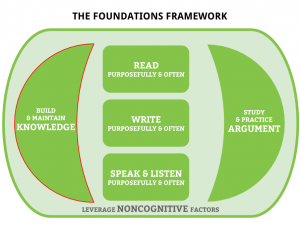

At the time of this writing, I have a clear idea of how you and I can improve our practice in five of the six components of the “Non-Freaked Out” Foundations Framework for Literacy Instruction Across the Content Areas.

For argument, reading, writing, and speaking/listening, a general pattern emerges: quantity precedes quality. From this, we have an obvious strategy: increase the amount of reading, writing, speaking, listening, and arguing that our students do, and then use efficient means for improving the quality of the reading, writing, and so on, that our students are capable of.

For noncognitive factors, I see three logical and robust areas of work. The literature lines suggests that three areas are largely within our control and likely to amplify the work we do in the classroom: our students' academic beliefs, our students' use of learning strategies, and our students' perception of our “teacher credibility.”

This leaves us with only one area in which I'm still roughing out ideas, at least at the time of this writing [1]: Build and Organize Knowledge. In prior versions of the Framework (you can see them all here), there wasn't a Knowledge piece at all. But the more I taught with the Framework in view, the more I led workshops on it, the more I researched its components, the more I came to see that knowledge is non-negotiable. For example, it affects how well we read and how well we argue.

So, while I don't have the exact “Next Steps” for knowledge-building like I do for the other parts of the Framework, I do have one thing to share: knowledge builds on knowledge. This insight, impressed upon me in reading E. D. Hirsch, Jr. and Daniel Willingham especially, is one of those “hiding right in front of us” things. In a profession that wants to jump straight into the highest order thinking, we struggle with the notion that there needs to be a robust knowledge base before the highest order thoughts can come.

Consider a simple example: whenever I write a blog post, it's common for me to wonder at the exact meaning of a word. So I open a new tab, do a Google “define” search, and quickly ascertain whether the word I had in mind matches the nuances of the definition that my search pulled up. Had I not known the word I was searching for to begin with, I wouldn't have been able to look it up, and even if I had, I wouldn't have been able to learn the added nuances that my quick search garnered. Knowing the word enabled me to know more about the word. Without the knowledge, I wouldn't have gained the knowledge.

And I see this in world history all the time, of course. If a student doesn't know where Anatolia is, she won't gain as much knowledge from reading a selection on the Hittites as a student who can locate Anatolia. Or when teaching mechanics in English class (there's an amazing set of books for that), the rules for comma usage don't help all that much if you don't know what makes a sentence. You need to know subjects and verbs before you can do anything more with a comma than “placing one where there's a pause.”

With any of the components of the Framework, we have to know why it matters, why it merits our tunnel-visioned study and practice, if we're going to sustain the long-term work it takes to develop expertise. So, while I don't have the nitty gritty determined for Build and Organize Knowledge, here's another piece of the “why”: knowledge begets knowledge.

Footnote:

- At present, I'm at work on a book about the Foundations Framework, and so I've written several months of blog posts (including this one) well in advance to give me time to focus on writing the book. If you'd like to be kept in the loop on the book's progress, please join this list here.

Cynthia Withers says

This blog post has given me a lot to think on. I especially like the knowledge part. I guess that is something I do – I look at each standard and pull out the skills (knowledge) that are needed to be successful in mastering it. Many are just basic skills students should have. Bad assumption. So I always do a quick review on the skills to be sure they are fresh in the students’ minds. Doesn’t always work, but I feel they have exposed to them and the more exposure they get, the better they will be. I am a middle school teacher, 6th grade language arts and social studies. At the beginning of each school year, I am always amazed at the lack of skills my students bring from elementary. As I am a teacher and not a re-teacher, a quick review of the necessary skills is in order.

Jennifer Lenon says

The foundations of your framework remind me of the work done by Hattie, Fisher and Frey related to surface, deep, and transfer learning. It has been very helpful to me and to the teachers that I work with. A great article on this is in the Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, Vol 60, No. 5, called “Surface, Deep, and Transfer? Considering the Role of Content Literacy Strategies.”

davestuartjr says

I need to get ahold of this article, Jennifer — thank you for the heads up!

John Zeck says

I just read October 2016 | Volume 74 | Number 2 Powerful Lesson Planning Pages 46-50

Issue Table of Contents | Read Article Abstract; Pursuing the Depths of Knowledge

Nancy Boyles where she also references Webb’s Depth of Knowledge to help us teachers and coaches come to a deeper understanding of how to insure rigor in our lessons.