace, would suddenly set him aflame and reveal itself to him in all its significance. He, so to speak, felt thought with unusual liveliness.” — from Joseph Frank's Dostoevsky, p. xiv

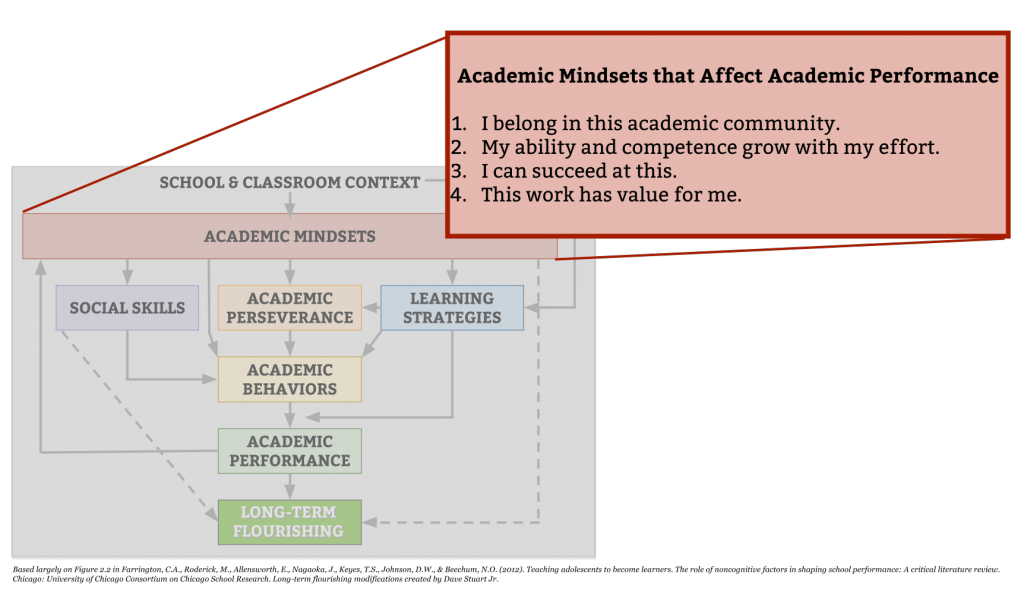

Last time, we looked at Camille Farrington's four mindset statements (see Figure 1), examining their utility as an analytical tool for both conceptualizing and troubleshooting noncognitive student struggles (for example, struggles with motivation). This time, let's discuss these from a philosophical points of view and then drill down into matters of strategy.

And please, as we go through this, remember that you and I are not omnipotent. Our job isn't to guarantee that every student develops these mindsets any more than it is a doctor's job to guarantee that a patient lives. That isn't our job because it can't be our job. Rather, we do what we can to promote the long-term flourishing of our kids. Keeping that firmly in mind, let's continue exploring the four academic mindsets as a helpful, 80/20-style means toward understanding and leveraging noncognitive factors.

Belief “works” when it becomes felt or operational

As tempting as it is to think we can just tell kids about these mindsets, tell them that these are the things they need to believe, that won't get them very far. Certainly, such an approach isn't completely useless — we are, after all, communicating truth. It's true that believing these things forms the kind of attitude and disposition that makes learning easier and more rewarding.

The trouble, though, is that we need kids to do more than intellectually assent to the mindset statements — “Yes, fine, I can succeed in here.” I'll never forget when, upon reading Dweck's Mindset, I began telling my kids about growth mindset and using the right kind of praise. Then I had them take Dweck's mindset test, and I was pleased to find that virtually all of them were given good news: they had growth mindset.

Except the problem was the mindset test results didn't match many of the behaviors I saw or explanations for poor performance that I heard: “I'm just not a reader.” “Homework is pointless.” “I'm not going to get better at public speaking no matter how often we do it.”

The issue was that, while my kids were agreeable to the fact of growth mindset, it wasn't a living truth for them. It was intellectual, not operational.

