Here's a counterintuitive idea in our present age of toxic disagreement: the best school cultures are riddled with arguments.

To be clear: culture-enriching arguments aren't the same things as the radioactive Twitter ranting, name-calling, outrage-mongering, or Facebook flame-warring that we're exposed to these days. No. Those kinds of things kill culture; like cesspools, they breed division and unhappiness, muddying our thoughts and disabling our minds.

I'm talking about argument here. Listen to the way that leading thinkers describe argument:

- “…argument literacy, the ability to listen, summarize, and respond, is rightly viewed as central to being educated” (Gerald Graff in Clueless in Academe: How Schooling Obscures the Life of the Mind)*

- “The goal [of argument] is not victory but a good decision, one in which all arguers are at risk of needing to alter their views, one in which a participant takes seriously and fairly the views different from his or her own” (Richard Fulkerson in Teaching the Argument in Writing)

- “And that's all argument is–not wrangling, but a serious and focused conversation among people who are intensely interested in getting to the bottom of things cooperatively” (Joseph Williams and Lawrence McEnerney in “Writing in College, Part 1”)

- “To disagree well you must first understand well. You have to read deeply, listen carefully, watch closely. You need to grant your adversary moral respect; give him the intellectual benefit of the doubt; have sympathy for his motives and participate emphatically with his line of reasoning” (Bret Stephens, as cited in Les Lynn's post, “In Praise of Disagreement”)

Les Lynn, who blogs at The Debatifier and runs Argument-Centered Education, goes so far as to say that the reason argument has gained such a bad rap in our present cultural moment is that we have “distorted debate and civil disagreement and have abandoned the conventions and norms that have made it a fundamental element of democracy and of education for thousands of years” (from “In Praise of Disagreement”).

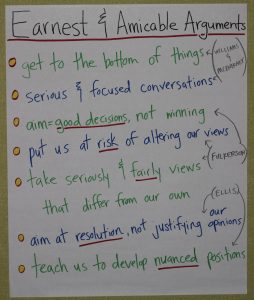

In These 6 Things: How to Focus Your Teaching on What Matters Most, I call the kind of argument described above as “earnest and amicable.”** It's earnest in the sense of intense, sincere, convicted. (Think about the “Level 5” humble-bold leaders I described a few posts ago.) And it's amicable in the sense of, “After this argument is over, we're going to shake hands, we're going to be friends.” Schools where argument permeates staff meetings and PLC sessions and PD workshops and hallway chats are schools with rich cultures. You'll find a greater share of highly engaged teachers at schools like this, and you'll find students more motivated, too. Argument like this makes us humbler, smarter, and more likely to look forward to coming to work in the morning. It gives us the sense that we're actually getting to the bottom of the big questions around schooling and the long-term flourishing of kids.

How do we do it?

In his fetchingly titled Death by Meeting, management guru Patrick Lencioni argues that the only reason so many of our meetings are “dull [is] because we eliminate the one element that is required to make any human activity interesting: conflict.” Below, I'll give you some recommendations from Lencioni's book that I think can help us get the argument train rolling in our schools.

1. Set the stakes for meetings.

Which of the following approaches is most likely to engage people in earnest and amicable argumentation?

A) “Today we need to pick what we're going to focus on this school year.”

B) “Today we need to decide on our chief focus for the school year. If we mess this up — if we're not clear, if we don't think about long-term implications — we'll end up frustrated and confused for the next nine months, and we won't move the ball forward toward the long-term flourishing of kids. If we do it right, on the other hand, we could be headed into our best year yet.”

Or:

A) “Today, team, we've got X number of kids who are showing signs that they're not transitioning well to high school. We need to identify interventions and divvy up who's going to do what.”

B) “Today we're meeting to discuss Rashad, Michael, Montelle, Izzy, and Corey. What we need to figure out is this: What's the most efficient means through which we can attempt to change trajectories for these kids? I'm not looking for any old thing we can do for them, I want to know what the smartest, most effective interventions are. We're all strapped for time — let's figure out how to do right by these kids and right by all the other ones we teach, too.”

From Lencioni's Death by Meeting, p. 228:

The key to injecting drama into a meeting lies in setting up the plot from the outset. Participants need to be jolted a little during the first ten minutes of a meeting, so that they understand and appreciate what is at stake.

(Setting the stakes is useful, too, when introducing students to today's pop-up debate.)

2. Mine for conflicts.

Nothing is more frustrating than a school culture in which arguments are ignored or discouraged. If you want to demotivate people, just make it clear that those arguers will be punished and dissenting opinions are not welcome.

From Lencioni's Death by Meeting, p. 230:

“The only thing more painful than confronting an uncomfortable topic is pretending it doesn’t exist. And I believe far more suffering is caused by failing to deal with an issue directly—and whispering about it in the hallways—than by putting it on the table and wrestling with it head on.”

So instead of ignoring disagreements, mine for them by asking “Do you agree with that?” or saying “Listen, we all know there's an elephant in the room that we don't want to discuss, and it's ______________ — lets' talk about it.”

And whenever disagreement pops up, if you're a leader, you need to say, “Yes — more of that. Keep going.”

3. But don't forget Coyle.

In an earlier post, I wrote about Dan Coyle's three skills for culture-making: psychological safety, mutual vulnerability, and shared purpose. I can't imagine a positive, argument-imbued school culture where signals of connection aren't all over the place, where vulnerability is shared and open and verbalized, where we're not constantly reminding one another, “Hey, even in the midst of this argument, this is the Everest toward which all of us strive: the long-term flourishing of kids.”

In the next post, I'll share a case study of one school in Wisconsin where informed arguments are making PD something to look forward to.

*Special thanks to Jerry Graff, whose message cohered my thinking around this post. I am thankful for your friendship, Jerry.

**Thank you to Erica Beaton, my colleague and work sister, who helped me land on this terminology.

Addendum from Marshall Memo #928: “Research shows that when it's managed well, disagreement can spur better ideas, creativity, innovation, and organizational success.”

Andrea Heard says

Dave, keep doing all that you are. I am a long time follower and reader of your blog and some of what you discuss can be used in everyday life with relationships and parenting. Hoping to see the posts that follow.