Emily was my staunch “When are we ever going to have to use this?” kid last year, especially when it came to learning map locations. We'd look at a map, and I'd ask them to identify the names of countries as a warm-up, and, without fail, her hand would shoot up to ask The Question.

“Yes, Emily?”

“Mr. Stuart, when are we ever going to use this?”

I've seen this question pop up for just about anything I've ever asked students to do — choice reading, mechanics warm-ups, whole-class complex texts, articles of the week — but until recently, I've only approached it one way: with me explaining why the thing is valuable. As I put it in the Teaching with Articles course, I think teachers have to master the apologetics of the things we want kids to do. We have to be ready and willing to provide convincing cases that, indeed Emily, knowing the names of places is worth your time and effort.

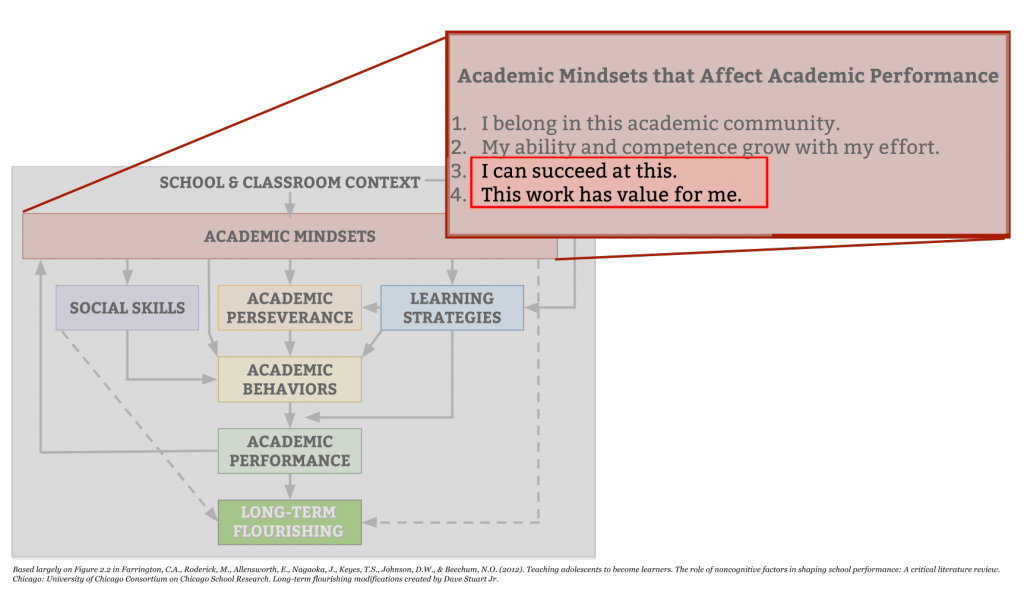

But recently, I've come across some fascinating work around an interventional approach to motivation called “expectancy-value” theory, and it's an approach that attends to two of the four academic mindsets I've been writing about lately (see Figure 1).

A Simple Expectancy-Value Activity for Helping Students Care About Your Coursework

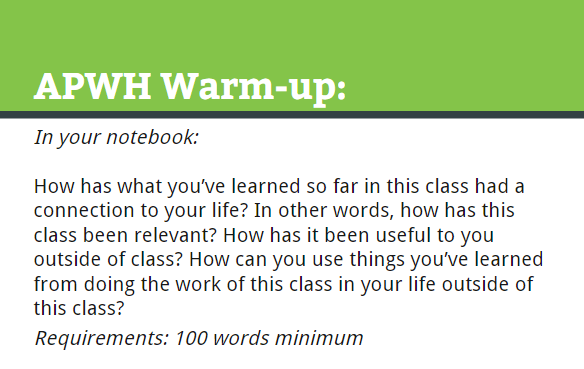

When kids walk in, I have the following warm-up slide on the screen. (See Figure 2.) The specific wording isn't critical, but what's important is that I have students reflect in writing about the usefulness of what they've learned during a given time period in my class. In other words, I'm having them do the apologetics work rather than me.