Or, as one of Fyodor Dosteoevsky's biographers puts it in this article's epigraph (dude, I put an epigraph on a blog post — so elegant), the truth wasn't felt.

Our goal, then, is to have our students not just know about the four academic mindsets, but to feel them, to live and act from them, to have them be a part of who our kids are.

So how do we do that?

The two means for creating belief: interventions and contexts

Thankfully, the literature doesn't leave us high and dry here, instead suggesting two clear means through which to make the mindsets functional truths in our kids' lives.

Interventional approaches

First, there are interventional approaches — things like Yeager and Miu's one simple lesson that mitigated the onset of ninth grade depression, or Chris Hulleman's expectancy-value tasks, or Dweck's study where some kids are praised for hard work and others are praised for being smart, or that “thought of the day” pep talk streak you've been doing with your students.

Benefits of interventional approaches: quick, short-term, relatively little sustained effort required to implement them, no systemic changes needed

Drawbacks of interventional approaches: many interventions to choose from; many interventions target specific groups (e.g., low performers; African American males; females in math classes; etc); some evidence suggests interventions may be most impactful in experimental situations (versus situations where they are in widespread use) [1]

Contextual approaches

Second, there are contextual approaches that aim to create “everyday educational experiences [that] lead students to conclude that they belong in school, that they can succeed in their academic work, that their performance will improve with effort, and that their academic work has value” (Farrington, p. 36). Farrington and her colleagues cite a report by the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine that “summarized decades of research to identify school conditions that promote… positive academic mindsets,” including:

- “challenging but achievable” student learning tasks;

- “communicating high expectations for student learning and providing supports that allow students to meet these expectations”;

- “making evaluation practices clear and fair and providing ample feedback“;

- “reinforcing and modeling a commitment to education and being explicit about the value of education to the quality of one's life“;

- “providing students with opportunities to exercise autonomy and choice in their academic work”;

- “higher-order thinking” tasks;

- “structuring tasks to emphasize active participation in learning activities” (versus passively receiving info);

- “requiring students to collaborate and interact with one another when learning new material” (e.g., through think-pair-share, the conversation challenge, or pop-up discussions and debates);

- “emphasizing the connection of schoolwork to students' lives and interests and to life outside of school.” [2]

Benefits of contextual approaches: mindsets are more likely to stick and to transfer, being developed over time versus in a single intervention.

Drawbacks of contextual approaches: more laborious, more of a process; requires that teachers and principals understand the research on academic mindsets and the mechanisms by which classroom variables affect student beliefs

In short

The wisest approach to instilling belief in our kids — in the power of schooling, in the magic of learning, and the great, unknowable potential that lies within each of them — leverages both short-term interventional and long-term contextual efforts.

Footnotes:

- These caveats are discussed at length in Farrington et al's Teaching Adolescents to Become Learners, which is freely available here (pp. 35-36).

- Taken from Farrington et al, p. 36.

Wendy says

Dave –

Years ago when my state DOE mandated that we teach character ed (and that was about the extent of the guidance), I worked with a wise gentleman who presented character education lessons that he created to our staff. What I remember him saying, and I have come back to this ‘mantra’ time and time again when trying to make sense of everything in education from resistance to change to promoting a growth mindset, is this: “You have to know the good before you can do the good or be the good. Know the good, do the good, be the good.”

To often we deliver information or ideas and expect change immediately. Thinking of learning (especially around your academic mindsets) through that framework – first you have to know (and understand) what it means, then you have to consciously work at it, then it is just who you are. Whether it’s resilient, hard-working, honest, fair, high-achieving, or any number of other things…it takes practice and conscious effort to become ‘that’.

Thoughts?

davestuartjr says

I’m blown away, Wendy — those are my thoughts. Know, Do, Be — this is exactly what I’ve been working on this year with these mindsets with my kids. That is the process. That gentleman was right, and you are generous and wise to draw the connection and share.

Wendy says

I love your blog and the work you do and admire you tremendously for your work as an educator!

The challenge is to keep moving on the continuum…too often we talk a good talk and stop there; our actions tell a different story.