What follows is my abbreviated summary of the central structure of Camille Farrington et al.'s Teaching Adolescents to Become Learners. The report is over 80 pages long, so really, this is super abbreviated, probably past what is prudent. My hope with this post is to give you enough of a look at the Consortium Framework to realize the report is worth some professional study.[hr]

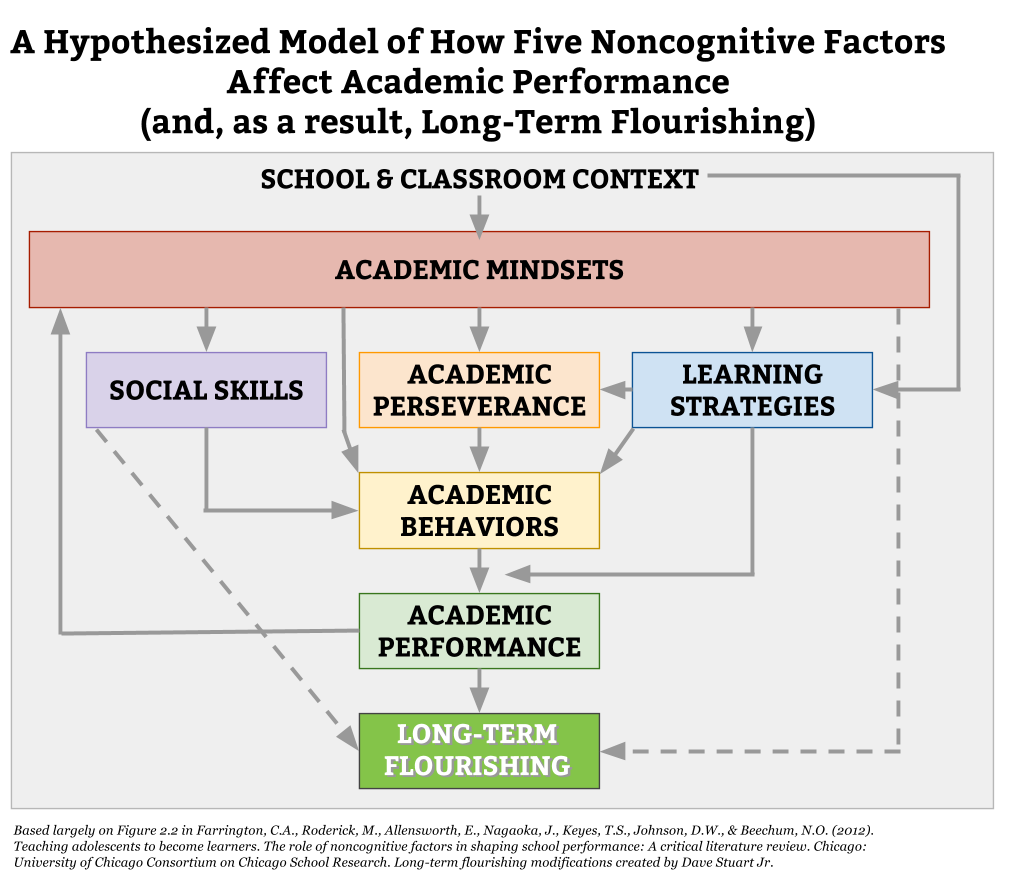

Intelligence, knowledge, and literacy (cognitive factors) affect Academic Performance through Academic Behaviors (see Figure 1): attending class, organizing materials, studying, doing homework, and participating. However, not all Academic Behaviors are created equal, as some students do these things with exceptional effort and resilience. The more effort and resilience kids put into their work, the more Academically Perseverant they are.

As tempting as it is to try to build Academic Perseverance (grit, self-control, delayed gratification) in kids, it's actually more effective to aim for their beliefs (Academic Mindsets). Specifically, we want kids to believe, at a level that affects how they operate:

- I belong in this academic community. (Belonging)

- My ability and competence can grow with my effort. (Growth Mindset)

- I can succeed at this. (Self-efficacy)

- This work has value for me. (Relevance)

Plenty of evidence suggests that these beliefs can be affected through both specific interventions and broader school/classroom contextual factors. (This is in contrast to the evidence around Academic Perseverance.) However, there is still much to be discovered about how to best affect the mindsets, meaning there is plenty of room for teachers and school leaders to work on the frontiers of this exciting research.

Importantly, Academic Mindsets seem to affect everything else in the Farrington Framework: the degree to which one completes the Academic Behaviors, the degree to which those behaviors are completed with effort (Perseverance), the degree to which one uses Learning Strategies, and the degree to which one effectively uses Social Skills. As the mindsets do their work, Academic Performance tends to increase, thus reinforcing the Mindsets and creating a flywheel effect.

If Academic Behaviors are the car, Academic Mindsets the fuel, and Academic Perseverance the horsepower, then Learning Strategies are the handling; they affect how well the Academic Behaviors work. Learning Strategies include study skills, goal-setting, self-regulation, and metacognitive strategies. Like Academic Mindsets, these seem able to be heavily influenced by both interventions (e.g., lessons in which they are explicitly taught) and contexts (e.g., classrooms and schools that do a particularly good job of making the use of learning techniques a normal, logical thing).

[box type=”tick” size=”large”]In short: we're wisest to aim our noncognitive teaching efforts at what Farrington calls Academic Mindsets and Learning Strategies. We aim at these things using a two-pronged attack: specific lessons or interventions aimed at improving these factors, and general context/culture pieces aimed at making them stick. In doing these things, we coherently address some of our perennial challenges as teachers: student motivation, student ownership, and the gap between motivation and execution.[/box]

P.S. I didn't mention Social Skills in this summary because, while Social Skills certainly seem likely to influence Long-Term Flourishing, there isn't a ton of research closely linking them to Academic Performance.

[hr]Thank you to Camille Farrington, Melissa Roderick, Elaine Allensworth, Jenny Nagaoka, Tasha Seneca Keyes, David W. Johnson, and Nicole O. Beechum of the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research. Their report has clarified a great deal for me. Also, thank you to Paul Tough, whose Helping Children Succeed was the first to point me toward the Consortium's work.

Kathryn Haugrud says

So where do we get quality, research-based lessons and interventions that improve the noncognitive factors? Any recommendations? And, how do we fit those into our standards based curriculums?

davestuartjr says

The report ends saying that this is still very much a need. At this point, Kathryn, we have to create them from an understanding of the research. A collection of some of my lessons is included in the Pay Whatever You Want Student Motivation Starter Kit: https://gumroad.com/l/noncognitive

The standards aren’t going to include noncogs — nor is standards-based grading. That is an unfortunate limitation of these things.