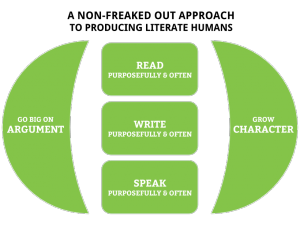

The point of the Non-Freaked Out Approach to Producing Literate Humans (still working on that title; see Figure 1) is to make it easy for teachers to remember what we ought to become very, very good at. It helps us ask at the end of a hard day, “Did I help my students grow in one of these areas today? Okay, then I did my job.” And it's a way of organizing our own professional development; we can ask at the outset of each school year, “How do I intend to push myself and my students to grow in these five areas this year? What can I learn about these things to grow in the most critical areas of my craft?”

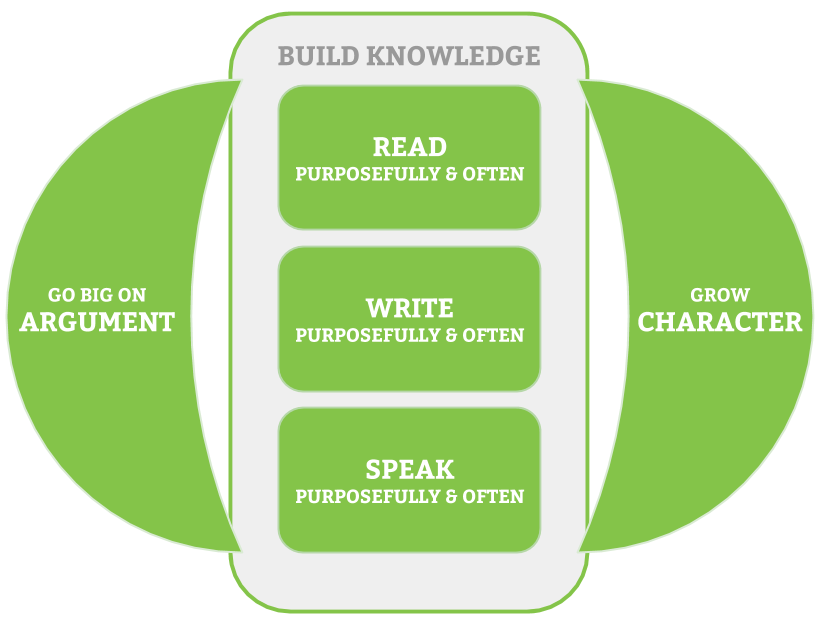

But one weakness of the NFO Framework is that it makes a pretty dangerous assumption: that you're teaching a knowledge-rich curriculum and helping your students build knowledge as you teach them to argue, read, write, speak, and develop character. In “There's No Such Thing as a Reading Test,” E.D. Hirsch, Jr. and Robert Pondiscio explain how knowledge is inseparable from reading ability [1]. Unless we have background knowledge about what we're reading, we won't be able to read it at all — we'll simply decode weird words [2]. If you don't have knowledge, you're not going to make meaning.

Hirsch and Pondiscio illustrate the concept well:

Cognitive scientists describe comprehension as domain specific. If a baseball fan reads “A-Rod hit into a 6-4-3 double play to end the game,” he needs not another word to understand that the New York Yankees lost when Alex Rodriguez came up to bat with a man on first base and one out and then hit a groundball to the shortstop, who threw to the second baseman, who relayed to first in time to catch Rodriguez for the final out. If you've never heard of A-Rod or a 6-4-3 double play and cannot reconstruct the game situation, you are not a poor reader. You merely lack the domain-specific knowledge of baseball to fill in the gaps.

This simple fact — that knowing stuff is inseparable from being able to read stuff — is why great teaching will always be concerned with both skills and content. Sadly, since the majority of educators who implemented the Common Core State Standards did not read and reflect upon their introductory matter, it became popular (and fallacious) to declare that content isn't what counts — skills are. In the CCSS era, there are no distinctions between science and social studies and English teachers anymore; we're all reading teachers, right? And thus was won a great victory by champions of literacy everywhere!

But it's not true; you can't be literate without knowing stuff, and the Googleability of seemingly everything doesn't change that. Yes, disciplinary teachers must teach their students to read purposefully (Figure 1, top center) within their discipline, and I think it's critical that kids are reading often across the disciplines as well. But as we're doing this purposeful and frequent reading work (and writing work, and speaking and listening work) in our courses, one of the primary purposes for which we're doing these things is to help our students to build knowledge. (See Figure 2.)

A big part of a teacher's job is helping kids learn new stuff. It's popular to mock the image of a teacher funneling information into an empty student brain, but don't settle for a seat with the mockers [3]. The “Guide on the Side” versus “Sage on the Stage” dichotomy is false; it dangerously oversimplifies the complex truth that the best teachers serve as both sage and guide, possessing the wisdom to decide when to work from either place.

If I have more food than I know what to do with and I meet a man who will soon run out, am I to only guide the man toward finding new food of his own? Of course not. I ought to strengthen him with the extra food I have while also teaching him to produce his own. Sage and Guide, Stage and Side.

You, teacher, have an amount of knowledge in your brain (and hopefully in your curriculum) that exceeds the amount of knowledge in the brains (and prior curricula) of your students. When our kids graduate our high schools, I think it's only right that they have thousands of bits of data in their heads that they wouldn't have had were it not for us. Brains filled with information can do things that brains empty of it can't, Google or no Google.

It is true that the work of entering data into the brain isn't primarily the teacher's role, and it's also true that our students don't come to us devoid of knowledge. Yet the teacher should have a knowledge advantage over her students, and it seems right and just that we would want to diminish that data advantage by the time our students leave us. (When that data advantage doesn't exist, rectifying the situation ought to be of primary importance to the teacher.)

I'll conclude with a proud and thankful Dad story. This week, Hadassah (our oldest) completed kindergarten, and I'm so thankful that Mrs. Ellsworth, her phenomenal teacher, taught her how to read this year. What a profound gift to give a child: the ability to pick up a book and decode its words.

Yet I'm equally thankful that Mrs. Ellsworth taught Haddie and her classmates about animals. My sweet daughter knows things about camels and giraffes and donkeys that surprise her dad. And because of that animal knowledge, any reading that Haddie does this summer about animals is going to be better and richer reading. She won't simply decode the words in books on giraffes or monkeys or dolphins, she'll comprehend them. She'll build knowledge through reading, which will in turn make her better able to build more knowledge through reading, and all the while she'll be becoming a much stronger reader.

Skill and knowledge are inseparable.

Footnotes:

- Article freely available at The Prospect. Thank you to Kelly Gallagher for sharing this article with me during our interview this past winter. You can access that interview here.

- Kelly Gallagher famously created the Article of the Week assignment after a student asked “Who's this Al guy?” after reading an article on Al Qaeda.

- The Hebrew Psalter begins with a warning: “Blessed is the man who walks not in the counsel of the wicked, nor stands in the way of sinners, nor sits in the seat of scoffers.” (Psalm 1:1)

[hr]Thank you to Mrs. Tessa Ellsworth, an inspiring educator who blessed my daughter this year. Thank you also to Mr. E.D. Hirsch, Jr. and Mr. Robert Pondiscio for their great article, and to Mr. Kelly Gallagher for sharing the article with me to begin with.

andrea dye says

Hi Dave! I’m so glad I came across this blog today. The issue came up at my school site when I shared a SBAC content specific vocabulary list across departments. One of the teachers was a little dismayed by the subtle suggestion that all teachers teach literacy. This blog offers some clear support for both sides of the argument. I feel much better “armed” to have this conversation and better informed. Thanks!