I give students five minutes for the task, pushing them as I always do to produce the 100 words. Afterwards, I have the kids do a quick Think-Pair-Share, calling on volunteers or random “index card” students during Share. This should take ten minutes maximum and can be done as infrequently as once per month.

The research base

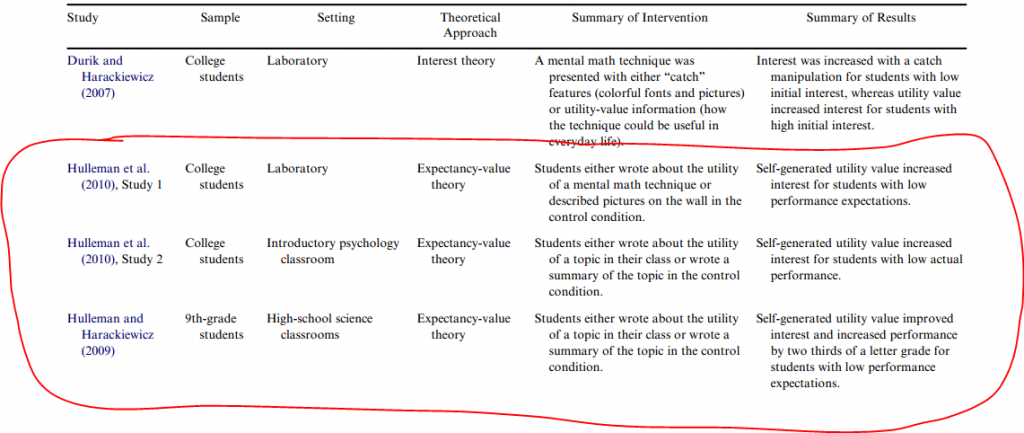

This intervention is based on three studies, all of which have Chris Hulleman's name on them. (See Figure 3. [1])

In each study, it's important to notice that the “This work has value for me” mindset increased specifically in kids who had either low expectancy of performance (i.e., kids who didn't subscribe to the “I can succeed at this” mindset) or low actual performance. In other words, the simple activity that my warm-up slide presents is likely only going to have an effect on the mindsets of kids in my class with low expectancy. Thus, we are provided with a classic example of the limitations of interventional approaches to student motivation — they tend to produce effects in only subsets of the student population.

However, since such a writing exercise would also serve the end of increasing the quantity of writing our students do and letting kids rehearse previously learned information, this task is valuable for all kids. As an additional bonus, this falls solidly in the category of provisional writing, so there's no need to micro-grade it.

In short, this activity costs us very little (about 10 minutes per month) and has an evidence-based likelihood of making a difference for a certain kind of unmotivated kid by increasing value and thereby increasing performance.

Footnote:

- See “Harnessing Values to Promote Motivation in Education,” by Judith M. Harackiewicz, Yoi Tibbetts, Elizabeth Canning, and Janet S. Hyde for the full chart.

Fatuma Hydara says

Hi Dave! I just shared in my school’s Facebook group page and it looks like the entire school will be doing this as a Do Now before our students analyze their Interim Assessment data. 🙂

Also, where can I find more information about your Academic Mindset model. It’s aligned to the efficacy which our school is utilizing this year, but I like the language of your “I” statements. Thanks!

davestuartjr says

Wow, that’s amazing! Go here (http://davestuartjr.com/four-academic-mindsets/) to find more on the Academic Mindsets, and here (http://davestuartjr.com/consortium-framework/) to find a quick overview of the Consortium Framework — both of which aren’t mine!

Kathy says

This is great, Dave! I will definitely use this strategy. Even if the greatest impact is on a “subset” of students when viewed as an intervention, I believe every student will benefit from the metacognitive aspect. Evaluating the effectiveness of one’s own actions, and the learning that impacts it through writing is powerful. This is because, even if students are determining the value of coursework itself, they will also be thinking about their own actions in relation to the coursework. It’s a win for everyone in my mind.

davestuartjr says

Me, too, Kathy — a definite, easy win 🙂